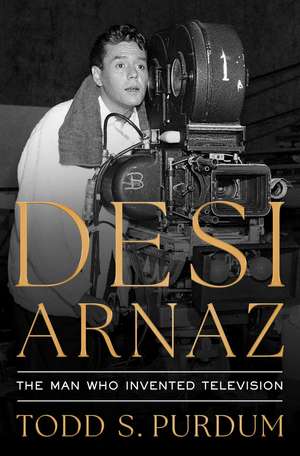

Desi Arnaz: The Man Who Invented Television

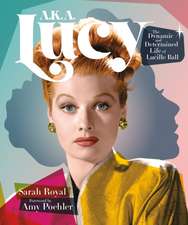

Autor Todd S Purdumen Limba Engleză Hardback – 3 iul 2025

Desi Arnaz is a name that resonates with fans of classic television, but few understand the depth of his contributions to the entertainment industry. In Desi Arnaz, Todd S. Purdum offers a captivating biography that dives into the groundbreaking Latino artist and businessman known to millions as Ricky Ricardo from I Love Lucy. Beyond his iconic role, Arnaz was a pioneering entrepreneur who fundamentally transformed the television landscape.

His journey from Cuban aristocracy to world-class entertainer is remarkable. After losing everything during the 1933 Cuban revolution, Arnaz reinvented himself in pre-World War II Miami, tapping into the rising demand for Latin music. By twenty, he had formed his own band and sparked the conga dance craze in America. Behind the scenes, he revolutionized television production by filming I Love Lucy before a live studio audience with synchronized cameras, a model that remains a sitcom gold standard today.

Despite being underestimated due to his accent and origins, Arnaz’s legacy is monumental. Purdum’s biography, enriched with unpublished materials and interviews, reveals the man behind the legend and highlights his enduring contributions to pop culture and television. This book is a must-read biography about innovation, resilience and the relentless drive of a man who changed TV forever.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 62.02 lei Precomandă | |

| Simon&Schuster – 2 iul 2026 | 62.02 lei Precomandă | |

| Hardback (2) | 107.53 lei 26-38 zile | |

| Simon&Schuster – 3 iul 2025 | 107.53 lei 26-38 zile | |

| Thorndike Press, a Cengage Group – 28 ian 2026 | 281.48 lei 22-36 zile |

Preț: 107.53 lei

Preț vechi: 139.13 lei

-23%

Puncte Express: 161

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.00€ • 22.36$ • 16.59£

19.00€ • 22.36$ • 16.59£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 20 martie-01 aprilie

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781668023068

ISBN-10: 1668023067

Pagini: 368

Ilustrații: 16-pg b-w insert

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1668023067

Pagini: 368

Ilustrații: 16-pg b-w insert

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Todd S. Purdum is a veteran journalist and author. In a career of more than forty years, he has written widely about politics and culture, starting at The New York Times, where he spent twenty-three years, covering politics from city hall to the White House, later serving as diplomatic correspondent and Los Angeles bureau chief. He has also been a staff writer at Vanity Fair, Politico, and The Atlantic. He is the author of Something Wonderful: Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Broadway Revolution and An Idea Whose Time Has Come: Two Presidents, Two Parties, and the Battle for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife, the former White House press secretary Dee Dee Myers, with whom he has two grown children.

Extras

ProloguePROLOGUE

On Sunday evening, October 3, 1954, Ed Sullivan, the stone-faced New York newspaper columnist who had become perhaps the most awkward, unexpected television star, hosted a special celebration on his popular CBS program, Toast of the Town: a tribute to I Love Lucy, the network’s top-rated show, which was already a national institution on the eve of its fourth season on the air.

At a V-shaped banquet table bedecked with flowers, Sullivan had assembled a collection of celebrities—including Dusty Rhodes, the New York Giants outfielder who had just led his team to a World Series victory, and Howard Dietz, the lyricist of Broadway standards like “Dancing in the Dark” and “You and the Night and the Music”—to pay homage to the most beloved husband-and-wife team in contemporary entertainment, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz.

The evening’s roastmaster was a balding, avuncular, tuxedoed character named Tex O’Rourke, a onetime Texas Ranger, Wild West show performer, sports promoter, and boxing trainer who introduced Lucy and Desi as “two of my very favorite people, who have virtually dynamited their way into the hearts of all of us.” By this point, Lucille Ball needed no introduction to anyone, but O’Rourke nonetheless fancifully celebrated her as “the worst kind of redhead.” O’Rourke then turned to Arnaz, who was in fact the dominant force behind the scenes of I Love Lucy. “Down in the Caribbean, another hurricane was making up” one who “was born with a golden guitar in his lap, son of the alcalde of Santiago de Cuba, the biggest mansion in town, the biggest ranch in the hills, imported motor cars, a yacht.” Then came the revolution of 1933. “He was lucky to get out of the country, got over into Miami, a refugee, penniless… He hooked up with a fella who supplied canaries for the local drugstore.” At this, Arnaz covered his eyes in mock chagrin and demanded, “How did you find that out?” O’Rourke plowed on, “That’s my job, Desi. You might say he started at the bottom because his principal job was going around in the mornings and cleaning the birdcages. But in a way it was musical. They were singing canaries.”

