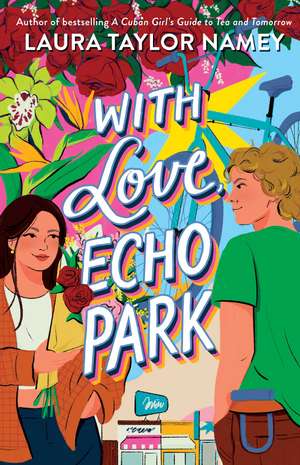

With Love, Echo Park

Autor Laura Taylor Nameyen Limba Engleză Hardback – 27 aug 2024 – vârsta până la 17 ani

Seventeen-year-old Clary is set to inherit her family’s florist shop, La Rosa Blanca—one of the last remnants of the Cuban business district that once thrived in Los Angeles’s Echo Park neighborhood. Clary knows Echo Park is where she’ll leave a legacy, and nothing is more important to her than keeping the area’s unique history alive.

Besides Clary’s florist shop, there’s only one other business left founded by Cuban immigrants fleeing Castro’s regime in the sixties and seventies. And Emilio, who’s supposed to take over Avalos Bicycle Works one day, is more flight risk than dependable successor. While others might find Emilio appealing, Clary can see him itching to leave now that he’s graduated, and she’ll never be charmed by a guy who doesn’t care if one more Echo Park business fades away.

But then Clary is caught off guard when an unexpected visitor delivers a shocking message from someone she thought she’d left behind. Meanwhile, Emilio realizes leaving home won’t be so easy—and Clary, who has always been next door, is who he confides in. As the summer days unfold, they find there’s something stronger than local history tying them together.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 48.34 lei 21-33 zile | +0.00 lei 6-12 zile |

| Atheneum Books for Young Readers – 20 noi 2025 | 48.34 lei 21-33 zile | +0.00 lei 6-12 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 70.21 lei 21-33 zile | |

| Atheneum Books for Young Readers – 27 aug 2024 | 70.21 lei 21-33 zile |

Preț: 70.21 lei

Preț vechi: 90.68 lei

-23%

Puncte Express: 105

Preț estimativ în valută:

12.43€ • 14.52$ • 10.79£

12.43€ • 14.52$ • 10.79£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 30 ianuarie-11 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781665915366

ISBN-10: 1665915366

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: f-c jacket (coated; sfx: gritty matte, emboss, gloss)+5 b-w int spot art; digital

Dimensiuni: 151 x 217 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Atheneum Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 1665915366

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: f-c jacket (coated; sfx: gritty matte, emboss, gloss)+5 b-w int spot art; digital

Dimensiuni: 151 x 217 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

Laura Taylor Namey is the New York Times and internationally bestselling author of young adult fiction including Reese’s Book Club pick A Cuban Girl’s Guide to Tea and Tomorrow, A British Girl’s Guide to Hurricanes and Heartbreak, When We Were Them, and With Love, Echo Park. A proud Cuban American, she can be found hunting for vintage treasures and wishing she was in London or Paris. She lives in San Diego with her husband and two children. Visit her at LauraTaylorNamey.com.

Recenzii

★ “Expertly rendered characters and pitch-perfect interactions coalesce into a touching and emotionally satisfying novel by Namey (A British Girl’s Guide to Hurricanes and Heartbreak) in which a small Cuban community forefronts love, unity, and support to navigate the consequences of secrets and the endless possibilities of the future.”

“Clary evolves from a high school girl clinging to her hometown and way of life to imagining a world beyond the city’s borders. . . . Cuban culture and Spanish are sprinkled throughout, adding dimension and authenticity to the story. . . . A great addition to realistic fiction, this book has equal parts romance and family drama.”

“Namey crafts deep, complex characters with rich relationships, both to their families by blood and the greater sense of familia that residents of the close-knit neighborhood of Echo Park have. . . . Set against this tight weave of history, family, and belonging, Namey’s multi-dimensional characters, pitch-perfect dialogue, and big, personal questions about identity and belonging make this an ode to family, community, culture, and friendship.”

