Desi Arnaz

Autor Todd S Purdumen Limba Engleză Hardback – 28 ian 2026

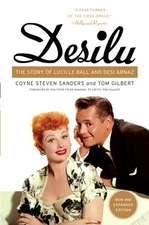

Desi Arnaz is a name that resonates with fans of classic television, but few understand the depth of his contributions to the entertainment industry. In Desi Arnaz, Todd S. Purdum offers a captivating biography that dives into the groundbreaking Latino artist and businessman known to millions as Ricky Ricardo from I Love Lucy. Beyond his iconic role, Arnaz was a pioneering entrepreneur who fundamentally transformed the television landscape.

His journey from Cuban aristocracy to world-class entertainer is remarkable. After losing everything during the 1933 Cuban revolution, Arnaz reinvented himself in pre-World War II Miami, tapping into the rising demand for Latin music. By twenty, he had formed his own band and sparked the conga dance craze in America. Behind the scenes, he revolutionized television production by filming I Love Lucy before a live studio audience with synchronized cameras, a model that remains a sitcom gold standard today.

Despite being underestimated due to his accent and origins, Arnaz’s legacy is monumental. Purdum’s biography, enriched with unpublished materials and interviews, reveals the man behind the legend and highlights his enduring contributions to pop culture and television. This book is a must-read biography about innovation, resilience and the relentless drive of a man who changed TV forever.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 62.02 lei Precomandă | |

| Simon&Schuster – 2 iul 2026 | 62.02 lei Precomandă | |

| Hardback (2) | 107.53 lei 26-38 zile | |

| Simon&Schuster – 3 iul 2025 | 107.53 lei 26-38 zile | |

| Thorndike Press, a Cengage Group – 28 ian 2026 | 279.88 lei 22-36 zile |

Preț: 279.88 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 420

Preț estimativ în valută:

49.50€ • 57.33$ • 42.98£

49.50€ • 57.33$ • 42.98£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 30 martie-13 aprilie

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781420531671

ISBN-10: 1420531670

Dimensiuni: 144 x 223 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.79 kg

Ediția:Text mare

Editura: Thorndike Press, a Cengage Group

ISBN-10: 1420531670

Dimensiuni: 144 x 223 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.79 kg

Ediția:Text mare

Editura: Thorndike Press, a Cengage Group

Notă biografică

Todd S. Purdum is a veteran journalist and author. In a career of more than forty years, he has written widely about politics and culture, starting at The New York Times, where he spent twenty-three years, covering politics from city hall to the White House, later serving as diplomatic correspondent and Los Angeles bureau chief. He has also been a staff writer at Vanity Fair, Politico, and The Atlantic. He is the author of Something Wonderful: Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Broadway Revolution and An Idea Whose Time Has Come: Two Presidents, Two Parties, and the Battle for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife, the former White House press secretary Dee Dee Myers, with whom he has two grown children.

Extras

Chapter One: Once on an Islandone ![]() ONCE ON AN ISLAND

ONCE ON AN ISLAND

He was a Pisces, born on an island, and for the rest of his life, in happy times and times of bad trouble, he would always return to the sea. He was an only child—a rarity in the Catholic culture of his time and place—a handsome, dark-eyed boy. In surviving formal photographs, he is sober, in his sailor suits and white linens, or in a pirate costume and painted mustache at an early birthday party. He looks mature beyond his years, and that is perhaps not surprising: From the beginning, Desiderio Alberto Arnaz y de Acha was raised as a prince.

He was born on March 2, 1917, in a spacious Spanish colonial house on Santa Lucia Street in Santiago de Cuba, the island’s original capital and still its second-largest city after Havana. Not twenty years earlier, Theodore Roosevelt had stormed up the San Juan Heights, on Santiago’s northeastern fringes, in the Spanish-American War. He had pronounced it a “quaint, dirty old Spanish city,” though he allowed that “it was interesting to go in once or twice, and wander through the narrow streets with their curious little shops and low houses of stained stucco, with elaborately wrought iron trellises to the windows and curiously carved balconies.” Other visitors might have likened the city’s hilly, bayside topography to San Francisco’s, and its polyglot, bon temps rouler, music-filled atmosphere to that of New Orleans. To this day, the region is known as la tierra caliente, as much for the natives’ fiery temperaments as for the high temperatures.

Situated at the head of a wide, safe harbor on the southeastern, leeward side of the island, Santiago had been settled by the Spanish in 1515; over the next three hundred years the city was successively plundered by French and English forces and a rogues’ gallery of pirates. The aftermath of the slave uprising in neighboring Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, in the 1790s brought an influx of newly freed Africans—together with fleeing slave owners and their human chattel—that created an unusually rich demographic mix, importing African musical, culinary, and cultural influences and establishing sugarcane—“white gold”—as the island’s dominant cash crop. Tobacco farming, copper mining, and fishing were Santiago’s other industries, and in 1862 the Bacardí rum distillery was founded there, spreading its signature sugar-based spirit across the Caribbean and the Americas.

“Something about Oriente invites exaggeration,” the journalist Patrick Symmes wrote of the region around Santiago. “It is the hottest part of Cuba, the most mountainous, the first settled, and the earliest to achieve glory and shame…. There were men present at the founding of the city who had known Columbus himself, and the 1515 date was so early that it rooted Santiago more in the European Middle Ages than in the new world to come. Santiago was the first capital of Cuba, reigning for forty years before eventually losing out to Havana, an insult never forgotten. The city served as a kind of Jerusalem to the Americas, spreading the new faith of conquest, and the new tongue of Castilian.”

And, Symmes continued, “white or black, poor or rich, the Santiaguero insisted with a straight face that fruit is riper, the sun is stronger, the women more passionate, the politics more sincere, the talk more profound, the cemeteries more grand, even the night darker, than elsewhere in Cuba.” Residents of Oriente “insisted that not only was Cuban music the best music in the world, which everyone already knew, but Oriente was the only source of Cuban music.”

By the time of Desi’s birth, la familia Arnaz (properly pronounced Ar-NAAS, not Ar-NEZZ, as Hollywood would later Anglicize it) was firmly established as Santiago aristocracy. The matriarch, Dolores Vera y Portes, had fled Seville with her parents in the early nineteenth century when Joseph-Napoléon Bonaparte, the emperor’s older brother, invaded Spain and exiled the family. The Vera family bought or was granted land in and around Santiago and built a hilltop villa on Cayo Smith, a tiny islet near the mouth of Santiago Bay. Dolores, an only child, would eventually marry Manuel Arnaz y Cobreces, the municipal fire chief of Santiago, who in 1869 would be appointed the city’s mayor by Queen Isabella II of Spain. (The surname Arnaz itself is of Basque origin, after the town of Arnaz in Spain; in France it is rendered Arnault and in Italy Arnaldi.) Manuel and Dolores’s only son, Desiderio Arnaz y Vera, the first Desi in the family line, was born in 1857. His family sent him back to Spain to study medicine at the University of Seville, and he returned to Santiago as a practicing physician. In 1884, he married Rosa Alberni y Portuondo, a member of the Cuban nobility descended from an old and illustrious Santiago family. (Her great-grandfather, the first count of Santa Inés, had also been mayor.) She would bear Dr. Arnaz seven children: three sons and four daughters. One of those sons, born in 1894, was also christened Desiderio, and he would become the father of the family’s third Desi, who won worldwide fame.

The first Desiderio Arnaz’s growth to maturity had coincided with the rise of the movement for Cuban independence from Spain, a drive that began in 1868 when a small plantation owner, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, freed his slaves and proclaimed Cuba a sovereign state. This sparked a ten-year war that left two hundred thousand people dead but resolved nothing—though the resulting economic disaster led for the first time to heavy American investment in Cuban real estate and agriculture. In 1886, a royal Spanish decree finally abolished slavery on the island. And in 1895, the Second War of Independence began, this time led by José Martí, a poet, journalist, and lawyer who had been an active lobbyist for the Cuban cause from his exile in the United States. Martí was killed in his first battle and is revered to this day as a national hero (both by Cubans on the island and Cubans in exile; one of the few points on which they agree). His tomb in Santiago’s Santa Ifigenia Cemetery is a shrine. In 1898, spurred on by a group of neocolonialist American politicians (including Theodore Roosevelt, who was then assistant secretary of the navy, and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts) and whipped into a frenzy by sensationalist press coverage of wartime Spanish atrocities and the mysterious sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor, the United States joined the Cuban rebels to repulse Spanish rule—and, not coincidentally, secure the U.S. economic stake in the island. (Many historians contend that the Cubans were already winning and did not need American intervention.) In any case, the effort was short and successful—a “splendid little war,” Secretary of State John Hay called it—and climaxed in the assault on the San Juan Heights outside Santiago on July 1, 1898. That cavalry charge in turn swiftly propelled Roosevelt to the governorship of New York later that year, to the vice presidency two years later, and ultimately to the presidency upon the assassination of William McKinley, in 1901.