O’Rourke then recounted Arnaz’s breakout as a Latin bandleader and how he and Lucy had met when Desi went to Hollywood to repeat his role as a South American football star in the film version of the Rodgers and Hart Broadway musical Too Many Girls. “From the start, it was a team through rough seas and smiling skies, but always a team,” O’Rourke said. “Sometimes a little bit hectic, but way down deep in their hearts they were always the kind of lovers that the whole world has got to love.”

When it was her turn to speak, Ball saved her warmest words for the man who, she knew better than anyone, had been most responsible for the show’s creation and for making her into one of the most famous women in the world. She and Desi had undertaken I Love Lucy at the lowest moment in their careers, when both had run out their string in the movies and were willing to leap into the still-untested, second-tier medium of television. Desi had persuaded a reluctant network and skeptical sponsor that the public would accept them—an unconventional, intermarried couple—as an all-American team. He had seen something in Lucy—and in the two of them together—that he knew would click with audiences. In personal terms, the show was also a determined attempt to save their marriage, after ten years of frequent career conflicts that kept Desi on the road with his band, by allowing them to work together at last. Now they had triumphed beyond their wildest expectations and seemed to have everything.

“His name escapes me at the moment,” Ball deadpanned, “but this guy, who seems to be in all places at once, making like an actor, a banker, a politician—in short, a producer—gets my vote as the greatest producer of all time. And I have two little Arnazes at home to prove it.” At this she cast a sexy, heavy-lidded sidelong glance at her husband, the studio audience burst into supportive laughter, and Arnaz wiped his forehead with his pocket square. “Desi, I love you,” she said. “Signed, Lucy.”

Arnaz rose last, with an earnest intensity not at all like his character Ricky Ricardo’s so-often-exasperated mien. “Thank you, sweetheart,” he began. “Thank you, Ed. You know, if it wouldn’t have been for Lucy, I would have stopped trying a long time ago, because I was always the guy that didn’t fit.” He recounted his uphill battle to get the show on the air with himself as the costar. “Finally, one executive at CBS said, ‘Well, maybe the audience would buy him, because after all they have been married…’?” Struggling to compose himself—his shoulders hunched, looking into the middle distance and not at the camera, barely holding back tears—he went on. “We came to this country, and we didn’t have a cent in our pockets. From cleaning canary cages to this night here in New York is a long ways. And I don’t think there’s any other country in the world that could give you that opportunity. I want to say thank you. Thank you, America. Thank you.”

Arnaz sat down with his head in his hands. Sullivan—a keen judge of talent who had known Desi for years and understood better than most the crucial role he had played in his wife’s success—cuffed him around the ear and drew him close in a fatherly embrace.

The gratitude that Desi Arnaz expressed that night was mutual, for against all the odds, white-bread, conformist, Eisenhower-era America had taken him and his unconventional alter ego to heart. He was adored as the man who loved Lucy, the combustible Cuban bandleader whose spluttering Spanish and long-suffering straight man’s frustration at the comic antics of his crazy wife softened into a loving embrace at the end of each episode. But Desi Arnaz was so much more than Ricky Ricardo. If Ball’s brilliant clowning—her beauty, her mimicry, her flexible face and fearless skill at physical comedy—was the artistic spark that animated I Love Lucy, Arnaz’s pioneering show-business acumen was the essential driving force behind it. He was, as NPR’s Planet Money once put it, the man who “invented television.”

“There’s a misconception that we—that Desi wasn’t all that important to the show,” Madelyn Pugh Davis, the founding cowriter of I Love Lucy, would recall years after his death. “And Desi was what made the show go. And he also knew that she was the tremendous talent. He knew that. But he was the driving force, and he was the one who held it together. People don’t seem to realize that.”

Today, nearly four decades after his death, Arnaz the performer remains a widely recognizable figure—“one of the great personalities of all time,” as his friend the dancer Ann Miller once put it. Much less well understood is the seminal role he played in the nascent years of television, helping to transform its production methods, and transforming himself, a successful but second-tier Latin bandleader, and his wife, a journeyman actress in mostly forgettable B movies, into cultural icons.

