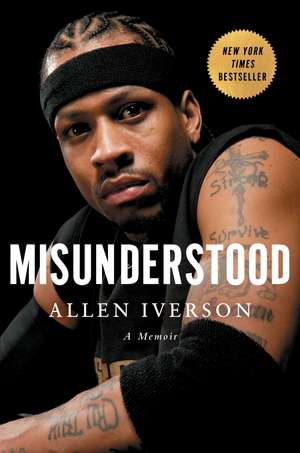

Misunderstood: A Memoir

Autor Allen Iverson Cu Ray Beauchampen Limba Engleză Hardback – 4 dec 2025

A compelling and candid memoir from Allen Iverson, the NBA’s most misunderstood Hall of Famer, detailing his tough childhood in Virginia, his entry into the league as the number one overall pick, and his controversial, culture-changing pro basketball career.

In Misunderstood, Allen Iverson shares in searing clarity and touching candor his meteoric rise from impoverished child in the Virginia projects to high school champion to Georgetown University protégé of legendary coach John Thompson, and finally to NBA All-Star and Reebok’s Vice President of Basketball.

Allen Iverson is a household name—Boomers and Gen Xers watched his decades-long run as a scrappy, tenacious basketball player on the Philadelphia 76ers who redefined the sport’s style (both fashion-wise and playing-wise), while millennials and Gen Zers are perhaps more familiar with his Reebok line’s resurgence in popularity, his callout in Post Malone’s viral hit “White Iverson,” and for being the namesake of Kendall Roy’s son on Succession. Part athletic legend, part fashion icon, part hip-hop muse, Iverson was one of the first celebrities to fuse lifestyle, culture, and sports.

But while everyone may know his name, few have seen behind the curtain on Iverson’s tumultuous life. Misunderstood lifts the veil and brings you into the mind of the pugnacious, ultra-talented misfit whose foremost goal, more than fame or fortune, was always to lift his family and friends out of poverty and violence. In his memoir, Iverson explores how he completely shattered the mold dictating what an NBA star could be in the 1990s and 2000s, all while dealing with legal troubles and personal traumas that only contributed to his sense of individualism and star power. This is the unforgettable story of a trailblazer who not only changed the game of basketball but rewrote the rules of what it means to rise, fall, and rise again while staying unapologetically true to himself.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 61.26 lei Precomandă | |

| Gallery/13A – 22 oct 2026 | 61.26 lei Precomandă | |

| Hardback (1) | 111.91 lei 21-33 zile | +49.77 lei 6-12 zile |

| Gallery/13A – 4 dec 2025 | 111.91 lei 21-33 zile | +49.77 lei 6-12 zile |

Preț: 111.91 lei

Preț vechi: 138.58 lei

-19% Recomandat

19.79€ • 22.97$ • 17.09£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 03-15 aprilie

Livrare express 19-25 martie pentru 59.76 lei

Specificații

ISBN-10: 1476784396

Pagini: 352

Ilustrații: 1-c stocked endpapers

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.52 kg

Editura: Gallery/13A

Colecția Gallery/13A

Notă biografică

Allen Iverson played for fourteen seasons in the NBA, during which he was Rookie of the Year, MVP, and eleven-time All Star. He was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2016. In 2021, Iverson was selected to be part of the “NBA 75,” a group of the seventy-five most important players in the league’s first seventy-five years, thus cementing his status as one of the sport’s best players. Know equally for his aggressive, fast play style and groundbreaking integration of fashion and self-expression into sports, Iverson helped to usher in the age of hyper-individualistic sports personalities and shaped American culture in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Iverson has had a career-long partnership with Reebok, for whom he now serves as Vice President of Basketball.

Ray Beauchamp has been a criminal defense attorney in New York for the last fifteen years, having advocated for the rights of indigent people at the Legal Aid Society in Manhattan and the Bronx. Prior to Legal Aid, he clerked in the Second Circuit and served as managing editor of the Fordham Law Review. And prior to all that, he was a kid in West Philly, developing and nurturing a deep love of the 76ers.