But Cuba’s nominal independence came at a high price. The island traded its status as a Spanish colony for effective subjugation to the United States, beholden to American strategic and commercial interests. Congress passed the Platt Amendment, which was also enshrined in the new Cuban constitution, allowing the United States to intervene with military force in Cuban internal affairs as it saw fit. The next thirty years would see steadily increasing American influence and entanglement with a succession of Cuban governments, whose leadership was largely made up of veterans of the 1895–1898 war.

Arnaz family lore holds that Desiderio was attached to Roosevelt’s cavalry forces at San Juan Hill, though hard evidence is lacking. What is not in dispute is that Don Desiderio achieved the rank of captain in the Liberation Army, “obtained after bloody battles in the fields of Cuba,” as one of his obituaries would later put it, and the Arnaz dynasty became firmly entwined in the Cuban-American alliance. As a youth, the doctor’s son Desiderio II was apparently a handful, academically capable but easily distracted and too curious and querulous for the Catholic brothers who taught him. So his parents sent him off to school in America, to the small town of Sidney, New York, near Binghamton, a destination chosen for reasons that his descendants never understood. He spoke not a word of English, lived with an American family, and had a tough time of it. His family wanted him to follow his father’s career and become a physician. Instead, he eventually enrolled at the Southern College of Pharmacy in Atlanta (now part of Emory University), and in 1913 he earned the pharmacist degree that would let him style himself for the rest of his life, like his father before him, as “Dr. Arnaz.” The young Desiderio returned to Santiago, opened his own drugstore, and in 1916 married Dolores de Acha y de Socias, who had been born in the neighboring Dominican Republic in 1896 and was once declared one of the twelve most beautiful women in Latin America. Dolores, known to everyone as Lolita, gave birth to their only son the next year, and the youngest Desi would grow up in an atmosphere of unquestioned privilege. Lolita’s father, Alberto de Acha, had started as a Bacardí rum salesman, loading mules with as many bottles as they could hold and hawking his load in Santiago and the surrounding countryside. He later wound up as a vice president of the company, and when Bacardí was reorganized as a stock corporation in 1919, he received shares valued at ten thousand dollars (nearly two hundred thousand dollars in 2020s currency), a windfall that would benefit his family for decades to come.

Besides running his pharmacy, the younger Dr. Arnaz operated three farms in the countryside surrounding Santiago, one of them raising beef, another a dairy farm, and a third producing poultry and pork, with an accompanying slaughterhouse. (A Desilu corporate press release would later claim the family’s holdings amounted to one hundred thousand acres, but that may have been Hollywood hype.) These extensive enterprises evidently did not scratch every itch, and in 1923 Desiderio II followed in his grandfather Manuel’s footsteps, becoming mayor of Santiago, at age twenty-nine the youngest in the city’s history. In his case, however, the office came not by royal appointment but after a vigorous election campaign in which he ran on a reform platform of improving the city’s public works and infrastructure, a program that would eventually lead to his reputation as el alcalde modelo, the model mayor. Arnaz put management of his pharmacies in the hands of employees and set about remaking his hometown, which lacked a reliable water supply, adequate sanitation, and paved streets.

He built parks and a municipal swimming spa, installed the city’s first traffic light, inaugurated the first radio telegraph service, celebrated the creation of an airfield by Pan American Airways, and greeted a visiting Charles Lindbergh in 1929. But his crowning achievement was the restoration of the crumbling alameda on the city’s waterfront, where he built graceful welcoming arches, a seawater swimming pool, a wide park, and a striking clock tower, which the local chamber of commerce dedicated in his honor. The alameda opened in 1928 with a parade and the crowning of a queen, escorted by the eleven-year-old Desi III, “the simpatiquísimo son of our Municipal Mayor, who will be the representative of his popular father in this simpatico event,” as one local newspaper put it.

“I don’t rest,” a contemporary newspaper quoted el alcalde modelo as saying. “I am always running at a trot.” But, he added, he was ecstatic at the public’s support. “I am convinced that all we need here is initiative…. It is possible you think me crazy, but I think to pull Santiago out of the miserable situation that exists—ruined and forgotten—we have to do some crazy acts, and I will do them.”

As the only son of Santiago’s most influential citizen, Desi III reaped the benefits and bore the high expectations that came with such stature. In a family scrapbook kept by Mayor Arnaz, there are pictures of little Desi, always meticulously dressed and groomed. In one, he is decked out as a swarthy buccaneer, surrounded by a gang of similarly outfitted boys and girls at his birthday party, when he appears to be about six or seven. “Desi, always social, with more friends than anyone else,” his father noted in the caption. In another photograph from the same time, Desi holds a checkered starter’s flag and, looking slightly frightened, stands surrounded by a raft of boys in small racing cars, ready to judge a soapbox derby in Cespedes Park, the city’s central square, facing the Santiago Cathedral and city hall. Mayor Arnaz’s caption combines parental pride and fatherly ego: “He was always a leader, as I taught him to be.”

Indeed, young Desi was taught to take his place among the island’s elite, and discipline was expected. In summers, in the country, he rose at dawn with other farmhands to milk cows and perform chores. For as long as he could remember, he rode a horse well and herded cattle; for his tenth birthday, he received a fine Tennessee walking horse. He was responsible for earning his own spending money. But from the beginning, there was also a touch of the devil in the boy, and he was more than a little spoiled. When he was four, with his family now living in a larger gray stucco colonial house in San Basilio Street, directly across from his Arnaz grandparents and about four blocks from city hall, Desi tried using the drawers of his father’s bedroom chiffonier as steps “to reach a lovely pearl-handled revolver I knew he kept in the first drawer from the top, safely out of my reach, or so he thought. I was grabbing the revolver when the chiffonier tumbled forward, pinning me under and cutting a deep gash in my chin and head while simultaneously causing the revolver to fire and scaring the hell out of me.” The bullet struck an antique cuckoo clock, which proceeded to chirp frantically as his nanny rushed in and extricated him and took him across the street, where his grandfather the doctor stitched him up with a needle and thread.

On San Basilio Street, his house was forbidding from the outside, with heavy wooden shutters and wrought-iron bars at the windowed facade. But the thick old walls made the home cool and shaded inside, and there was a gracious interior garden courtyard open to the sky and a front porch with rocking chairs facing the street. Mosaic tile covered the floor of the living room, which featured a plush sofa and chairs and an oil painting of Desi and his parents. Old-fashioned brass lamps shed gentle light, and a “monstrous French player piano” that no one in the family could play added an elegant touch, Arnaz’s childhood friend Marco Rizo would recall. Desi would have grown up listening to the sounds of streetcars running down the middle of the cobblestoned avenues and the cries of street vendors hawking everything from peanuts to produce to household goods. He would have smelled the scent of horses, which were still a common means of daily transportation and commerce in his childhood. And, always and everywhere, he would have heard music, which streamed across the city day and night. “Music was something we both ate, drank, and bathed in from birth,” Rizo recalled. Desi’s uncle Eduardo de Acha played the guitar, sang, and composed songs, and another uncle, Rafael de Acha, was also musical. Somewhere along the way, Desi himself learned to play the guitar, but he never learned to read music, though he did take a few lessons from Don Alberto Limonta, an Afro-Cuban who taught many of the city’s privileged sons. “No, he wasn’t a prodigy who could play a Brahms concerto on an instrument by the age of four,” Rizo recalled, “but he definitely stood out as an appreciator of anything musical from childhood on.”