It was Arnaz (and I Love Lucy’s head writer and producer, Jess Oppenheimer) who assembled the world-class team of Hollywood technicians who figured out how to light and film the show in front of a live studio audience, with three cameras in sync at once—a then-pathbreaking method that soon became an industry standard for situation comedies that endures to this day. It was his ability to preserve those episodes on crystalline black-and-white 35-millimeter film stock that led to the invention of the rerun and later to the syndication of long-running series to secondary markets. This innovation also made it possible for the center of network television production to move from New York to Los Angeles and created the business model that lasted unchallenged for the better part of seven decades, until the streaming era established a competing paradigm.

“I Love Lucy was a crucial part of entertainment in this country,” said Norman Lear, the creator of the landmark situation comedy All in the Family and many other shows. “Lucy and Desi—I think it can be said they pretty much opened the door of Hollywood to America, and to the situation comedy. There was only one Lucy and one Desi, and between them, they knew what it took. He was a great businessman in the persona of a wonderful entertainer.”

It was Arnaz’s unselfconscious portrayal of the paterfamilias of an ethnically mixed family that proved a vivid contrast to the all-WASP lineup of contemporary sitcoms like Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver, and made him a breakthrough cultural figure in a country that would soon be transformed by growing social justice activism and a greater acceptance of diversity as a strength.

“In real life or fiction, neither Desi nor Ricky ever betrayed his Latino identity,” the columnist Miguel Perez would write in the New York Daily News after Arnaz’s death. “When Americans saw him on the screen in the 1950s, and when the world sees him now and in the future, they will not see Arnaz playing one of those criminal or drug-dealer roles usually given to Latinos. They see him as the head of an American family who, in spite of his accent and Cuban quirks, is realizing the Latino-American dream.”

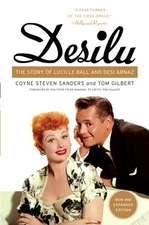

Finally, it was Arnaz whose name came first in Desilu, the production company that he and Ball founded, which became the largest producer of television content in the world in the late 1950s; provided the studio space where many other shows, including those of Danny Thomas and Dick Van Dyke, were staged; and eventually spawned the global entertainment juggernauts Mission: Impossible and Star Trek.

From the start, Desi Arnaz’s story is that of an unrelenting go-getter who repeatedly defied conventional expectations and saw creative ways forward when others did not. He was born a son of the Cuban aristocracy, but his family lost everything and was forced to flee in the 1933 Cuban revolution that followed the overthrow of the repressive American-backed regime of Gerardo Machado. Arnaz, seventeen years old, wound up penniless in Florida. A future that had once envisioned college at Notre Dame and then a law degree disappeared in favor of a high school diploma and reinvention as a self-taught musician in Miami Beach. Eventually, he formed his own band and helped fuel the demand for Latin music that was sweeping the country, promoting the conga dance craze, first in Miami and then as a nightclub headliner in New York.

Arnaz often attributed his willingness to take risks to this youthful dispossession and trauma. The painful corollary was that even at the peak of his fame and success, he would never quite fit comfortably in either the mainstream white culture or the Mexican American community that predominated in his adopted hometown of Los Angeles. He was a refugee, not an immigrant, and he never forgot it. “If you feel betrayed by your own country, you’re always on the run,” observed the Cuban American playwright Eduardo Machado, himself a childhood refugee, from Fidel Castro’s Cuba. “And no matter how talented you are, and no matter how many things you get, you’re always being told, ‘This isn’t real. Our real life is in Cuba.’?” He added, “You feel like a phony, because you don’t know who you are. I think the more you make it, the more you feel like a phony.” Even in complimenting Arnaz’s business prowess, Hollywood resorted to crude stereotypes. “Yes, he’s the wetback they all waited for, the wetback TV was created for,” the Oscar-winning lyricist Sammy Cahn wrote for a parody roast of Arnaz to the tune of “That Old Black Magic.”

Arnaz endured endless slights from an entertainment establishment that looked askance at his accent, his ethnicity, and his perpetual public image as a second banana to his superstar wife. Too many valet parking attendants and hotel clerks addressed him as “Mr. Ball.” Well into the 1970s, newspapers and magazines routinely reproduced his spoken words in interviews in comically accented dialect, as if he actually were Ricky Ricardo. Network executives at first underestimated him, but they did so at their peril, because his explosive negotiating style often won out in the end. At the peak of Arnaz’s power, in the late 1950s, his longtime secretary Johnny Aitchison recalled that an important business caller once complained, “?‘My God, I can get to the president easier than I can get to Desi Arnaz,’ and I said, ‘Yeah, but he’s not doing a show every week, too.’?”