Recenzii

—Kirkus

Descriere

A compelling and candid memoir from Allen Iverson, the NBA’s most misunderstood Hall of Famer, detailing his tough childhood in Virginia, his entry into the league as the number one overall pick, and his controversial, culture-changing pro basketball career.

Extras

ONE NANA AND MOM

I was born on June 7, 1975, in Hampton, Virginia. My mom, Ann Iverson, was fifteen. My biological father was in Hartford, Connecticut. And from the beginning, my family didn’t have much.

I grew up on “The Peninsula,” with the Chesapeake Bay on one side and the James River running along the other. Hampton and Newport News are like sister cities there. I lived in both at different times. Really, I can say I grew up in both places. I was a Newport News dude, but I also grew up in Hampton.

But before I get to that, the story really begins in 1971 in Hartford. That’s where my mother had been raised. By then, just twelve years old, she had three younger siblings: Jessie, Steve, and Greg. Her mother—my maternal grandmother—was thirty, raising the four of them by herself. She didn’t want more kids, so she got her tubes tied. When she got home from the procedure, she wasn’t feeling well, and after a while couldn’t even stand straight. My twelve-year-old mom was on the phone with a sheet over her head to keep out the background noise—small house and lots of kids running around—when my Aunt Jessie interrupted her to say their mom didn’t look right. They called an ambulance to come get her. My mom wanted to go to the hospital, but the last words her mother said to her were “No, you watch Jessie and Stevie and Greggy for me.” Her mother never came home. It was an infection from the surgery. My mom could tell you to the penny how much the hospital gave as compensation: $3,818.18.

“Don’t forget the eighteen cents,” she would say.

My mom and her siblings were now motherless, but they were blessed to have a saint of a grandmother (my great-grandmother), whose name was Ethel Mitchell—“Nana” to all of us. Nana agreed to raise those four grandkids. Story goes that Nana’s husband had enough with raising kids. So Nana was on her own.

After a couple of years, Nana started thinking about a change. My teenage mom was playing basketball then. (She said she had her coach telling her to “slow down and pass the ball.” Sounds familiar.) She was also finding trouble—thirty-eight fights, she counted. After the last one, Nana was done. The family had moved to Connecticut years before, but she was originally from Virginia and still had family there. Once she saw a future raising those four grandchildren, and looked out her window at a Hartford neighborhood she didn’t really like anyway, she decided to move back home. And maybe it had something to do with me too.

See, 1974 came, and Nana had already been taking care of my mom and the others for a little while. My mom was fifteen by then. She had been dating Allen Broughton for a couple years. Broughton was a star basketball player, just one year older than my mom. (He was only 5'5", but they said he played bigger than his size. Also sounds familiar.) All I know is that by the time the family moved to Virginia, my mom was pregnant. They made it to Virginia in time to enroll her into high school—at Bethel, where I’d end up winning a few games. That January, she ran the point, five months pregnant with me. Of course, I don’t remember that!

So as I said, I was born June 7 of that year, 1975. When I was born, my mom says she knew after taking just one look at me—she saw my long arms and immediately said I’d be a basketball player. She just knew. And whatever anyone can say about my mom, she believed in me that day, and every day after that. I only made it where I made it because of her. Because of her belief in me.

Not long after I was born, I got the name everyone called me. You may know me by “AI” or “the Answer,” but all that came later. Everyone in the family was trying to come up with a nickname for my baby self—“What are we going to call Allen?”—because in my family your name wasn’t necessarily what you got called. For instance, my mom was “Juicy,” and her sister was “Lil Bit.” That’s just how it was. So story goes that two uncles up in Connecticut were arguing over what my nickname would be. One uncle was called Bubba and the other was Chuck. Well, they got to arguing that I should get one of their nicknames as my own, and my mom said, “You know what, you both can be right. Bubbachuck.” And so that’s what it was from that day forward. Everybody called me Bubbachuck, sometimes just “Bubba,” or mostly just “Chuck.” You watch my games from when I was a kid, even the announcers called me that. And to this day, among my family, my friends, and when I go home, it’s “Bubbachuck.”