“A satisfying blend of romance, social activism, and deep roots. . . . This earnest coming-of-age story is a tribute to family, culture, and resilience.”

“Clary evolves from a high school girl clinging to her hometown and way of life to imagining a world beyond the city’s borders. . . . Cuban culture and Spanish are sprinkled throughout, adding dimension and authenticity to the story. . . . A great addition to realistic fiction, this book has equal parts romance and family drama.”

“Namey crafts deep, complex characters with rich relationships, both to their families by blood and the greater sense of familia that residents of the close-knit neighborhood of Echo Park have. . . . Set against this tight weave of history, family, and belonging, Namey’s multi-dimensional characters, pitch-perfect dialogue, and big, personal questions about identity and belonging make this an ode to family, community, culture, and friendship.”

“A satisfying blend of romance, social activism, and deep roots. . . . This earnest coming-of-age story is a tribute to family, culture, and resilience.”

Descriere

In the latest novel by the bestselling author of A Cuban Girl's Guide to Tea and Tomorrow, the teen heirs to the last two Cuban businesses in LA's Echo Park neighborhood clash over their different visions for the future, the secrets between their families...and the sparks flying between them.

Extras

Chapter One

![]()

One

Clary (Salvia sclarea): The clary or clary sage is a flowering plant native to the northern Mediterranean Basin, along with some areas in North Africa and Central Asia. The plant has a long history as a medicinal herb and is now grown all over the world for its essential oil.

When I tell people I work with dying things, I’m only joking. For a brief stretch of beautiful, though, picked flowers appear deceptively alive. Days for most, weeks for some. I get them during this small pocket. I trim ends and strip thorns, arranging them into the kind of art that only lasts in photos. Or if you have a family like mine—maybe a Cuban abuela like Mamita—you keep them mummified, their afterlives shriveled brown. Throw away your quinceañera bouquet or your homecoming boutonniere before your abuelita or mami enshrines it? Why would you ever want to invite the wrath of an elder Latina?

Day-old tulips are the worst. If not properly prepped, their bulbous heads bend lower and lower until they’re kissing tabletops and dropping bits of black pollen. This afternoon, the arrangement on my counter features no tulips. I call this one Sunset Echo, both for the area of central Los Angeles where we live and work, and for the colors: an upward spray of roses imitating a Malibu sky before dusk. As a base, I lined the rim of a canister with a circle of white hydrangeas and a layer of apple-green cymbidium orchids and Hypericum berries.

“Oye, paging Clary Delgado, thief of my favorite denim shirt!” Lourdes calls from the rear loading bay.

My friend appears as I place a coral rose in one of the most expensive arrangements available at La Rosa Blanca, my family’s florist shop. “For the millionth time, it wasn’t me.” I add one last sprig of berries.

“Wow, fancy.” Lourdes updates her delivery tablet. “Wait, that’s for Jody Ramirez on Russell? I was just there last week. Her dude’s totally cheating.”

“Lulú!” Her nickname darts off my tongue. I said what I said is written plainly across her face. “Yeah, well, this is his third order this month. The word sorry’s been on every card.”

“Mm-hmm,” she says. “And he picked Sunset E? Spendy. He’s busted.”

Also waiting for lucky recipients are four smaller arrangements. Lourdes carts those out while I pack the container for the short drive from Echo Park to Los Feliz.

When our junior year at Silver Lake Charter School ended three weeks ago, Lourdes joined our delivery team for some summer cash. Four days a week, she drives one of the La Rosa Blanca vans around Greater LA, transporting standing orders for hotels and restaurants and “I’m sorry for whatever reason this time” arrangements.

I tuck the customer’s message into the box. There’s something about these little flat cards I’ve always loved—that it doesn’t take an overblown word dump to make a big impact. Our most popular dedication is a simple Thinking of you. Perfect.