Arnaz himself made fun of his mangled pronunciation—“He spoke no known language,” his friend George Schlatter said—and his accent was almost as thick in real life as it was on the air. He proudly kept a sign in his house proclaiming ENGLISH BROKEN HERE. He was prone to malapropisms like “goosepimple pie,” and once in a game of charades, trying to act out the movie title Mildred Pierce, he mimicked retching, hoping to summon the words “meal dread.” Ricky was forever asking Lucy to “?’splain” herself. “Everybody thinks of Desi as flamboyant,” his longtime friend Marcella Rabwin recalled. “He wasn’t flamboyant at all. He talked loud. He said funny things. But he wasn’t a flamboyant man. He was a very serious, wonderful man who felt very deeply.”

A 1957 profile in Parade magazine was typical of the condescension Arnaz faced. The author, Lloyd Shearer, found Arnaz at the Hollywood Park racetrack, recounting how he’d just turned down a multimillion-dollar offer from the Texas oil baron Clint Murchison to buy Desilu’s studios because he feared relinquishing creative control. “How do you like that?” an unnamed woman in the next box sniffed. “Refusing $11 million in cash. Why, I remember when that Cuban was getting $250 a week for banging bongo drums.”

But the onetime bongo player was extraordinarily prescient. “I think TV is still a child,” he told the Broadway columnist Earl Wilson in the late 1950s. “Eventually, you’ll have a whole wall of your house for a screen. You can have a screen as big as your house is.”

Arnaz’s daughter, Lucie, who has herself forged a successful fifty-year career in show business, opened unpublished private family archives—letters, telegrams, medical records, manuscripts—for this book, believing that, in life and in death, much of the Hollywood ruling class never gave her father the credit he deserved. “They kind of kicked him to the curb,” she says. “Worse, they never even really gave him a place on the street to begin with.”

One who consistently credited Arnaz’s success was Lucille Ball herself, who by all accounts remained deeply in love with him even following their divorce in 1960.

“I had this feeling when I went into TV we were pioneering almost—no one really believed in it,” Ball told an interviewer in the early 1960s, in notes for a proposed memoir she later set aside. “I enjoyed the challenge and was more surprised than anyone when Lucy was a success.” Ball’s cousin Cleo Smith once told Lucie Arnaz in an oral history, “He made it all happen, and your mother certainly was the first to give him credit for all that, no matter where the relationship went. There just never would have been Desilu. There never would have been the production companies. There never would have been anything.”

Arnaz himself acknowledged his obsessiveness as a weakness. “I got a one-track mind,” he once said. “The biggest fault in my life is that I never learned moderation… I either work too hard or play too hard. If I drank, I drank too much. If I worked, I worked too much. I don’t know. One of the greatest virtues in the world is moderation. That’s the one I could never learn.” Indeed, at the pinnacle of his achievement, he became a victim of his own success, the pressures of which accelerated a spiral into alcoholism and compulsive patronage of prostitutes. And in the end, the industry that Arnaz had once dominated and done so much to build passed him by.

Depending on his mood, Arnaz would sometimes claim credit for the ideas and achievements of others, or he might be self-pitying or unduly humble. He once told the composer Arthur Hamilton, “You know me, pardner. I’m no singer. As a matter of fact, I’m not a very good actor. I can’t dance and I don’t write. I don’t do anything. But one thing I can do. I can pick people.”

That he could do. Among the television talents who cut their teeth at Desilu were Jay Sandrich, who would go on to become the principal director of The Mary Tyler Moore Show and The Cosby Show; Quinn Martin, the producer who created police procedurals like The F.B.I. and Barnaby Jones; and Rod Serling, who wrote the first episode of what became The Twilight Zone for an installment of Arnaz’s anthology series Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse. A lanky young actor named Aaron Spelling got his start in a bit part in I Love Lucy and would go on to become perhaps the most powerful television producer of the 1970s with hits like Charlie’s Angels and The Love Boat.

In the nearly seventy-five years since I Love Lucy debuted, it has been shown in more than eighty countries, dubbed into more than twenty languages, and seen by more than a billion people. In the 1980s, TV Guide judged that Lucille Ball’s face had been seen more often, by more people, than the face of any human who ever lived. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, an episode of the show was playing every hour of every day, somewhere in the world. Its characters are as familiar as our own families, and their images appear on lunch boxes, salt and pepper shakers, tea towels, pajamas, clocks, Christmas ornaments, and the postage stamps of multiple countries. On movie and television locations to this day, the doors of the “honey wagons,” the portable toilet trailers provided for the actors and crew, are not labeled “Men” and “Women” but “Desi” and “Lucy,” and no one has the slightest doubt what they mean.

The singular genius of Lucille Ball has everything to do with that, of course. But so does the singular vision of Desi Arnaz.

“Because he was an outsider and a disruptor, he asked questions that people weren’t asking and therefore changed the way we make TV,” said Amy Poehler, who directed the 2022 documentary film Lucy and Desi. “And the way we make TV is very similar to how Desi first shaped it. Both he and Lucy did not look like the faces of gatekeepers in the 1950s. His story is often, at best, minimized and, at worst, like he was lucky to be on the show. And he made the show!”