My first memories are from living with Nana on Jordan Drive in Hampton, in the Aberdeen section of town. She had a little one-story house with vinyl siding, set back from a creek. I don’t remember it all of course, those early years. But I do remember it being crowded. It’s hard to say how many of us there were. It had two bedrooms. We made room for ten or twelve people depending on the time. There was Nana; there was my mom; her little sister, Jessie; her two brothers, Stevie and Greg; and then me, of course. Others came and went. We didn’t have a lot of money either. Now, that ain’t no excuse for anything. It’s just how it was. Mom was still a kid then. Looking back, I can see that. So I was raised by the whole family.

Those first couple years after I was born, my mom kept playing basketball. She was the point guard her junior and senior years in high school. Then she graduated from Bethel High—something I never got a chance to do after they threw me in jail.

My mom was still a kid, so it was Nana who managed the house. She was the parent to all of us—obviously to my mom and her siblings, but also to me. She was just the backbone of the family, but it was hard trying to be the person that wants to and has to do everything, but you just don’t have the finances, you don’t have everything to be able to do it. The best way she could, she did. Everybody in the family respected her and looked up to her. She had strict rules, as a churchgoing, God-fearing woman. So we weren’t playing music in the house. We had to keep it clean. People had to be home at a certain time. And everyone came to her to sort their shit out. Because she just had the ability to break things down and make sure everything was handled the way it was supposed to be. In her life, she had three kids. My grandmother, you know about, how she passed after going to the hospital. But for Nana, all three of her kids died before she did. So my mom, and Aunt Jessie and Uncles Steve and Greg, they were like her kids. And then there was me. I was the youngest, so Nana spent a lot of time looking after me, making sure I got dressed, got fed. She really took care of everyone, but me being the youngest, we had a special bond. I was her baby.

Back then she drove a big old burgundy car from the 1970s. I wish I could remember what it was. But I do remember that it had a big door handle that came in from the side far enough that when I was real little, I could sit on it kind of sideways. Kick my feet up on the seat. I don’t know why, but that was just the way I liked to sit. Nana would be like, “Get off that door before you fall off this car.” I would for a second, but then seconds later I used to get back on it. Well, one day I was in the car with her and my cousin, sitting like that. We were on the interstate. There was traffic, so we were hardly moving. Sure enough, the damn door popped open. Out I fell right onto the highway. My cousin grabbed me up quick and got me in the car. Thank God for the traffic jam. I started crying like a baby. Nana was so worried I might have done something really bad. But my cousin was like, “Aw, he just crying ’cause he scared.” I never sat on the door handle like that again.

Nana watched me close. And we just got along so well. It’s hard to explain, but we had the kind of relationship that when I was away from her, I would just look forward to being with her again. You know when you first get with a girl? All you want to do is see her all day? That’s how it was. Like when I was on the bus coming home. Just looking forward to seeing her. To spend time with her, sit up under her. When we were together, she would take me wherever she had to go, in that burgundy car—to the store, to see family, everywhere.

Family time for me wasn’t like it is today. When my kids were smaller, I would take them to Great Wolf Lodge or something and when we were in the car to go home, they’d ask, When are we coming back? That’s the way I like it, I guess. I want them to have what I never had—a stable family life, presents under the tree, you know, nice shit. But it wasn’t like that for me. Now, that didn’t mean I wasn’t having fun and being loved. It was just that I followed my family’s schedule if I was with them. So when I spent time with Nana, it was going wherever she was going, to the store, to church, wherever.