Desi’s favorite place by far was his family’s summer home on Cayo Smith. The cayo, or key, was a small island at the mouth of Santiago Bay, perched just below El Morro, the rockbound Spanish fort that guarded the entrance to the harbor. Named for the wealthy British slave trader who had once owned it, el Cayo rose from the blue Caribbean like “a little mountain coming out of the water,” Desi would remember decades later. The island was ringed with fishing boats, crested with a white hilltop church, and dotted with wooden “bungalows”—actually, spacious vacation retreats for the city’s elite. There were no cars or streets, and an energetic teenager could circle the little island’s perimeter in no more than forty-five minutes on foot. Desi and his friends often swam around it instead. It was also the scene of an adolescent misadventure more embarrassing than Desi’s climb up his father’s dresser.

Casa Arnaz, perched on a hill and with polished hardwood floors and shuttered windows, opened onto a seventy-five-foot pier with a two-slip boathouse, berthing the sleek speedboat that took Desi’s father to work at city hall each morning and Desi’s own eighteen-foot, wooden Norwegian fishing skiff. It was in one of the dressing rooms of that boathouse, still ignorant of the facts of life at age twelve, that the boy undertook to learn. His co-conspirator was the same age, the daughter of his family’s Black cook. “After locking the door, we began to experiment about how this thing was done,” he would recall. “Neither of us had the slightest idea… but I was obviously anxious and noticeably ready for action and getting more and more frustrated by the minute. We had tried a number of ridiculous experiments and were working on a new one when there was a loud knock on the door. It was her mother the cook, asking her to come out. I didn’t have any trouble putting on my trunks in a hurry. The small proof of my anxiety had disappeared. I wish I could have done the same.”

Frantic to escape, Desi dove out a high window straight into the water below and swam as long as he could under the surface to a neighboring pier, where he heard his uncle Salvador, his father’s younger brother, calling out: His mother had seen the whole tableau in pantomime. That night, Desi’s father took him into his study and let him have it. “Have you ever seen me insult your mother?” Mayor Arnaz demanded. “Have you ever seen me embarrass her or make her ashamed of me?… You listen to me, young fellow, and listen good. Don’t you ever insult your mother that way again or embarrass her as you did. Now get the hell out of here.”

In an unpublished draft of his memoir decades later, Desi would reflect, “I thought in later years it was really very nice of my dad to treat the incident that way, because the wrong kind of approach at that time would have probably made me awful scared of sex and ashamed of having to find out about it. But he put it on the basis of being a gentleman and respecting your mother. If you’re going to do that thing, do it privately and not in front of your house.” Alas, this was a lesson that Desi, man and boy alike, seemed destined to never quite learn.

Desi’s sexual education culminated three years later, at fifteen, when his uncle Salvador, who owned a small soap factory, took him to Casa Marina (“the finest whorehouse in Santiago,” Desi would recall), which featured live music, elegant parlors, and an elite clientele. Desi assumed that the outing had come at the direction of his father, and there in the deluxe bordello “I learned the whole deal,” as he would later put it, from “ladies of the house” who were “all young and clean and treated me very kindly, very nicely, very tenderly, and very expertly. Sometimes I wonder if perhaps it is not better to educate a young boy like that instead of letting him get into a lot of trouble trying to find out for himself.”

In fact, this formative experience would cause Desi plenty of trouble in future years, because he had internalized the mixed messages about sex and gender reflected in the patriarchal, chauvinist Latin culture in which he was raised. On the one hand, sex with whores was there for the asking while nice women, respectable women—like his mother, elegant and aloof—were to be treated with courtesy extending to gallantry. On the other hand, the society of his class and time subjugated even such respected women to second-class, subordinate roles and a cruel double standard: Men could stray sexually, unpunished; women could not. Desi’s grandfather Arnaz kept a casa chica, a second home with his mistress and multiple illegitimate children, on a small farm in El Caney north of Santiago. Marco Rizo recalled that Mayor Arnaz also “kept himself satisfied with two longstanding private relationships with women outside his marriage,” a reality known to Santiago society but apparently not to Lolita. When Desi’s grandfather, a non-churchgoer, was dying, his wife implored her grandson to bring a priest to pray with Dr. Arnaz. “Ponga el corazon con Dios” (“Put your faith in God”), the priest counseled. “Ponga el corazon con Dios y el rabo tiezo” (“Put your faith in God and a stiff prick”), Grandfather Arnaz replied.

Desi would struggle throughout his life to make sense of these dichotomies. “I got very mad at my father sometimes,” he would recall decades later. “I was the only son, and due to his job, or whatever the hell it is, he wouldn’t be home until late, and everything else, and my mother used to adore this guy and her whole life was him and I used to say to her, ‘What the hell? What is this with you?’ you know. ‘You’re like a slave to this guy. You treat him like he’s a goddamn king or something.’ My mother said something that I’ll never forget. She said, ‘Yeah, that’s true, I treat him like a king.’ I said, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘That’s the only way I can be a queen.’?”

Indeed, by all accounts, Dolores de Acha went through life with a regal air and was a difficult, domineering woman. “Lolita came from a very privileged level of society in Cuba,” Lucille Ball’s cousin Cleo Smith, who came to know her in later years, would recall. “I mean, you have help by the dozens, and never lifted a finger, and never learned to cook, and you never did a bit of housework, you never did anything.” The longtime Ball-Arnaz family friend Marcella Rabwin was more succinct: “Lolita was impossible for anyone to love.”

Of Mayor Arnaz himself, another family member would recall, “He didn’t like people that weren’t sincere. He wanted everything to be just right, no deviation from the way things should be.” Rabwin would remember, “There was a certain egotism in Dr. Arnaz,” and after Desi III became world famous, his father “did not want Desi, in his great importance, to be more important than he had been. There was a sort of rivalry thing there. Desi didn’t really feel it, but I think the father did, because he wouldn’t let Desi have the last word. If they were talking and there was any slight difference of opinion, Dr. Arnaz prevailed.” Decades later, Desi’s daughter, Lucie, who witnessed her father’s interactions with her grandparents as a young adult, would judge that Desi had lacked the deepest sort of parental nurturing and emotional support. “The mother-father strange relationship that never really was embracing, never really was loving, never was unconditional,” she said. “It was always, ‘You have to prove yourself…. You’re not enough if I don’t have enough,’ and that’ll kill you, you know.”

In his own memoir, Desi would recall his father’s blend of sternness and indulgence. Desi’s high school was the rigorous Colegio de Dolores, led by the Jesuit order, where a decade later a boy from the provinces named Fidel Castro would also be a student. “Neither an overt rebel nor a dreamer,” Marco Rizo would recall, Desi “was always a person of action.” When he was a teenager, his parents gave him a car, and he drove around “with as many girls as he could fit in it,” Rizo said.

In his junior year of high school, Desi realized to his chagrin that he was about to fail geometry and trigonometry and would not be able to pass his final exams—a potential crisis for a student who aspired to attend college in the United States (he and his parents often spoke of sending him to Notre Dame, a storied Catholic school and football powerhouse) and then law school. “So, what do you want from me?” Mayor Arnaz demanded when Desi gave him the news. “I’m sorry, Dad, I don’t know what happened,” the son explained, and the father retorted, “I know what happened. You discovered girls, and from the report I got from my soap-making brother, you didn’t have any trouble learning that subject.” Still, the mayor agreed to help out, dispatching a police sergeant on the Palacio Municipal detail, who was a whiz at math, to tutor Desi privately.

In March 1933, when Desi turned sixteen, his father wrote him a letter of advice that he would keep for the rest of his life. “You are now sixteen, and in my book, that means you are no longer a child; you are a man,” Mayor Arnaz wrote. He warned his son that life was like the road from Santiago to the family’s farm in nearby El Cobre, sometimes smooth and beautiful, sometimes ugly and rough. “Remember, good things do not come easy, and you will have your share of woe—the road is lined with pitfalls. But you will make it, if when you fail, you try and try again. Persevere. Keep swinging.” It was timely advice. Desi’s father might have had some inkling of just how much that counsel would be needed in the months and years ahead, because by 1933 the Cuban political and social establishment that the senior Arnaz had thrived in was falling to pieces—into violence, repression, and turmoil.