How he did so is as good a story as any he ever produced. But it takes some ’splainin’.

On Sunday evening, October 3, 1954, Ed Sullivan, the stone-faced New York newspaper columnist who had become perhaps the most awkward, unexpected television star, hosted a special celebration on his popular CBS program, Toast of the Town: a tribute to I Love Lucy, the network’s top-rated show, which was already a national institution on the eve of its fourth season on the air.

At a V-shaped banquet table bedecked with flowers, Sullivan had assembled a collection of celebrities—including Dusty Rhodes, the New York Giants outfielder who had just led his team to a World Series victory, and Howard Dietz, the lyricist of Broadway standards like “Dancing in the Dark” and “You and the Night and the Music”—to pay homage to the most beloved husband-and-wife team in contemporary entertainment, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz.

The evening’s roastmaster was a balding, avuncular, tuxedoed character named Tex O’Rourke, a onetime Texas Ranger, Wild West show performer, sports promoter, and boxing trainer who introduced Lucy and Desi as “two of my very favorite people, who have virtually dynamited their way into the hearts of all of us.” By this point, Lucille Ball needed no introduction to anyone, but O’Rourke nonetheless fancifully celebrated her as “the worst kind of redhead.” O’Rourke then turned to Arnaz, who was in fact the dominant force behind the scenes of I Love Lucy. “Down in the Caribbean, another hurricane was making up” one who “was born with a golden guitar in his lap, son of the alcalde of Santiago de Cuba, the biggest mansion in town, the biggest ranch in the hills, imported motor cars, a yacht.” Then came the revolution of 1933. “He was lucky to get out of the country, got over into Miami, a refugee, penniless… He hooked up with a fella who supplied canaries for the local drugstore.” At this, Arnaz covered his eyes in mock chagrin and demanded, “How did you find that out?” O’Rourke plowed on, “That’s my job, Desi. You might say he started at the bottom because his principal job was going around in the mornings and cleaning the birdcages. But in a way it was musical. They were singing canaries.”

O’Rourke then recounted Arnaz’s breakout as a Latin bandleader and how he and Lucy had met when Desi went to Hollywood to repeat his role as a South American football star in the film version of the Rodgers and Hart Broadway musical Too Many Girls. “From the start, it was a team through rough seas and smiling skies, but always a team,” O’Rourke said. “Sometimes a little bit hectic, but way down deep in their hearts they were always the kind of lovers that the whole world has got to love.”

When it was her turn to speak, Ball saved her warmest words for the man who, she knew better than anyone, had been most responsible for the show’s creation and for making her into one of the most famous women in the world. She and Desi had undertaken I Love Lucy at the lowest moment in their careers, when both had run out their string in the movies and were willing to leap into the still-untested, second-tier medium of television. Desi had persuaded a reluctant network and skeptical sponsor that the public would accept them—an unconventional, intermarried couple—as an all-American team. He had seen something in Lucy—and in the two of them together—that he knew would click with audiences. In personal terms, the show was also a determined attempt to save their marriage, after ten years of frequent career conflicts that kept Desi on the road with his band, by allowing them to work together at last. Now they had triumphed beyond their wildest expectations and seemed to have everything.

“His name escapes me at the moment,” Ball deadpanned, “but this guy, who seems to be in all places at once, making like an actor, a banker, a politician—in short, a producer—gets my vote as the greatest producer of all time. And I have two little Arnazes at home to prove it.” At this she cast a sexy, heavy-lidded sidelong glance at her husband, the studio audience burst into supportive laughter, and Arnaz wiped his forehead with his pocket square. “Desi, I love you,” she said. “Signed, Lucy.”

Arnaz rose last, with an earnest intensity not at all like his character Ricky Ricardo’s so-often-exasperated mien. “Thank you, sweetheart,” he began. “Thank you, Ed. You know, if it wouldn’t have been for Lucy, I would have stopped trying a long time ago, because I was always the guy that didn’t fit.” He recounted his uphill battle to get the show on the air with himself as the costar. “Finally, one executive at CBS said, ‘Well, maybe the audience would buy him, because after all they have been married…’?” Struggling to compose himself—his shoulders hunched, looking into the middle distance and not at the camera, barely holding back tears—he went on. “We came to this country, and we didn’t have a cent in our pockets. From cleaning canary cages to this night here in New York is a long ways. And I don’t think there’s any other country in the world that could give you that opportunity. I want to say thank you. Thank you, America. Thank you.”

Arnaz sat down with his head in his hands. Sullivan—a keen judge of talent who had known Desi for years and understood better than most the crucial role he had played in his wife’s success—cuffed him around the ear and drew him close in a fatherly embrace.