(The funny thing is Nana was out having fun. I just didn’t know it. I found out years later that she drove that car of hers from Hampton to Atlantic City a lot of those weekends of my childhood. She’d drive up there, play whatever games she played, and be back before I noticed. That’s a six-hour drive!)

In those days, I had a lot of energy. When you’re a kid, all you want is to be outside. I mean, there wasn’t anything to do inside. Again, it wasn’t like it is today, where kids have videogames and all that, big-screen TVs, and any damn show they want. For me it wasn’t like that. The one thing I would do inside is draw. If it was raining outside, or I was stuck in the classroom. I would draw all kinds of shit. What I would see or learn, I would re-create it. Teachers and adults would look at my artwork, and they’d be like, Son, you got a future. I loved doing it, and I loved the recognition. But for the most part, inside was boring.

So I would go outside. Nana’s house in Aberdeen was right on that little creek, and I’d go down there to catch crawfish and to play in the water. It’d be fun down there, but it made Nana a little nervous, I think, especially when she wasn’t around. We had such a good relationship, so much love, so that’s why I remember the one time she laid her hands on me. I must have been four or five years old at most. She was going to church. So she said to me, “Now Chuck, don’t go down to the creek while I’m gone. You stay in the house.”

I nodded like, Yeah no problem. But I had no intention of staying in the house that whole time. I watched her drive the car away, down the block. Didn’t wait more than a second after she got out of sight. I went out the back door right back down to the creek. Well, I guess she had a hunch. Because a few minutes later I looked up and saw her staring down at me. My heart just sank, man. I didn’t want to let Nana down. So she gave it to me good.

It wasn’t a feeling I ever wanted again—to let her down. And like I said, that was the only time that she ever put her hands on me. Nana was someone I wanted to do right by. She was the person I wanted most to make proud. That’s why I remember that day so well, and I never disobeyed her like that again. It’s something I think so much about, because she saw me go to jail, but she never saw me play in the NBA.

For the most part as a kid, I was allowed to go outside and do what I wanted. As soon as God opened my eyes in the morning, the first thing I’d do was hop up and go outside. I had Stevie and Greg, my two uncles, to push me around. Those two guys were everything to me. I looked up to them because they were out there doing all the things I wanted to do eventually—playing football, number one. Stevie was the younger one, and he was close to Nana as well. He was the closest to her of the four kids. Nana loved him. And he was the one who took care of her when she was dying. I don’t want to even think about those days. They came much later.

Stevie and Greg both played football at Bethel. They were good but weren’t pros or anything. I liked watching them. Then as soon as I could run, I demanded to play with them. They could see my quickness. Just give me the football. I’d take it and just go, freedom in running wild among the older dudes—we’d see if any of them could knock me down. Of course they could. They would tackle my ass again and again. Didn’t matter how many times. I just said, “Let’s do it again,” because I wanted to do it until they couldn’t fuck with me anymore, until I beat their asses. That was something I always did: just kept going until I could win.

One game we played was called hot ball. That’s where you throw it up, one guy catches it, and everyone tries to tackle him before the guy can get to the end zone. I played that game hundreds of times—at my Nana’s and later when we moved to Newport News. I got so damn good at it, I was dreaming of a future in professional sports.

I’d reach that dream eventually, but when I was little I almost lost the chance. I was at the bus stop, in the fourth grade. It was raining. And you know how when you’re little, you want to be at the back of the bus? That way you’re farther away from the bus driver, so you can act up? Well, the way to get the seat in the back was to be the first in line to get on the bus. No one was going to stop me from being in the back of that damn school bus.

So I was standing there as the bus pulled up. Someone from behind pushed me a little, like jostled me, and I slipped. My foot went into the street, and the bus ran right on over it. In fact the wheel was on top of my foot as the bus came to a stop. The other kids in the line started screaming at the bus driver, “Ms. Barrett, you just drove over his foot!” but she was just saying, “What?” She couldn’t hear, and for some reason she wasn’t opening the door. She finally came to realize that the bus was on my motherfucking ankle. She put the bus in drive and rolled on up over and off of it.