My friend returns, her lashes fluttering with the promise of a little neighborhood chisme. I keep floral dedications confidential, but this is Lourdes Colón, my trusted ally since fifth grade. “Okay, okay. Today it’s ‘Sorry, babe. Sunnier days ahead,’?” I quote from memory.

Lourdes snorts dramatically. At five-four, she stands two inches shorter than me, but her hair is another something. Waist-long and asphalt black, it acts like our personal life gauge. Feeling flushed, or is it only the weather? Consult Lulú’s hair, which swells in high humidity. In SoCal’s nonexistent fall season, her locks flat-iron themselves and track the Santa Ana wind as well as any scientific instrument. Sometimes, she’ll gather the whole mass forward and hide behind it like a curtain. Do not disturb. I respect the hair.

“Me voy,” Lourdes says, and grabs the box. “Oh, your abuelo just finished the frame for Señor Montes’s funeral cross.” Her face dims as she backs away. “It’s in the back when you’re ready.”

My next breath hitches. Señor Montes. It’s been two weeks since we learned our beloved eighty-nine-year-old community leader checked into the hospital (for what, we still don’t know) and never came home. Salvador Montes held me as a baby and watched over so many of us local kids. A fierce Echo Park advocate, he was never too far from his friends, a cafecito, and a Cuban domino set.

I find the huge cross-shaped wreath frame Abu made—ready for my floral design—and can’t help the fall into pure memory. At the forefront, there’s the jovial Señor Montes stopping by the shop on his afternoon walk after I arrived from school. Every time, I’d take a single scrap bloom and pin it to his lapel. Now, with his memorial two days away, I have to form a hundred flowers into something worthy enough for goodbye. And for the first time since I began working here as a kid, I don’t know how to start.

Hissing and crackling sounds from the two-way radio; I leave the cross and my design sketchbook for now.

“Rose Two here,” Lourdes announces over the airways. “We have a situation. I repeat, a situation. Over.”

Lulú finds too much amusement in the delivery van communication system. She’s the one who named the three La Rosa Blanca vehicles in order of size. Rose Two is our midsize cargo van. I grab the radio. “What situation?”

“You didn’t say ‘over.’?”

Way too much amusement. “Just tell me.” Ugh, Lourdes. “Over.”

“I’m stuck. There’s a big truck blocking the driveway and tons of bikes in the way. Over.”

The culprit’s no great mystery. Our historic storefront faces bustling Sunset Boulevard, but our corner property also has a fenced rear lot where we construct floral installations and park the vans. The gated driveway is directly across the street from the side wall of Avalos Bicycle Works. Their shop faces Sunset, too, but they don’t have any loading space.

“On it,” I announce.

Outside, I hang a right and march around the side street we share with the bike shop. Lourdes waves from the window of Rose Two. Sure enough, the truck is using our property to unload, but no one’s around. The driver locked a group of road bikes to our gate with one long tether right in front of the exit. Resourceful.

I wedge the radio into my jeans pocket and send a text to Emilio.

Me: I’m assuming that the truck and bikes outside have something to do with you guys?

Emilio: Racing team dropping them off for maintenance

Me: And blocking our driveway

Emilio: Is this the flower shop owner’s version of get off my lawn?

I glare at the phone, wishing that instead of a talking bubble, it was Emilio Avalos’s tanned, angular face. I need him to see my glare.

Since we were kids with neighboring everything, there’s been an ongoing bout of strategic play between us, like a living version of the domino game Señor Montes played daily. It varies, but just as in dominoes, winning between Emilio and me usually amounts to who can outsmart the other. Or out-annoy. After years of practice, we’ve gotten good at doling out comeback quips like those little ivory tiles with black dots. We know when to play them.

Get off my lawn? Cute. Like Abu has ever yelled that from our kitchen window.

Me: We can provide you with some excellent landscape maintenance references. Meanwhile, Lourdes has DELIVERIES

Emilio: My lawn is perfectly trimmed, thank you

Emilio: Yeah, yeah we’re coming

Moments later, Emilio strides out of Avalos Bicycle Works, followed by his dad and a couple workers from their repair department. The driver jogs up to the cab and proceeds to move forward, and the guys unlock the chained-up bikes.