The gratitude that Desi Arnaz expressed that night was mutual, for against all the odds, white-bread, conformist, Eisenhower-era America had taken him and his unconventional alter ego to heart. He was adored as the man who loved Lucy, the combustible Cuban bandleader whose spluttering Spanish and long-suffering straight man’s frustration at the comic antics of his crazy wife softened into a loving embrace at the end of each episode. But Desi Arnaz was so much more than Ricky Ricardo. If Ball’s brilliant clowning—her beauty, her mimicry, her flexible face and fearless skill at physical comedy—was the artistic spark that animated I Love Lucy, Arnaz’s pioneering show-business acumen was the essential driving force behind it. He was, as NPR’s Planet Money once put it, the man who “invented television.”

“There’s a misconception that we—that Desi wasn’t all that important to the show,” Madelyn Pugh Davis, the founding cowriter of I Love Lucy, would recall years after his death. “And Desi was what made the show go. And he also knew that she was the tremendous talent. He knew that. But he was the driving force, and he was the one who held it together. People don’t seem to realize that.”

Today, nearly four decades after his death, Arnaz the performer remains a widely recognizable figure—“one of the great personalities of all time,” as his friend the dancer Ann Miller once put it. Much less well understood is the seminal role he played in the nascent years of television, helping to transform its production methods, and transforming himself, a successful but second-tier Latin bandleader, and his wife, a journeyman actress in mostly forgettable B movies, into cultural icons.

It was Arnaz (and I Love Lucy’s head writer and producer, Jess Oppenheimer) who assembled the world-class team of Hollywood technicians who figured out how to light and film the show in front of a live studio audience, with three cameras in sync at once—a then-pathbreaking method that soon became an industry standard for situation comedies that endures to this day. It was his ability to preserve those episodes on crystalline black-and-white 35-millimeter film stock that led to the invention of the rerun and later to the syndication of long-running series to secondary markets. This innovation also made it possible for the center of network television production to move from New York to Los Angeles and created the business model that lasted unchallenged for the better part of seven decades, until the streaming era established a competing paradigm.

“I Love Lucy was a crucial part of entertainment in this country,” said Norman Lear, the creator of the landmark situation comedy All in the Family and many other shows. “Lucy and Desi—I think it can be said they pretty much opened the door of Hollywood to America, and to the situation comedy. There was only one Lucy and one Desi, and between them, they knew what it took. He was a great businessman in the persona of a wonderful entertainer.”

It was Arnaz’s unselfconscious portrayal of the paterfamilias of an ethnically mixed family that proved a vivid contrast to the all-WASP lineup of contemporary sitcoms like Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver, and made him a breakthrough cultural figure in a country that would soon be transformed by growing social justice activism and a greater acceptance of diversity as a strength.

“In real life or fiction, neither Desi nor Ricky ever betrayed his Latino identity,” the columnist Miguel Perez would write in the New York Daily News after Arnaz’s death. “When Americans saw him on the screen in the 1950s, and when the world sees him now and in the future, they will not see Arnaz playing one of those criminal or drug-dealer roles usually given to Latinos. They see him as the head of an American family who, in spite of his accent and Cuban quirks, is realizing the Latino-American dream.”

Finally, it was Arnaz whose name came first in Desilu, the production company that he and Ball founded, which became the largest producer of television content in the world in the late 1950s; provided the studio space where many other shows, including those of Danny Thomas and Dick Van Dyke, were staged; and eventually spawned the global entertainment juggernauts Mission: Impossible and Star Trek.

From the start, Desi Arnaz’s story is that of an unrelenting go-getter who repeatedly defied conventional expectations and saw creative ways forward when others did not. He was born a son of the Cuban aristocracy, but his family lost everything and was forced to flee in the 1933 Cuban revolution that followed the overthrow of the repressive American-backed regime of Gerardo Machado. Arnaz, seventeen years old, wound up penniless in Florida. A future that had once envisioned college at Notre Dame and then a law degree disappeared in favor of a high school diploma and reinvention as a self-taught musician in Miami Beach. Eventually, he formed his own band and helped fuel the demand for Latin music that was sweeping the country, promoting the conga dance craze, first in Miami and then as a nightclub headliner in New York.

Arnaz often attributed his willingness to take risks to this youthful dispossession and trauma. The painful corollary was that even at the peak of his fame and success, he would never quite fit comfortably in either the mainstream white culture or the Mexican American community that predominated in his adopted hometown of Los Angeles. He was a refugee, not an immigrant, and he never forgot it. “If you feel betrayed by your own country, you’re always on the run,” observed the Cuban American playwright Eduardo Machado, himself a childhood refugee, from Fidel Castro’s Cuba. “And no matter how talented you are, and no matter how many things you get, you’re always being told, ‘This isn’t real. Our real life is in Cuba.’?” He added, “You feel like a phony, because you don’t know who you are. I think the more you make it, the more you feel like a phony.” Even in complimenting Arnaz’s business prowess, Hollywood resorted to crude stereotypes. “Yes, he’s the wetback they all waited for, the wetback TV was created for,” the Oscar-winning lyricist Sammy Cahn wrote for a parody roast of Arnaz to the tune of “That Old Black Magic.”