What I did then was I just stood up to get on the bus. I was going to be first on that bus. Nothing was going to stop me. Ms. Barrett was like, “No, you can’t get on here.” She looked scared. Then I sat back on the ground and realized what was happening. My ankle was all bent up. I was in shock, I guess. And then everything cut out. I don’t remember the ambulance, though it came. The next thing I remember I was in bed.

My ankle was broken bad. I was crying, and I told Nana I didn’t think I would be able to play sports anymore. She just said, “It’s all right, it could have been your chest or your head. You could be dead.” She wasn’t going to let me have a sympathy party. And she was right. So I decided it wasn’t going to stop me. I could recover. Later, I had to have a checkup with a different doctor when I was still wearing the cast. My ankle was already healing some, and I was feeling a lot better. The doctor sat me down and gave me a Snickers. He said, “Tell me the truth. There is no way your ankle could have gotten ran over by a bus. It would be crushed. You’re in the fourth grade, man. That little-ass ankle.” I told him it happened. He just shook his head. I’m not sure he believed me. But it sure made me feel better that it was healing.

Things were looking up. When I got back to school I did get my sympathy party. I took full advantage. When we had to line up, I went to the front of the line, like at the cafeteria. People were signing my cast. And before long my ankle was healed well enough that I was back at it. It didn’t stop me from playing football a month later. I came back better than ever, glad I’d survived fourth grade.

My mom would watch me play football sometimes, and she’d smile. I think she knew it was basketball that I would play. I mean, she said it when I was born. But she’d watch me run through her brothers and a lot of the older kids, and she just could see that I had talent.

With my mom and me, even early on, sometimes it felt like we were friends, or brother and sister, as much as she was my mom. I don’t mean that in any kind of way. I just mean that she was so young that we would just have fun together, whether it was listening to music, or sharing our love for jewelry, imagining the gold, the diamonds, the sparkle, the bling. In a way, we grew up together.

But she struggled to do all the things most other parents do, like pay the bills. A lot of bills didn’t get paid. She had so many jobs. She worked as a forklift driver in the Avon warehouse and as a cashier at a supermarket. She worked as a typist at Langley Air Force Base. And she even worked at the shipyard, the big spot in the Peninsula. That’s where a lot of people could get real jobs that paid all right. But she was out of work as often as not, and we didn’t have much. She once put it like this: “I’m trying to keep a roof over their heads and mine. Tight isn’t the word for our money. If there’s another word past tight, use it.” To get shoes for me as a youngster, she’d take me to the store. We’d walk up to the display, where they had all the shoe boxes on top of one another, and she’d be like, Try these on. Once she saw they fit, she’d tell me to walk on out of there with them. I hated that shit. I wanted to get shoes the regular way!

Before I have any memories, like when I was an infant, my mom met Michael Freeman. He became my dad. I didn’t have a life without one. That’s not my story. I mentioned Allen Broughton—well, evidently that was my biological father, but I never met him in person.

Michael Freeman was doing all right when he met my mom. He was working a real job in the shipyard. He was a small dude and went by the name “House Mouse.” He could play basketball himself. A Sixers fan, his favorite player was Mo Cheeks. Maybe that was why it was meant to be, me going to the Sixers.

Unlike my mom, my dad never laid his hands on me. His way of putting down the law was just like a look. A look to tell me, that wasn’t right, whatever I was doing. Once he got involved with my mom, he really was the one to take care of things when he could.

When I was about four, my mom got pregnant with my sister, Brandy. At that point, I think my mom was probably ready to move out of her grandma’s house. We all loved Nana obviously, but I think my mom wanted her freedom. Nana had her rules, being home at a certain time, not listening to music too loud or too late, allowing only some friends over. My mom wanted to live by her own rules. And I guess you could say maybe I got that from her. She also never liked taking criticism, even if it was constructive. Now that she was going to have another child, this one with my dad, it just made sense to move in with him.