Mayor Arnaz’s political career had coincided with the rise of Cuba’s most powerful figure, President Gerardo Machado. One of the youngest generals in the Cuban War of Independence, Machado had aligned himself in the 1910s with liberal forces opposing the American-backed regime. He won office in 1924 as the Liberal Party candidate, campaigning on a platform of “water, roads, and schools.” He pledged to serve only one term and to seek abrogation of the Platt Amendment allowing American intervention in Cuban political affairs. He undertook an ambitious plan of public works, winning the support of local officials beholden to him. His efforts were responsible for the National Highway that stretches across the entire island and the Hotel Nacional in Havana. The hotel quickly became a deluxe destination for the American tourists who had been flooding to Cuba since the advent of Prohibition in 1920, a phenomenon celebrated by Irving Berlin in his song “I’ll See You in C-U-B-A,” which promised a rum-soaked paradise where “dark-eyed Stellas light their fellers’ panatelas.”

Sugar production thrived, American investors prospered, and Cuba became known as “the Switzerland of the Americas.” But soon enough, Machado waffled on his pledge to overturn the Platt Amendment and reneged on his promise to serve just one term, running again, this time unopposed, in 1928 (with the acquiescence of President Calvin Coolidge) and forcing passage of an amendment to the Cuban Constitution through a compliant national assembly so that he could be reelected to a new, and extended, six-year presidential term. The 1929 stock market crash soon ended the boom times, and Machado led an increasingly repressive and brutal regime, backed by the United States in exchange for stability in a country now deeply entwined with American economic interests. He dealt harshly with labor unions and authorized the torture and assassination of his political opponents, who increasingly included not only leftists and university students but the country’s educated elites.

“Machado was the cleverest politician ever produced by the island, greedy, revengeful and unscrupulous,” wrote Ruby Hart Phillips, a distinguished American journalist of the period whose husband, James, was the New York Times correspondent in Havana (she would go on to assume that job herself after his death). “But he was the result of a system of government rather than the creator of a dictatorship,” she added, noting that under Spanish rule, no Cuban had ever been granted governing authority. The country’s post-independence leaders had all been former guerrillas, “and it was inevitable that they should follow the rule by which they had lived—that to the victor belongs the spoils.” The Cuban writer and revolutionary leader Rubén Martínez Villena dubbed Machado the “asno con garras” (the “donkey with claws”), and the nickname stuck.

In Santiago, the Arnaz administration enforced its own measure of civic discipline. Mayor Arnaz himself undertook a kind of cultural repression against his city’s signature public event. On the eve of Santiago’s carnival in July 1925, the alcalde modelo condemned the distinctive African-derived line dance that to this day is the city’s defining annual ritual. “The ‘conga,’ the ‘rope’ and other similar dances full of improper contortions and immoral gestures that do not belong to the culture of the city are not and never have been manifestations of the masquerades, and conflict with their tradition,” Mayor Arnaz declared, promoting instead the more benign elements of carnival—the floats and parades and parties. “I refer to the ‘conga’ as that strident group of drums, frying pans and howling, to the sound of which epileptic, ragged, and semi-naked crowds run through the streets of our city. Between lubricious contortions and brutal movements, they disrespect society, offend the morals, cause a bad opinion of our customs, lower us in the eyes of the foreigners, and, most gravely, contaminate by example the minors of school age who are carried away by the heat of the display, and whom I have seen, painted and sweaty, engaging in frenetic competitions of bodily flexibility in those shameful wanton tournaments.” In 1929, as violence and political unrest were growing, the mayor forbade the dances outright, banning “every kind of comparsas or ‘parrandas’ that use the music of the bongo, and other similar instruments.”

In his memoir decades later, the younger Desi would not recall his father’s stern injunctions. Instead he remembered the immense, convulsive power of the conga-dancing crowds as they paraded through the streets to Cespedes Park on the plaza in front of city hall. He relished the effect that the singing and dancing, the sticks and drums and clanging upside-down frying pans, had on one of his father’s political advisers, Alfonso Menencier, a distinguished, middle-aged Afro-Cuban who was always impeccably dressed in a white linen suit and carefully knotted tie as he stood on the steps of city hall. As a raucous crowd approached the plaza one year at carnival time, Señor Menencier had more and more trouble controlling his tapping cane and itchy feet. Finally he gave in. “He could not control himself any longer, nobody could,” Desi recalled. “His collar came open and his tie undone with one fuck-it-all yank. His straw hat landed on the back of his head; with his cane high in the air, he joined them in ecstasy and so did everyone else standing on those steps, including the mayor and the American tourists and embassy guests of his.”

Desi would claim to have had little consciousness of race until he arrived in the United States. But in fact his father saw the conga as a threat to civic order in part because of Santiago’s complex racial dynamics. “Race mattered in Santiago, deeply,” Patrick Symmes has written. “It was the blackest city in the blackest region, the Afro-Cuba metropolis par excellence, but Santiago was still ruled by whites, who preferred to think of Santiago as a city with ‘easy’ or ‘warm’ relations between the races. That was only because blacks knew their separate place, and kept to it.” Country clubs, restaurants, and schools—including the Colegio de Dolores—were all segregated, and in such elite institutions, “white was the only color that counted.”

Mayor Arnaz had a personal instrument of repressive authority in maintaining public order: his brother Manuel, who was Santiago’s fearsome chief of police. “We had that town pretty well wrapped up,” Desi would crack years later. While there is no evidence that Mayor Arnaz himself was any more menacing than a local cog in the island’s political establishment—or that he was personally corrupt—the same is not so clear for Manuel, a physically huge, forbidding figure. His nephew George Rodon, who grew up in Santiago, remembers being terrified of Manuel as a child, even in the 1950s. “Oh my God, it’s scary, because politics was dirty then, and Lord knows what he did,” Rodon recalled. “I don’t assume Uncle Desi was dirty, but no one went into Cuban politics and came out poor.” Young Desi himself was well aware of the brutality of the Machado regime. In an unpublished draft of his memoir, he referred to Colonel Arsenio Artiz, the head of the Santiago branch of the Porra, the government’s notorious secret police, as “a real son of a bitch, a butcher, he liked to kill.”

Mayor Arnaz was at least acquiescent enough to the Machado regime to run successfully for Congress in 1932, leaving the mayoralty to join the national government in Havana. In the midst of that campaign, in the wee hours of February 3, a devastating earthquake struck Santiago, destroying about a third of the city’s buildings, including city hall. Desi and his mother were alone in their house on San Basilio Street—“the big beams in the open ceiling of that huge old house were dancing around like toothpicks,” he would recall—and his father, who had been at work in his office, came running home, covered with plaster and looking “like a ghost.”

In the aftermath of the quake, Desi’s father built the family a new house in the leafy, elegant suburb of Vista Alegre, on the city’s northeastern edge, which had been developed in the 1920s with spacious mansions in the Cuban eclectic architectural style for the city’s elite. The new Arnaz house—an all-wood frame, with carved columns on its front porch, the better to withstand future earthquakes—was on the neighborhood’s main boulevard, the Avenida Manduley, at the edge of a circular park named for the Cuban Romantic poet José María Heredia and just across the street from an exclusive tennis club. The Arnazes moved there in late 1932. But nothing could protect them from the shock of the political earthquake that was coming.

By the summer of 1933, despite its ever-escalating campaign of torture and repression, the Machado government was collapsing. In early August, food was scarce. Across the island, conditions were growing intolerable. “Everything is paralyzed, industries shut down, stores closed, streets deserted. On the National Highway, private cars are being fired upon,” Ruby Hart Phillips recorded.

In Santiago, Desi was in the new Vista Alegre house with his mother—his father was in Havana—on the afternoon of Saturday, August 12, when the phone rang with a call from his mother’s brother Eduardo de Acha, a prominent lawyer. “Get your mother out of the house right away!” his uncle said. “They’re coming after you!”

“Who’s coming after us?” Desi asked.

“Machado has fled the country, and anyone who belonged to the Machado regime is in danger.”

Indeed, the situation in Cuba had gotten so bad that the American ambassador, Sumner Welles, had given Machado an ultimatum to step down. Machado had taken a plane to Nassau in the Bahamas—taking with him, by Mayor Arnaz’s later firsthand account, “five guys in pajamas,” each of them “carrying two or three sacks of gold,” Desi would recall.

It seemed inconceivable to the sixteen-year-old Desi that the populace of Santiago could have turned so abruptly against the alcalde modelo, whose election to Congress they had celebrated only the previous fall. But his uncle explained that in the chaos, a motley crew of protestors and activists were bent on revenge and wreaking havoc, with the city’s Moncada military barracks in flames and the local police unable to maintain order. “Just as I hung up, I heard a rumble,” Desi would recall. “I looked out and could not believe what I saw. About eight blocks away, just beginning to come over the top of the hill on our main boulevard, there was a mob of five hundred people or more carrying torches, pitchforks, guns, and God knows what else.”