Emilio’s expecting annoyance, so I unclench my jaw and try to appear extra calm. Underneath, there’s a brisk pull of adrenaline. “Feel free to move the truck back after Lourdes leaves,” I offer with great diplomacy.

“Cool. But why didn’t she just call me or Papi?” Emilio asks. “Lourdes needs you out here playing traffic guard, Thorn?”

He’s called me this for years, maintaining that a girl who spends half her day stripping roses of their one painful flaw, and the other half aggravating him, deserves such a moniker. If I’m being honest, I’ve never minded the Thorn nickname. But I’ll never let him know that.

Dropping my own nickname for Emilio now would seem too predictable. “You’d rather deal with a ragey Puerto Rican than me?”

Rage might be stretching things. One glance pegs Lulú as way too entertained watching my exchange with Emilio, chin perched on folded arms over her rolled-down window.

“It’s funny you think you’re the safer bet.” Emilio grins infuriatingly.

The horn beeps twice; with her path finally cleared, Lourdes rolls away with a cheerful wave.

“A-ny-way,” Emilio says. “The driver came in asking for help unloading, but he saw this new mountain bike, and Papi and I got carried away with the specs for a minute. Sweet ride.”

“If you say so.”

His eyes twitch with perplexity—the kind where he has to rewind what I’ve said to see whether or not he should be offended. Half a second later, he pivots toward Sunset Boulevard. “Wait, Varadero Travel closed?”

I nod, wincing at the darkened windows and boarded entrance. “As of today.” Another founding piece of Cuban Echo Park is gone, just like that.

Emilio crosses his arms loosely; they’re carrying twice as many grease stains as his gray T-shirt. “Hopefully she’ll find some cheaper digs off Sunset.”

“Why should she have to, though? Ana’s parents started that agency. Right there.”

“It’s sad, but what can we do? Times change. What if we’re supposed to let the neighborhood move the way it moves?”

Move? How fitting. But this issue is about more than Emilio’s habit of sitting near doorways and hovering under exit signs. “Our businesses started at the same time as Varadero. You’re okay with more Cubans losing a big part of who we are?” I press. “Do you think Señor Montes would’ve been down with that take after he devoted his life to Echo Park?”

Emilio lets out a thick exhale. “Listen, you know I loved that guy. And our history is a great thing.” He motions to the fence where the bikes were chained. “But our past isn’t made of links that lock for good. I don’t understand why we have to be so massively tethered to it.”

My mouth drops. “Tethered? Try grounded to everything we came from.” I motion across the street to the former travel agency. Its side wall mural with two macaws flanking a slice of Cuba’s Varadero Beach adds big Latino vibes to that corner. But now… “I can’t believe the building sold to Hole Punch Donuts.”

Emilio studies the pavement. Twists his jaw.

“What? What do you know?”

“That they make ridiculously good donuts.”

Nice try, Avalos. I cough, sharpening my stare.

“Okay, okay,” he says. “I knew Hole Punch was gonna open somewhere on Sunset. About a year ago, they posted for people to suggest new locations, and I said that Echo Park needed a shop. Then there were a couple DMs. The CEO saw that my family owns a business around here, and he reached out.”

“Oh my God, this is your doing?” I jab a finger, narrowly missing his chest.

“Seriously?” Emilio pantomimes devil horns on his head. “You think I got up one day jonesing for a donut and thought, ‘Hey, what sweet, respected Cuban and their business can I personally boot off Sunset today?’?”

I square my stance. “I didn’t say that. I said you had a part in the sale.”

“Not like you mean! I made a general suggestion. How could I possibly know they’d buy Ana’s whole building? All I wanted was a double cream glazed.”