So we moved into a two-bedroom in the Pine Chapel apartments, which was still in Hampton but nearer to the Newport News line. I can’t remember too much about that place, but I can remember my white sheets and the green curtains. I can’t remember things like even Brandy’s first day back from the hospital, but I can remember the color of the curtains and the sheets. The random shit I remember—it’s strange.

I think my mom was glad to have her freedom. Now she could smoke cigarettes if she wanted to, and she could play music. She had a brown clock radio and she’d blast music through the apartment all the time, every day. It didn’t have a record player, or anything fancy like that. The music we listened to back then was soul, R&B, all that stuff. It was something new for us, and it just floated through the house all the time.

It was around then that we began to listen to Michael Jackson. Man, I loved his music so much. It’s something my mom and I shared, and as I was growing up each new song would come out, and it would be the most exciting thing. Everyone knew that about me—obsessed with Michael Jackson. Later in life, I would sing “Man in the Mirror” on the bus after games, teammates getting sick of that shit. But I’d just raise the volume.

I remember years later, I was playing in Denver. I was on the training table and I had my headphones on, and Carmelo Anthony came in. He took one look and told some of the other guys, “You don’t even have to ask what AI is listening to. All he listens to is Michael Jackson. He loves that man!” Everyone cracked up because they knew he was right. That all started with me and my mom—like everything else.

When we were in Pine Chapel, I used to cry and ask for my Nana. But Mommy was like, “Your Nana ain’t here. You living with me now, and I don’t wanna hear that shit.” I still got to visit Nana, but it wasn’t the same. My mom probably was focusing on the baby. And my dad was around, but it wasn’t like it was smooth. It was never normal. Him and my mom, they always had their things. So we all moved in together, but he was sometimes there, sometimes not.

One night, some fucked-up shit went down. My parents were in the “off” part of the “on-off” cycle, and my mom had a dude over from across the street. The two of them were talking and whatnot when my dad came by. Voices got raised. Me and Brandy were in our room, just being quiet—she was still a little baby. But I could hear the argument.

I heard it escalating, so I went out of my room and looked in the kitchen, where my dad and the neighbor were standing chest to chest. Then it came to fists getting thrown, and I scrambled back to my room. Seconds later, I heard the gun go off. I came back, and my dad had hit the man with a gun, and evidently it discharged. The dude was on the ground. It looked like half his head was gone, man. Blood everywhere. That’s what I remember. The blood pooling on the floorboards. That color of red sticks with me like the white sheets and green curtains. I ran back to my room again to get away, to put that image out my head. Fucked-up. But I had to learn right then, at that moment, that it was just a fact of life, that you can’t stop and dwell. As a kid, I’d cry every time my team lost a game. But for this kind of shit, I had to not think about it, not talk about it, definitely couldn’t cry about it. Thank God my kids haven’t had to experience shit like that.

The police ended up coming around and they picked Daddy up. The dude was hurt but he didn’t die. It was self-defense, so my dad wasn’t locked up for long.

After that, the family was ready to move again. Mom found a new place, over in Newport News, in a project called Stuart Gardens.

It wasn’t the most stable situation, but my mom was there for me. I remember I was talking to her one time when I was still little. I said to her, “Mommy, you think I could play in the NBA or NFL?” I was just a kid. I hadn’t even won a trophy yet.

She looked at me and said, “I know you can. You’re going to do it.”

I actually believed it. So I would tell the other kids about my plans. When everybody was laughing at me and my dreams, I used to basically say to them, “You laugh all you want, but my momma told me I could.” Like that was the gospel, man. My mom told me this, so you can laugh all you want.

To this day, I will never forget her saying that. She believed in me totally. That meant everything to me, even if it wasn’t perfect all the time.