Together with the family’s Black manservant, Bombale, Desi and his mother prepared to flee to the home of Lolita’s uncle Antonio Bravo Correoso, a former senator and a leading criminal lawyer who was a political opponent of Machado. As it happens, they were driven there by Emilio Lopez, a friend who was one of the leaders of the ABC movement, an anti-Machado organization. Lopez rescued Desi and his mother when Bombale realized he had removed the battery in the Arnaz family car for repair that morning. The family hid at Lopez’s house until dark, when they headed for Bravo’s residence, passing Casa Arnaz on the way. The year-old house had been torched, though not burned to the ground, and its contents strewn all over the front garden: clothes, furniture, paintings, records, plates and glasses, sports equipment. Desi’s mother’s rosewood piano—which had belonged to her mother and grandmother before her—was smashed to pieces. Desi’s own guitar lay in splinters like a pile of kindling.

“Civilization was stripped away in one stroke,” Ruby Hart Phillips would write of that week. “Relatives of boys who had been tortured and killed started on vengeance hunts and they knew the men they were seeking.” The Arnaz farms and the family house on Cayo Smith suffered similar rampages; rioters killed the livestock, leaving it to rot, and sank the family boats. At his uncle Bravo’s house, Desi found himself in a state of shock. “For the next few days I walked around the house like a zombie,” he would remember. “I ate and I slept, I took a bath, I talked and I thought. I thought a lot. The only thing I couldn’t do was cry. I could not understand what had happened. Dad had always been loved in that town.”

Mayor Arnaz was either arrested or decided to turn himself in to Havana’s La Cabaña prison for protection. When Desi and his mother eventually made it to the capital themselves, conditions were if anything even worse there. “There was one sight I will never forget,” Desi would recall more than forty years later. “A man’s head stuck on a long pole and hung in front of his house. The rest of the body was hung two doors down in front of his father’s house.”

The fall of the Machado regime led to a series of short-lived governments in Havana from which a onetime army sergeant, Fulgencio Batista, eventually emerged as the dominant figure. For the next quarter century, in one strongman guise or another, Batista would remain a force in Cuban politics, ultimately ruling from 1952 on in a repressive regime whose brutality and corruption would pave the way for Fidel Castro’s revolution of 1959. For Desi Arnaz, the collapse of the only social, emotional, and family universe he had ever known—at the formative age of sixteen—created psychic scars that would last a lifetime. But this youthful trauma would also be forever linked with a willingness to take bold risks—and a burning, consuming drive to succeed.

He was a Pisces, born on an island, and for the rest of his life, in happy times and times of bad trouble, he would always return to the sea. He was an only child—a rarity in the Catholic culture of his time and place—a handsome, dark-eyed boy. In surviving formal photographs, he is sober, in his sailor suits and white linens, or in a pirate costume and painted mustache at an early birthday party. He looks mature beyond his years, and that is perhaps not surprising: From the beginning, Desiderio Alberto Arnaz y de Acha was raised as a prince.

He was born on March 2, 1917, in a spacious Spanish colonial house on Santa Lucia Street in Santiago de Cuba, the island’s original capital and still its second-largest city after Havana. Not twenty years earlier, Theodore Roosevelt had stormed up the San Juan Heights, on Santiago’s northeastern fringes, in the Spanish-American War. He had pronounced it a “quaint, dirty old Spanish city,” though he allowed that “it was interesting to go in once or twice, and wander through the narrow streets with their curious little shops and low houses of stained stucco, with elaborately wrought iron trellises to the windows and curiously carved balconies.” Other visitors might have likened the city’s hilly, bayside topography to San Francisco’s, and its polyglot, bon temps rouler, music-filled atmosphere to that of New Orleans. To this day, the region is known as la tierra caliente, as much for the natives’ fiery temperaments as for the high temperatures.

Situated at the head of a wide, safe harbor on the southeastern, leeward side of the island, Santiago had been settled by the Spanish in 1515; over the next three hundred years the city was successively plundered by French and English forces and a rogues’ gallery of pirates. The aftermath of the slave uprising in neighboring Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, in the 1790s brought an influx of newly freed Africans—together with fleeing slave owners and their human chattel—that created an unusually rich demographic mix, importing African musical, culinary, and cultural influences and establishing sugarcane—“white gold”—as the island’s dominant cash crop. Tobacco farming, copper mining, and fishing were Santiago’s other industries, and in 1862 the Bacardí rum distillery was founded there, spreading its signature sugar-based spirit across the Caribbean and the Americas.

“Something about Oriente invites exaggeration,” the journalist Patrick Symmes wrote of the region around Santiago. “It is the hottest part of Cuba, the most mountainous, the first settled, and the earliest to achieve glory and shame…. There were men present at the founding of the city who had known Columbus himself, and the 1515 date was so early that it rooted Santiago more in the European Middle Ages than in the new world to come. Santiago was the first capital of Cuba, reigning for forty years before eventually losing out to Havana, an insult never forgotten. The city served as a kind of Jerusalem to the Americas, spreading the new faith of conquest, and the new tongue of Castilian.”

And, Symmes continued, “white or black, poor or rich, the Santiaguero insisted with a straight face that fruit is riper, the sun is stronger, the women more passionate, the politics more sincere, the talk more profound, the cemeteries more grand, even the night darker, than elsewhere in Cuba.” Residents of Oriente “insisted that not only was Cuban music the best music in the world, which everyone already knew, but Oriente was the only source of Cuban music.”

By the time of Desi’s birth, la familia Arnaz (properly pronounced Ar-NAAS, not Ar-NEZZ, as Hollywood would later Anglicize it) was firmly established as Santiago aristocracy. The matriarch, Dolores Vera y Portes, had fled Seville with her parents in the early nineteenth century when Joseph-Napoléon Bonaparte, the emperor’s older brother, invaded Spain and exiled the family. The Vera family bought or was granted land in and around Santiago and built a hilltop villa on Cayo Smith, a tiny islet near the mouth of Santiago Bay. Dolores, an only child, would eventually marry Manuel Arnaz y Cobreces, the municipal fire chief of Santiago, who in 1869 would be appointed the city’s mayor by Queen Isabella II of Spain. (The surname Arnaz itself is of Basque origin, after the town of Arnaz in Spain; in France it is rendered Arnault and in Italy Arnaldi.) Manuel and Dolores’s only son, Desiderio Arnaz y Vera, the first Desi in the family line, was born in 1857. His family sent him back to Spain to study medicine at the University of Seville, and he returned to Santiago as a practicing physician. In 1884, he married Rosa Alberni y Portuondo, a member of the Cuban nobility descended from an old and illustrious Santiago family. (Her great-grandfather, the first count of Santa Inés, had also been mayor.) She would bear Dr. Arnaz seven children: three sons and four daughters. One of those sons, born in 1894, was also christened Desiderio, and he would become the father of the family’s third Desi, who won worldwide fame.

The first Desiderio Arnaz’s growth to maturity had coincided with the rise of the movement for Cuban independence from Spain, a drive that began in 1868 when a small plantation owner, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, freed his slaves and proclaimed Cuba a sovereign state. This sparked a ten-year war that left two hundred thousand people dead but resolved nothing—though the resulting economic disaster led for the first time to heavy American investment in Cuban real estate and agriculture. In 1886, a royal Spanish decree finally abolished slavery on the island. And in 1895, the Second War of Independence began, this time led by José Martí, a poet, journalist, and lawyer who had been an active lobbyist for the Cuban cause from his exile in the United States. Martí was killed in his first battle and is revered to this day as a national hero (both by Cubans on the island and Cubans in exile; one of the few points on which they agree). His tomb in Santiago’s Santa Ifigenia Cemetery is a shrine. In 1898, spurred on by a group of neocolonialist American politicians (including Theodore Roosevelt, who was then assistant secretary of the navy, and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts) and whipped into a frenzy by sensationalist press coverage of wartime Spanish atrocities and the mysterious sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor, the United States joined the Cuban rebels to repulse Spanish rule—and, not coincidentally, secure the U.S. economic stake in the island. (Many historians contend that the Cubans were already winning and did not need American intervention.) In any case, the effort was short and successful—a “splendid little war,” Secretary of State John Hay called it—and climaxed in the assault on the San Juan Heights outside Santiago on July 1, 1898. That cavalry charge in turn swiftly propelled Roosevelt to the governorship of New York later that year, to the vice presidency two years later, and ultimately to the presidency upon the assassination of William McKinley, in 1901.