“But you just said they—” Oh, he totally said, but my head is now a trash bin of confusion and runaround. “All I’m saying is you seem to care more about your sugar fix and something shiny going in than the cost. Or Ana. Or Echo Park history and…” I rattle my head back and forth.

“And we’re back to the start,” he says. “Surprise, surprise.”

“Hey, pequeño, phone call!” Dominic waves from the bike shop entrance. At six-one, there’s nothing pint-size about Emilio. But Dominic Trujillo’s rank as Emilio’s bestie and repair department whiz lets him get away with tons.

“So, that’s me,” Emilio says.

“Yup.”

But he doesn’t turn. We’re just standing here.

A few seconds pass before he powers back on with a twitch and struts away. The atmosphere feels lighter with him gone—even though this is hardly the first time I’ve argued with Emilio or challenged him about giving up on our shared heritage and our place here. Today, the threat is too close—only a few strides across Sunset. And coming right off Señor Montes’s death, it feels too personal.

Air leaks from my mouth; I haven’t been outside the shop for hours because of two bridal consultations and a busy delivery day. Bypassing the front door, I rest my eyes along Sunset, letting my blood cool.

With a bird as your Echo Park tour guide, you’d see Dodger Stadium looking east. Due west, Sunset Boulevard forks, leading toward Santa Monica and the beach in one direction, or on to Hollywood Boulevard in the other. The small notch on Sunset where La Rosa Blanca stands holds unique history within its two square miles. As I so pointedly reminded Emilio, my family was a part of that history. Same for the Avaloses and their bike shop.

Lately, though, Sunset Boulevard looks less cohesive than ever. There’s the odd indie store. A Starbucks across the street from an old special-occasion dress shop. Our beloved muraled walls host trash at their feet. Shiny, well-kept places gleam next to forgotten ruins.

Rusted iron bars cage in too many windows from a time, well after my bisabuelos and abuelos arrived from Cuba, when crime and rising rents forced so many out. A few have stayed. Pride that my family and our business have remained branches through my chest. If Echo Park still has one thing not rusted and boarded up, it’s legacy. Isn’t that worth more than big-business donuts?

“¡Clarita, ven!”

Abu’s voice carries through brick and glass. When I return to La Rosa Blanca, I find him in the showroom, where Vivaldi pours from the speakers and we serve bubbly drinks to clients. It makes it more bougie, no? Mamita remarked once. My abuelo rarely sits in this room. Now he perches on the edge of the settee as if he doesn’t completely trust the workings of the plush jade velvet. It’s mid-June, so his tan is in stage one.

“What’s up?” I ask, dropping into the space beside him.

He motions toward the picture windows flanking our front and side walls. “I should be asking you the same thing.”

My next breath sticks. Abu is a living floral message card. Pages of commentary and concern dropped into a single line. Apparently, he witnessed most of what went down between Emilio and me.

“Everything hit me at once,” I admit, making a detour around anything Avalos. “I got your cross frame, and the funeral became super real. And no design I’ve come up with seems good enough for el señor.”

“But you will figure it out. You have the talent and creativity. And remember, when the estate manager sent the order, Salvador specifically left a note that he wanted you to make his cross.” My abuelo pats my knee. “Use what you know and loved about him, and what you love about Echo Park, too. Because he sure loved this place.”

My eyes glaze with moisture. “So much, which is part of the problem. Just now, I went outside and saw that Ana moved out for good.”

“Claro.” Abu makes it more breath than word.

“After everything Señor Montes did for Echo Park, he couldn’t save Varadero.” He’d tried, though. Organizing fundraisers and contacting local media outlets. But it wasn’t enough. “Those boards and nails are all wrong.” Along with Hole Punch Donuts and Emilio’s questionable involvement in their Sunset takeover.

Abu hinges forward, resting chapped elbows on his thighs. His short-sleeved button-down shows off the forearm rose tattoo Mamita side-eyed for months when I was nine. “Between internet travel sites and her new lease terms, Ana couldn’t make it work anymore.”

A moment of fear grips my chest. “What about our place? Are we doing okay?”