Arnaz endured endless slights from an entertainment establishment that looked askance at his accent, his ethnicity, and his perpetual public image as a second banana to his superstar wife. Too many valet parking attendants and hotel clerks addressed him as “Mr. Ball.” Well into the 1970s, newspapers and magazines routinely reproduced his spoken words in interviews in comically accented dialect, as if he actually were Ricky Ricardo. Network executives at first underestimated him, but they did so at their peril, because his explosive negotiating style often won out in the end. At the peak of Arnaz’s power, in the late 1950s, his longtime secretary Johnny Aitchison recalled that an important business caller once complained, “?‘My God, I can get to the president easier than I can get to Desi Arnaz,’ and I said, ‘Yeah, but he’s not doing a show every week, too.’?”

Arnaz himself made fun of his mangled pronunciation—“He spoke no known language,” his friend George Schlatter said—and his accent was almost as thick in real life as it was on the air. He proudly kept a sign in his house proclaiming ENGLISH BROKEN HERE. He was prone to malapropisms like “goosepimple pie,” and once in a game of charades, trying to act out the movie title Mildred Pierce, he mimicked retching, hoping to summon the words “meal dread.” Ricky was forever asking Lucy to “?’splain” herself. “Everybody thinks of Desi as flamboyant,” his longtime friend Marcella Rabwin recalled. “He wasn’t flamboyant at all. He talked loud. He said funny things. But he wasn’t a flamboyant man. He was a very serious, wonderful man who felt very deeply.”

A 1957 profile in Parade magazine was typical of the condescension Arnaz faced. The author, Lloyd Shearer, found Arnaz at the Hollywood Park racetrack, recounting how he’d just turned down a multimillion-dollar offer from the Texas oil baron Clint Murchison to buy Desilu’s studios because he feared relinquishing creative control. “How do you like that?” an unnamed woman in the next box sniffed. “Refusing $11 million in cash. Why, I remember when that Cuban was getting $250 a week for banging bongo drums.”

But the onetime bongo player was extraordinarily prescient. “I think TV is still a child,” he told the Broadway columnist Earl Wilson in the late 1950s. “Eventually, you’ll have a whole wall of your house for a screen. You can have a screen as big as your house is.”

Arnaz’s daughter, Lucie, who has herself forged a successful fifty-year career in show business, opened unpublished private family archives—letters, telegrams, medical records, manuscripts—for this book, believing that, in life and in death, much of the Hollywood ruling class never gave her father the credit he deserved. “They kind of kicked him to the curb,” she says. “Worse, they never even really gave him a place on the street to begin with.”

One who consistently credited Arnaz’s success was Lucille Ball herself, who by all accounts remained deeply in love with him even following their divorce in 1960.

“I had this feeling when I went into TV we were pioneering almost—no one really believed in it,” Ball told an interviewer in the early 1960s, in notes for a proposed memoir she later set aside. “I enjoyed the challenge and was more surprised than anyone when Lucy was a success.” Ball’s cousin Cleo Smith once told Lucie Arnaz in an oral history, “He made it all happen, and your mother certainly was the first to give him credit for all that, no matter where the relationship went. There just never would have been Desilu. There never would have been the production companies. There never would have been anything.”

Arnaz himself acknowledged his obsessiveness as a weakness. “I got a one-track mind,” he once said. “The biggest fault in my life is that I never learned moderation… I either work too hard or play too hard. If I drank, I drank too much. If I worked, I worked too much. I don’t know. One of the greatest virtues in the world is moderation. That’s the one I could never learn.” Indeed, at the pinnacle of his achievement, he became a victim of his own success, the pressures of which accelerated a spiral into alcoholism and compulsive patronage of prostitutes. And in the end, the industry that Arnaz had once dominated and done so much to build passed him by.

Depending on his mood, Arnaz would sometimes claim credit for the ideas and achievements of others, or he might be self-pitying or unduly humble. He once told the composer Arthur Hamilton, “You know me, pardner. I’m no singer. As a matter of fact, I’m not a very good actor. I can’t dance and I don’t write. I don’t do anything. But one thing I can do. I can pick people.”