But Cuba’s nominal independence came at a high price. The island traded its status as a Spanish colony for effective subjugation to the United States, beholden to American strategic and commercial interests. Congress passed the Platt Amendment, which was also enshrined in the new Cuban constitution, allowing the United States to intervene with military force in Cuban internal affairs as it saw fit. The next thirty years would see steadily increasing American influence and entanglement with a succession of Cuban governments, whose leadership was largely made up of veterans of the 1895–1898 war.

Arnaz family lore holds that Desiderio was attached to Roosevelt’s cavalry forces at San Juan Hill, though hard evidence is lacking. What is not in dispute is that Don Desiderio achieved the rank of captain in the Liberation Army, “obtained after bloody battles in the fields of Cuba,” as one of his obituaries would later put it, and the Arnaz dynasty became firmly entwined in the Cuban-American alliance. As a youth, the doctor’s son Desiderio II was apparently a handful, academically capable but easily distracted and too curious and querulous for the Catholic brothers who taught him. So his parents sent him off to school in America, to the small town of Sidney, New York, near Binghamton, a destination chosen for reasons that his descendants never understood. He spoke not a word of English, lived with an American family, and had a tough time of it. His family wanted him to follow his father’s career and become a physician. Instead, he eventually enrolled at the Southern College of Pharmacy in Atlanta (now part of Emory University), and in 1913 he earned the pharmacist degree that would let him style himself for the rest of his life, like his father before him, as “Dr. Arnaz.” The young Desiderio returned to Santiago, opened his own drugstore, and in 1916 married Dolores de Acha y de Socias, who had been born in the neighboring Dominican Republic in 1896 and was once declared one of the twelve most beautiful women in Latin America. Dolores, known to everyone as Lolita, gave birth to their only son the next year, and the youngest Desi would grow up in an atmosphere of unquestioned privilege. Lolita’s father, Alberto de Acha, had started as a Bacardí rum salesman, loading mules with as many bottles as they could hold and hawking his load in Santiago and the surrounding countryside. He later wound up as a vice president of the company, and when Bacardí was reorganized as a stock corporation in 1919, he received shares valued at ten thousand dollars (nearly two hundred thousand dollars in 2020s currency), a windfall that would benefit his family for decades to come.

Besides running his pharmacy, the younger Dr. Arnaz operated three farms in the countryside surrounding Santiago, one of them raising beef, another a dairy farm, and a third producing poultry and pork, with an accompanying slaughterhouse. (A Desilu corporate press release would later claim the family’s holdings amounted to one hundred thousand acres, but that may have been Hollywood hype.) These extensive enterprises evidently did not scratch every itch, and in 1923 Desiderio II followed in his grandfather Manuel’s footsteps, becoming mayor of Santiago, at age twenty-nine the youngest in the city’s history. In his case, however, the office came not by royal appointment but after a vigorous election campaign in which he ran on a reform platform of improving the city’s public works and infrastructure, a program that would eventually lead to his reputation as el alcalde modelo, the model mayor. Arnaz put management of his pharmacies in the hands of employees and set about remaking his hometown, which lacked a reliable water supply, adequate sanitation, and paved streets.

He built parks and a municipal swimming spa, installed the city’s first traffic light, inaugurated the first radio telegraph service, celebrated the creation of an airfield by Pan American Airways, and greeted a visiting Charles Lindbergh in 1929. But his crowning achievement was the restoration of the crumbling alameda on the city’s waterfront, where he built graceful welcoming arches, a seawater swimming pool, a wide park, and a striking clock tower, which the local chamber of commerce dedicated in his honor. The alameda opened in 1928 with a parade and the crowning of a queen, escorted by the eleven-year-old Desi III, “the simpatiquísimo son of our Municipal Mayor, who will be the representative of his popular father in this simpatico event,” as one local newspaper put it.

“I don’t rest,” a contemporary newspaper quoted el alcalde modelo as saying. “I am always running at a trot.” But, he added, he was ecstatic at the public’s support. “I am convinced that all we need here is initiative…. It is possible you think me crazy, but I think to pull Santiago out of the miserable situation that exists—ruined and forgotten—we have to do some crazy acts, and I will do them.”

As the only son of Santiago’s most influential citizen, Desi III reaped the benefits and bore the high expectations that came with such stature. In a family scrapbook kept by Mayor Arnaz, there are pictures of little Desi, always meticulously dressed and groomed. In one, he is decked out as a swarthy buccaneer, surrounded by a gang of similarly outfitted boys and girls at his birthday party, when he appears to be about six or seven. “Desi, always social, with more friends than anyone else,” his father noted in the caption. In another photograph from the same time, Desi holds a checkered starter’s flag and, looking slightly frightened, stands surrounded by a raft of boys in small racing cars, ready to judge a soapbox derby in Cespedes Park, the city’s central square, facing the Santiago Cathedral and city hall. Mayor Arnaz’s caption combines parental pride and fatherly ego: “He was always a leader, as I taught him to be.”

Indeed, young Desi was taught to take his place among the island’s elite, and discipline was expected. In summers, in the country, he rose at dawn with other farmhands to milk cows and perform chores. For as long as he could remember, he rode a horse well and herded cattle; for his tenth birthday, he received a fine Tennessee walking horse. He was responsible for earning his own spending money. But from the beginning, there was also a touch of the devil in the boy, and he was more than a little spoiled. When he was four, with his family now living in a larger gray stucco colonial house in San Basilio Street, directly across from his Arnaz grandparents and about four blocks from city hall, Desi tried using the drawers of his father’s bedroom chiffonier as steps “to reach a lovely pearl-handled revolver I knew he kept in the first drawer from the top, safely out of my reach, or so he thought. I was grabbing the revolver when the chiffonier tumbled forward, pinning me under and cutting a deep gash in my chin and head while simultaneously causing the revolver to fire and scaring the hell out of me.” The bullet struck an antique cuckoo clock, which proceeded to chirp frantically as his nanny rushed in and extricated him and took him across the street, where his grandfather the doctor stitched him up with a needle and thread.

On San Basilio Street, his house was forbidding from the outside, with heavy wooden shutters and wrought-iron bars at the windowed facade. But the thick old walls made the home cool and shaded inside, and there was a gracious interior garden courtyard open to the sky and a front porch with rocking chairs facing the street. Mosaic tile covered the floor of the living room, which featured a plush sofa and chairs and an oil painting of Desi and his parents. Old-fashioned brass lamps shed gentle light, and a “monstrous French player piano” that no one in the family could play added an elegant touch, Arnaz’s childhood friend Marco Rizo would recall. Desi would have grown up listening to the sounds of streetcars running down the middle of the cobblestoned avenues and the cries of street vendors hawking everything from peanuts to produce to household goods. He would have smelled the scent of horses, which were still a common means of daily transportation and commerce in his childhood. And, always and everywhere, he would have heard music, which streamed across the city day and night. “Music was something we both ate, drank, and bathed in from birth,” Rizo recalled. Desi’s uncle Eduardo de Acha played the guitar, sang, and composed songs, and another uncle, Rafael de Acha, was also musical. Somewhere along the way, Desi himself learned to play the guitar, but he never learned to read music, though he did take a few lessons from Don Alberto Limonta, an Afro-Cuban who taught many of the city’s privileged sons. “No, he wasn’t a prodigy who could play a Brahms concerto on an instrument by the age of four,” Rizo recalled, “but he definitely stood out as an appreciator of anything musical from childhood on.”

Desi’s favorite place by far was his family’s summer home on Cayo Smith. The cayo, or key, was a small island at the mouth of Santiago Bay, perched just below El Morro, the rockbound Spanish fort that guarded the entrance to the harbor. Named for the wealthy British slave trader who had once owned it, el Cayo rose from the blue Caribbean like “a little mountain coming out of the water,” Desi would remember decades later. The island was ringed with fishing boats, crested with a white hilltop church, and dotted with wooden “bungalows”—actually, spacious vacation retreats for the city’s elite. There were no cars or streets, and an energetic teenager could circle the little island’s perimeter in no more than forty-five minutes on foot. Desi and his friends often swam around it instead. It was also the scene of an adolescent misadventure more embarrassing than Desi’s climb up his father’s dresser.