“It’s not your job to worry—”

“It is my job.” I feel my cheeks flush with heat. “La Rosa Blanca will be mine one day, and now you’re saying that—”

“No, nena.” Abu cups my shoulder. “I am not saying that yet. We are okay for today.”

Relief comes, but only by half. “But you’re not sure about tomorrow.”

“We’re getting by,” he stresses. “All you need to worry about is enjoying your beautiful work here and your education.”

Something coloring Abu’s tone and worming through his body language makes me fear he’s leaving out key details. Either way, he’s wrong. We might be okay this second—but the future belongs to Papi and me, so I need to keep it safe. And what Abu doesn’t want to say, but what I know simply by being a part of this community, is that it’s not enough to rely on your past alone. To keep it alive, you have to be more creative than what’s new. A step ahead, an inch smarter.

But with me, there’s even more. Bigger than keeping on the lights and placing bouquets into hands. My past makes me long to do more than simply live—I want to thrive. My birth mother abandoned me and my dad ten days after I was born. All she left me was my name. I want it to mean something. It’s important for me to leave this world with something that lasts. Clary Delgado was here, and it mattered.

I just don’t know what that something looks like yet, which is annoying for someone who generally likes to know things.

On this summer day, staring out the window at Sunset Boulevard, I know one thing for sure. I promise La Rosa Blanca, and my family, and myself that our entrance will never be boarded up against our wishes. Delgados will decide when it’s time for our white rose to die.

One

Clary (Salvia sclarea): The clary or clary sage is a flowering plant native to the northern Mediterranean Basin, along with some areas in North Africa and Central Asia. The plant has a long history as a medicinal herb and is now grown all over the world for its essential oil.

When I tell people I work with dying things, I’m only joking. For a brief stretch of beautiful, though, picked flowers appear deceptively alive. Days for most, weeks for some. I get them during this small pocket. I trim ends and strip thorns, arranging them into the kind of art that only lasts in photos. Or if you have a family like mine—maybe a Cuban abuela like Mamita—you keep them mummified, their afterlives shriveled brown. Throw away your quinceañera bouquet or your homecoming boutonniere before your abuelita or mami enshrines it? Why would you ever want to invite the wrath of an elder Latina?

Day-old tulips are the worst. If not properly prepped, their bulbous heads bend lower and lower until they’re kissing tabletops and dropping bits of black pollen. This afternoon, the arrangement on my counter features no tulips. I call this one Sunset Echo, both for the area of central Los Angeles where we live and work, and for the colors: an upward spray of roses imitating a Malibu sky before dusk. As a base, I lined the rim of a canister with a circle of white hydrangeas and a layer of apple-green cymbidium orchids and Hypericum berries.

“Oye, paging Clary Delgado, thief of my favorite denim shirt!” Lourdes calls from the rear loading bay.

My friend appears as I place a coral rose in one of the most expensive arrangements available at La Rosa Blanca, my family’s florist shop. “For the millionth time, it wasn’t me.” I add one last sprig of berries.

“Wow, fancy.” Lourdes updates her delivery tablet. “Wait, that’s for Jody Ramirez on Russell? I was just there last week. Her dude’s totally cheating.”

“Lulú!” Her nickname darts off my tongue. I said what I said is written plainly across her face. “Yeah, well, this is his third order this month. The word sorry’s been on every card.”

“Mm-hmm,” she says. “And he picked Sunset E? Spendy. He’s busted.”

Also waiting for lucky recipients are four smaller arrangements. Lourdes carts those out while I pack the container for the short drive from Echo Park to Los Feliz.

When our junior year at Silver Lake Charter School ended three weeks ago, Lourdes joined our delivery team for some summer cash. Four days a week, she drives one of the La Rosa Blanca vans around Greater LA, transporting standing orders for hotels and restaurants and “I’m sorry for whatever reason this time” arrangements.

I tuck the customer’s message into the box. There’s something about these little flat cards I’ve always loved—that it doesn’t take an overblown word dump to make a big impact. Our most popular dedication is a simple Thinking of you. Perfect.