That he could do. Among the television talents who cut their teeth at Desilu were Jay Sandrich, who would go on to become the principal director of The Mary Tyler Moore Show and The Cosby Show; Quinn Martin, the producer who created police procedurals like The F.B.I. and Barnaby Jones; and Rod Serling, who wrote the first episode of what became The Twilight Zone for an installment of Arnaz’s anthology series Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse. A lanky young actor named Aaron Spelling got his start in a bit part in I Love Lucy and would go on to become perhaps the most powerful television producer of the 1970s with hits like Charlie’s Angels and The Love Boat.

In the nearly seventy-five years since I Love Lucy debuted, it has been shown in more than eighty countries, dubbed into more than twenty languages, and seen by more than a billion people. In the 1980s, TV Guide judged that Lucille Ball’s face had been seen more often, by more people, than the face of any human who ever lived. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, an episode of the show was playing every hour of every day, somewhere in the world. Its characters are as familiar as our own families, and their images appear on lunch boxes, salt and pepper shakers, tea towels, pajamas, clocks, Christmas ornaments, and the postage stamps of multiple countries. On movie and television locations to this day, the doors of the “honey wagons,” the portable toilet trailers provided for the actors and crew, are not labeled “Men” and “Women” but “Desi” and “Lucy,” and no one has the slightest doubt what they mean.

The singular genius of Lucille Ball has everything to do with that, of course. But so does the singular vision of Desi Arnaz.

“Because he was an outsider and a disruptor, he asked questions that people weren’t asking and therefore changed the way we make TV,” said Amy Poehler, who directed the 2022 documentary film Lucy and Desi. “And the way we make TV is very similar to how Desi first shaped it. Both he and Lucy did not look like the faces of gatekeepers in the 1950s. His story is often, at best, minimized and, at worst, like he was lucky to be on the show. And he made the show!”

How he did so is as good a story as any he ever produced. But it takes some ’splainin’.

Recenzii

"Deeply researched and clear-eyed about Arnaz’s talents as well as his struggles. . . . Purdum gives us Arnaz’s life story, and it’s an often surprising one."

"In many ways, Desi Arnaz was Ricky Ricardo, the character he played on television—creative, hardworking, excitable, lovable, an embracing personality, a natural entertainer. . . . Mr. Purdum tells this classic rise-and-fall story with an élan his subject would appreciate."

"Todd S. Purdum’s deeply researched, insightful and enjoyable biography gives Arnaz his due as an entertainer and a savvy businessman."

"Desi Arnaz’s life ricocheted between privilege and economic hardship, creative peaks and alcoholic lows — the stuff of high drama. But it was comedy that secured his legacy. . . . As Todd S. Purdum relates in his intimate, often poignant biography, Arnaz was the driving force behind [I Love Lucy] and a pioneer of early television. . . . A nuanced portrait of both Arnaz’s gifts and his tragic shortcomings."

"Revelatory . . . gives its subject long-overdue acknowledgement and appreciation."

"[Arnaz's] legacy is forever and undeniable. Purdum does a bang-up job of spotlighting Arnaz's many vital contributions to television history in this lively and engaging biography."

"Purdum successfully celebrates the vision and talent of Cuban-born actor Desi Arnaz. . . . [This] honest reflection of a complicated man is poignant and heartfelt."

"A scintillating biography of I Love Lucy costar Desi Arnaz. . . . A vividly rendered tale of a TV tycoon’s spectacular rise and ignominious fall."

"In many ways, Desi Arnaz was Ricky Ricardo, the character he played on television—creative, hardworking, excitable, lovable, an embracing personality, a natural entertainer. . . . Mr. Purdum tells this classic rise-and-fall story with an élan his subject would appreciate."

"Todd S. Purdum’s deeply researched, insightful and enjoyable biography gives Arnaz his due as an entertainer and a savvy businessman."

"Desi Arnaz’s life ricocheted between privilege and economic hardship, creative peaks and alcoholic lows — the stuff of high drama. But it was comedy that secured his legacy. . . . As Todd S. Purdum relates in his intimate, often poignant biography, Arnaz was the driving force behind [I Love Lucy] and a pioneer of early television. . . . A nuanced portrait of both Arnaz’s gifts and his tragic shortcomings."

"Revelatory . . . gives its subject long-overdue acknowledgement and appreciation."

"[Arnaz's] legacy is forever and undeniable. Purdum does a bang-up job of spotlighting Arnaz's many vital contributions to television history in this lively and engaging biography."

"Purdum successfully celebrates the vision and talent of Cuban-born actor Desi Arnaz. . . . [This] honest reflection of a complicated man is poignant and heartfelt."

"A scintillating biography of I Love Lucy costar Desi Arnaz. . . . A vividly rendered tale of a TV tycoon’s spectacular rise and ignominious fall."

Descriere

An illuminating biography of Desi Arnaz, who forever transformed television through his trailblazing success both in front of the camera in I Love Lucy and behind it as the genius driving Desilu Productions, exploring a bold and turbulent life marked by addiction and divorce.