Casa Arnaz, perched on a hill and with polished hardwood floors and shuttered windows, opened onto a seventy-five-foot pier with a two-slip boathouse, berthing the sleek speedboat that took Desi’s father to work at city hall each morning and Desi’s own eighteen-foot, wooden Norwegian fishing skiff. It was in one of the dressing rooms of that boathouse, still ignorant of the facts of life at age twelve, that the boy undertook to learn. His co-conspirator was the same age, the daughter of his family’s Black cook. “After locking the door, we began to experiment about how this thing was done,” he would recall. “Neither of us had the slightest idea… but I was obviously anxious and noticeably ready for action and getting more and more frustrated by the minute. We had tried a number of ridiculous experiments and were working on a new one when there was a loud knock on the door. It was her mother the cook, asking her to come out. I didn’t have any trouble putting on my trunks in a hurry. The small proof of my anxiety had disappeared. I wish I could have done the same.”

Frantic to escape, Desi dove out a high window straight into the water below and swam as long as he could under the surface to a neighboring pier, where he heard his uncle Salvador, his father’s younger brother, calling out: His mother had seen the whole tableau in pantomime. That night, Desi’s father took him into his study and let him have it. “Have you ever seen me insult your mother?” Mayor Arnaz demanded. “Have you ever seen me embarrass her or make her ashamed of me?… You listen to me, young fellow, and listen good. Don’t you ever insult your mother that way again or embarrass her as you did. Now get the hell out of here.”

In an unpublished draft of his memoir decades later, Desi would reflect, “I thought in later years it was really very nice of my dad to treat the incident that way, because the wrong kind of approach at that time would have probably made me awful scared of sex and ashamed of having to find out about it. But he put it on the basis of being a gentleman and respecting your mother. If you’re going to do that thing, do it privately and not in front of your house.” Alas, this was a lesson that Desi, man and boy alike, seemed destined to never quite learn.

Desi’s sexual education culminated three years later, at fifteen, when his uncle Salvador, who owned a small soap factory, took him to Casa Marina (“the finest whorehouse in Santiago,” Desi would recall), which featured live music, elegant parlors, and an elite clientele. Desi assumed that the outing had come at the direction of his father, and there in the deluxe bordello “I learned the whole deal,” as he would later put it, from “ladies of the house” who were “all young and clean and treated me very kindly, very nicely, very tenderly, and very expertly. Sometimes I wonder if perhaps it is not better to educate a young boy like that instead of letting him get into a lot of trouble trying to find out for himself.”

In fact, this formative experience would cause Desi plenty of trouble in future years, because he had internalized the mixed messages about sex and gender reflected in the patriarchal, chauvinist Latin culture in which he was raised. On the one hand, sex with whores was there for the asking while nice women, respectable women—like his mother, elegant and aloof—were to be treated with courtesy extending to gallantry. On the other hand, the society of his class and time subjugated even such respected women to second-class, subordinate roles and a cruel double standard: Men could stray sexually, unpunished; women could not. Desi’s grandfather Arnaz kept a casa chica, a second home with his mistress and multiple illegitimate children, on a small farm in El Caney north of Santiago. Marco Rizo recalled that Mayor Arnaz also “kept himself satisfied with two longstanding private relationships with women outside his marriage,” a reality known to Santiago society but apparently not to Lolita. When Desi’s grandfather, a non-churchgoer, was dying, his wife implored her grandson to bring a priest to pray with Dr. Arnaz. “Ponga el corazon con Dios” (“Put your faith in God”), the priest counseled. “Ponga el corazon con Dios y el rabo tiezo” (“Put your faith in God and a stiff prick”), Grandfather Arnaz replied.

Desi would struggle throughout his life to make sense of these dichotomies. “I got very mad at my father sometimes,” he would recall decades later. “I was the only son, and due to his job, or whatever the hell it is, he wouldn’t be home until late, and everything else, and my mother used to adore this guy and her whole life was him and I used to say to her, ‘What the hell? What is this with you?’ you know. ‘You’re like a slave to this guy. You treat him like he’s a goddamn king or something.’ My mother said something that I’ll never forget. She said, ‘Yeah, that’s true, I treat him like a king.’ I said, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘That’s the only way I can be a queen.’?”

Indeed, by all accounts, Dolores de Acha went through life with a regal air and was a difficult, domineering woman. “Lolita came from a very privileged level of society in Cuba,” Lucille Ball’s cousin Cleo Smith, who came to know her in later years, would recall. “I mean, you have help by the dozens, and never lifted a finger, and never learned to cook, and you never did a bit of housework, you never did anything.” The longtime Ball-Arnaz family friend Marcella Rabwin was more succinct: “Lolita was impossible for anyone to love.”

Of Mayor Arnaz himself, another family member would recall, “He didn’t like people that weren’t sincere. He wanted everything to be just right, no deviation from the way things should be.” Rabwin would remember, “There was a certain egotism in Dr. Arnaz,” and after Desi III became world famous, his father “did not want Desi, in his great importance, to be more important than he had been. There was a sort of rivalry thing there. Desi didn’t really feel it, but I think the father did, because he wouldn’t let Desi have the last word. If they were talking and there was any slight difference of opinion, Dr. Arnaz prevailed.” Decades later, Desi’s daughter, Lucie, who witnessed her father’s interactions with her grandparents as a young adult, would judge that Desi had lacked the deepest sort of parental nurturing and emotional support. “The mother-father strange relationship that never really was embracing, never really was loving, never was unconditional,” she said. “It was always, ‘You have to prove yourself…. You’re not enough if I don’t have enough,’ and that’ll kill you, you know.”

In his own memoir, Desi would recall his father’s blend of sternness and indulgence. Desi’s high school was the rigorous Colegio de Dolores, led by the Jesuit order, where a decade later a boy from the provinces named Fidel Castro would also be a student. “Neither an overt rebel nor a dreamer,” Marco Rizo would recall, Desi “was always a person of action.” When he was a teenager, his parents gave him a car, and he drove around “with as many girls as he could fit in it,” Rizo said.

In his junior year of high school, Desi realized to his chagrin that he was about to fail geometry and trigonometry and would not be able to pass his final exams—a potential crisis for a student who aspired to attend college in the United States (he and his parents often spoke of sending him to Notre Dame, a storied Catholic school and football powerhouse) and then law school. “So, what do you want from me?” Mayor Arnaz demanded when Desi gave him the news. “I’m sorry, Dad, I don’t know what happened,” the son explained, and the father retorted, “I know what happened. You discovered girls, and from the report I got from my soap-making brother, you didn’t have any trouble learning that subject.” Still, the mayor agreed to help out, dispatching a police sergeant on the Palacio Municipal detail, who was a whiz at math, to tutor Desi privately.

In March 1933, when Desi turned sixteen, his father wrote him a letter of advice that he would keep for the rest of his life. “You are now sixteen, and in my book, that means you are no longer a child; you are a man,” Mayor Arnaz wrote. He warned his son that life was like the road from Santiago to the family’s farm in nearby El Cobre, sometimes smooth and beautiful, sometimes ugly and rough. “Remember, good things do not come easy, and you will have your share of woe—the road is lined with pitfalls. But you will make it, if when you fail, you try and try again. Persevere. Keep swinging.” It was timely advice. Desi’s father might have had some inkling of just how much that counsel would be needed in the months and years ahead, because by 1933 the Cuban political and social establishment that the senior Arnaz had thrived in was falling to pieces—into violence, repression, and turmoil.

Mayor Arnaz’s political career had coincided with the rise of Cuba’s most powerful figure, President Gerardo Machado. One of the youngest generals in the Cuban War of Independence, Machado had aligned himself in the 1910s with liberal forces opposing the American-backed regime. He won office in 1924 as the Liberal Party candidate, campaigning on a platform of “water, roads, and schools.” He pledged to serve only one term and to seek abrogation of the Platt Amendment allowing American intervention in Cuban political affairs. He undertook an ambitious plan of public works, winning the support of local officials beholden to him. His efforts were responsible for the National Highway that stretches across the entire island and the Hotel Nacional in Havana. The hotel quickly became a deluxe destination for the American tourists who had been flooding to Cuba since the advent of Prohibition in 1920, a phenomenon celebrated by Irving Berlin in his song “I’ll See You in C-U-B-A,” which promised a rum-soaked paradise where “dark-eyed Stellas light their fellers’ panatelas.”