My friend returns, her lashes fluttering with the promise of a little neighborhood chisme. I keep floral dedications confidential, but this is Lourdes Colón, my trusted ally since fifth grade. “Okay, okay. Today it’s ‘Sorry, babe. Sunnier days ahead,’?” I quote from memory.

Lourdes snorts dramatically. At five-four, she stands two inches shorter than me, but her hair is another something. Waist-long and asphalt black, it acts like our personal life gauge. Feeling flushed, or is it only the weather? Consult Lulú’s hair, which swells in high humidity. In SoCal’s nonexistent fall season, her locks flat-iron themselves and track the Santa Ana wind as well as any scientific instrument. Sometimes, she’ll gather the whole mass forward and hide behind it like a curtain. Do not disturb. I respect the hair.

“Me voy,” Lourdes says, and grabs the box. “Oh, your abuelo just finished the frame for Señor Montes’s funeral cross.” Her face dims as she backs away. “It’s in the back when you’re ready.”

My next breath hitches. Señor Montes. It’s been two weeks since we learned our beloved eighty-nine-year-old community leader checked into the hospital (for what, we still don’t know) and never came home. Salvador Montes held me as a baby and watched over so many of us local kids. A fierce Echo Park advocate, he was never too far from his friends, a cafecito, and a Cuban domino set.

I find the huge cross-shaped wreath frame Abu made—ready for my floral design—and can’t help the fall into pure memory. At the forefront, there’s the jovial Señor Montes stopping by the shop on his afternoon walk after I arrived from school. Every time, I’d take a single scrap bloom and pin it to his lapel. Now, with his memorial two days away, I have to form a hundred flowers into something worthy enough for goodbye. And for the first time since I began working here as a kid, I don’t know how to start.

Hissing and crackling sounds from the two-way radio; I leave the cross and my design sketchbook for now.

“Rose Two here,” Lourdes announces over the airways. “We have a situation. I repeat, a situation. Over.”

Lulú finds too much amusement in the delivery van communication system. She’s the one who named the three La Rosa Blanca vehicles in order of size. Rose Two is our midsize cargo van. I grab the radio. “What situation?”

“You didn’t say ‘over.’?”

Way too much amusement. “Just tell me.” Ugh, Lourdes. “Over.”

“I’m stuck. There’s a big truck blocking the driveway and tons of bikes in the way. Over.”

The culprit’s no great mystery. Our historic storefront faces bustling Sunset Boulevard, but our corner property also has a fenced rear lot where we construct floral installations and park the vans. The gated driveway is directly across the street from the side wall of Avalos Bicycle Works. Their shop faces Sunset, too, but they don’t have any loading space.

“On it,” I announce.

Outside, I hang a right and march around the side street we share with the bike shop. Lourdes waves from the window of Rose Two. Sure enough, the truck is using our property to unload, but no one’s around. The driver locked a group of road bikes to our gate with one long tether right in front of the exit. Resourceful.

I wedge the radio into my jeans pocket and send a text to Emilio.

Me: I’m assuming that the truck and bikes outside have something to do with you guys?

Emilio: Racing team dropping them off for maintenance

Me: And blocking our driveway

Emilio: Is this the flower shop owner’s version of get off my lawn?

I glare at the phone, wishing that instead of a talking bubble, it was Emilio Avalos’s tanned, angular face. I need him to see my glare.

Since we were kids with neighboring everything, there’s been an ongoing bout of strategic play between us, like a living version of the domino game Señor Montes played daily. It varies, but just as in dominoes, winning between Emilio and me usually amounts to who can outsmart the other. Or out-annoy. After years of practice, we’ve gotten good at doling out comeback quips like those little ivory tiles with black dots. We know when to play them.

Get off my lawn? Cute. Like Abu has ever yelled that from our kitchen window.