Sugar production thrived, American investors prospered, and Cuba became known as “the Switzerland of the Americas.” But soon enough, Machado waffled on his pledge to overturn the Platt Amendment and reneged on his promise to serve just one term, running again, this time unopposed, in 1928 (with the acquiescence of President Calvin Coolidge) and forcing passage of an amendment to the Cuban Constitution through a compliant national assembly so that he could be reelected to a new, and extended, six-year presidential term. The 1929 stock market crash soon ended the boom times, and Machado led an increasingly repressive and brutal regime, backed by the United States in exchange for stability in a country now deeply entwined with American economic interests. He dealt harshly with labor unions and authorized the torture and assassination of his political opponents, who increasingly included not only leftists and university students but the country’s educated elites.

“Machado was the cleverest politician ever produced by the island, greedy, revengeful and unscrupulous,” wrote Ruby Hart Phillips, a distinguished American journalist of the period whose husband, James, was the New York Times correspondent in Havana (she would go on to assume that job herself after his death). “But he was the result of a system of government rather than the creator of a dictatorship,” she added, noting that under Spanish rule, no Cuban had ever been granted governing authority. The country’s post-independence leaders had all been former guerrillas, “and it was inevitable that they should follow the rule by which they had lived—that to the victor belongs the spoils.” The Cuban writer and revolutionary leader Rubén Martínez Villena dubbed Machado the “asno con garras” (the “donkey with claws”), and the nickname stuck.

In Santiago, the Arnaz administration enforced its own measure of civic discipline. Mayor Arnaz himself undertook a kind of cultural repression against his city’s signature public event. On the eve of Santiago’s carnival in July 1925, the alcalde modelo condemned the distinctive African-derived line dance that to this day is the city’s defining annual ritual. “The ‘conga,’ the ‘rope’ and other similar dances full of improper contortions and immoral gestures that do not belong to the culture of the city are not and never have been manifestations of the masquerades, and conflict with their tradition,” Mayor Arnaz declared, promoting instead the more benign elements of carnival—the floats and parades and parties. “I refer to the ‘conga’ as that strident group of drums, frying pans and howling, to the sound of which epileptic, ragged, and semi-naked crowds run through the streets of our city. Between lubricious contortions and brutal movements, they disrespect society, offend the morals, cause a bad opinion of our customs, lower us in the eyes of the foreigners, and, most gravely, contaminate by example the minors of school age who are carried away by the heat of the display, and whom I have seen, painted and sweaty, engaging in frenetic competitions of bodily flexibility in those shameful wanton tournaments.” In 1929, as violence and political unrest were growing, the mayor forbade the dances outright, banning “every kind of comparsas or ‘parrandas’ that use the music of the bongo, and other similar instruments.”

In his memoir decades later, the younger Desi would not recall his father’s stern injunctions. Instead he remembered the immense, convulsive power of the conga-dancing crowds as they paraded through the streets to Cespedes Park on the plaza in front of city hall. He relished the effect that the singing and dancing, the sticks and drums and clanging upside-down frying pans, had on one of his father’s political advisers, Alfonso Menencier, a distinguished, middle-aged Afro-Cuban who was always impeccably dressed in a white linen suit and carefully knotted tie as he stood on the steps of city hall. As a raucous crowd approached the plaza one year at carnival time, Señor Menencier had more and more trouble controlling his tapping cane and itchy feet. Finally he gave in. “He could not control himself any longer, nobody could,” Desi recalled. “His collar came open and his tie undone with one fuck-it-all yank. His straw hat landed on the back of his head; with his cane high in the air, he joined them in ecstasy and so did everyone else standing on those steps, including the mayor and the American tourists and embassy guests of his.”

Desi would claim to have had little consciousness of race until he arrived in the United States. But in fact his father saw the conga as a threat to civic order in part because of Santiago’s complex racial dynamics. “Race mattered in Santiago, deeply,” Patrick Symmes has written. “It was the blackest city in the blackest region, the Afro-Cuba metropolis par excellence, but Santiago was still ruled by whites, who preferred to think of Santiago as a city with ‘easy’ or ‘warm’ relations between the races. That was only because blacks knew their separate place, and kept to it.” Country clubs, restaurants, and schools—including the Colegio de Dolores—were all segregated, and in such elite institutions, “white was the only color that counted.”

Mayor Arnaz had a personal instrument of repressive authority in maintaining public order: his brother Manuel, who was Santiago’s fearsome chief of police. “We had that town pretty well wrapped up,” Desi would crack years later. While there is no evidence that Mayor Arnaz himself was any more menacing than a local cog in the island’s political establishment—or that he was personally corrupt—the same is not so clear for Manuel, a physically huge, forbidding figure. His nephew George Rodon, who grew up in Santiago, remembers being terrified of Manuel as a child, even in the 1950s. “Oh my God, it’s scary, because politics was dirty then, and Lord knows what he did,” Rodon recalled. “I don’t assume Uncle Desi was dirty, but no one went into Cuban politics and came out poor.” Young Desi himself was well aware of the brutality of the Machado regime. In an unpublished draft of his memoir, he referred to Colonel Arsenio Artiz, the head of the Santiago branch of the Porra, the government’s notorious secret police, as “a real son of a bitch, a butcher, he liked to kill.”

Mayor Arnaz was at least acquiescent enough to the Machado regime to run successfully for Congress in 1932, leaving the mayoralty to join the national government in Havana. In the midst of that campaign, in the wee hours of February 3, a devastating earthquake struck Santiago, destroying about a third of the city’s buildings, including city hall. Desi and his mother were alone in their house on San Basilio Street—“the big beams in the open ceiling of that huge old house were dancing around like toothpicks,” he would recall—and his father, who had been at work in his office, came running home, covered with plaster and looking “like a ghost.”

In the aftermath of the quake, Desi’s father built the family a new house in the leafy, elegant suburb of Vista Alegre, on the city’s northeastern edge, which had been developed in the 1920s with spacious mansions in the Cuban eclectic architectural style for the city’s elite. The new Arnaz house—an all-wood frame, with carved columns on its front porch, the better to withstand future earthquakes—was on the neighborhood’s main boulevard, the Avenida Manduley, at the edge of a circular park named for the Cuban Romantic poet José María Heredia and just across the street from an exclusive tennis club. The Arnazes moved there in late 1932. But nothing could protect them from the shock of the political earthquake that was coming.

By the summer of 1933, despite its ever-escalating campaign of torture and repression, the Machado government was collapsing. In early August, food was scarce. Across the island, conditions were growing intolerable. “Everything is paralyzed, industries shut down, stores closed, streets deserted. On the National Highway, private cars are being fired upon,” Ruby Hart Phillips recorded.

In Santiago, Desi was in the new Vista Alegre house with his mother—his father was in Havana—on the afternoon of Saturday, August 12, when the phone rang with a call from his mother’s brother Eduardo de Acha, a prominent lawyer. “Get your mother out of the house right away!” his uncle said. “They’re coming after you!”

“Who’s coming after us?” Desi asked.

“Machado has fled the country, and anyone who belonged to the Machado regime is in danger.”

Indeed, the situation in Cuba had gotten so bad that the American ambassador, Sumner Welles, had given Machado an ultimatum to step down. Machado had taken a plane to Nassau in the Bahamas—taking with him, by Mayor Arnaz’s later firsthand account, “five guys in pajamas,” each of them “carrying two or three sacks of gold,” Desi would recall.

It seemed inconceivable to the sixteen-year-old Desi that the populace of Santiago could have turned so abruptly against the alcalde modelo, whose election to Congress they had celebrated only the previous fall. But his uncle explained that in the chaos, a motley crew of protestors and activists were bent on revenge and wreaking havoc, with the city’s Moncada military barracks in flames and the local police unable to maintain order. “Just as I hung up, I heard a rumble,” Desi would recall. “I looked out and could not believe what I saw. About eight blocks away, just beginning to come over the top of the hill on our main boulevard, there was a mob of five hundred people or more carrying torches, pitchforks, guns, and God knows what else.”