Me: We can provide you with some excellent landscape maintenance references. Meanwhile, Lourdes has DELIVERIES

Emilio: My lawn is perfectly trimmed, thank you

Emilio: Yeah, yeah we’re coming

Moments later, Emilio strides out of Avalos Bicycle Works, followed by his dad and a couple workers from their repair department. The driver jogs up to the cab and proceeds to move forward, and the guys unlock the chained-up bikes.

Emilio’s expecting annoyance, so I unclench my jaw and try to appear extra calm. Underneath, there’s a brisk pull of adrenaline. “Feel free to move the truck back after Lourdes leaves,” I offer with great diplomacy.

“Cool. But why didn’t she just call me or Papi?” Emilio asks. “Lourdes needs you out here playing traffic guard, Thorn?”

He’s called me this for years, maintaining that a girl who spends half her day stripping roses of their one painful flaw, and the other half aggravating him, deserves such a moniker. If I’m being honest, I’ve never minded the Thorn nickname. But I’ll never let him know that.

Dropping my own nickname for Emilio now would seem too predictable. “You’d rather deal with a ragey Puerto Rican than me?”

Rage might be stretching things. One glance pegs Lulú as way too entertained watching my exchange with Emilio, chin perched on folded arms over her rolled-down window.

“It’s funny you think you’re the safer bet.” Emilio grins infuriatingly.

The horn beeps twice; with her path finally cleared, Lourdes rolls away with a cheerful wave.

“A-ny-way,” Emilio says. “The driver came in asking for help unloading, but he saw this new mountain bike, and Papi and I got carried away with the specs for a minute. Sweet ride.”

“If you say so.”

His eyes twitch with perplexity—the kind where he has to rewind what I’ve said to see whether or not he should be offended. Half a second later, he pivots toward Sunset Boulevard. “Wait, Varadero Travel closed?”

I nod, wincing at the darkened windows and boarded entrance. “As of today.” Another founding piece of Cuban Echo Park is gone, just like that.

Emilio crosses his arms loosely; they’re carrying twice as many grease stains as his gray T-shirt. “Hopefully she’ll find some cheaper digs off Sunset.”

“Why should she have to, though? Ana’s parents started that agency. Right there.”

“It’s sad, but what can we do? Times change. What if we’re supposed to let the neighborhood move the way it moves?”

Move? How fitting. But this issue is about more than Emilio’s habit of sitting near doorways and hovering under exit signs. “Our businesses started at the same time as Varadero. You’re okay with more Cubans losing a big part of who we are?” I press. “Do you think Señor Montes would’ve been down with that take after he devoted his life to Echo Park?”

Emilio lets out a thick exhale. “Listen, you know I loved that guy. And our history is a great thing.” He motions to the fence where the bikes were chained. “But our past isn’t made of links that lock for good. I don’t understand why we have to be so massively tethered to it.”

My mouth drops. “Tethered? Try grounded to everything we came from.” I motion across the street to the former travel agency. Its side wall mural with two macaws flanking a slice of Cuba’s Varadero Beach adds big Latino vibes to that corner. But now… “I can’t believe the building sold to Hole Punch Donuts.”

Emilio studies the pavement. Twists his jaw.

“What? What do you know?”

“That they make ridiculously good donuts.”

Nice try, Avalos. I cough, sharpening my stare.

“Okay, okay,” he says. “I knew Hole Punch was gonna open somewhere on Sunset. About a year ago, they posted for people to suggest new locations, and I said that Echo Park needed a shop. Then there were a couple DMs. The CEO saw that my family owns a business around here, and he reached out.”

“Oh my God, this is your doing?” I jab a finger, narrowly missing his chest.

“Seriously?” Emilio pantomimes devil horns on his head. “You think I got up one day jonesing for a donut and thought, ‘Hey, what sweet, respected Cuban and their business can I personally boot off Sunset today?’?”

I square my stance. “I didn’t say that. I said you had a part in the sale.”

“Not like you mean! I made a general suggestion. How could I possibly know they’d buy Ana’s whole building? All I wanted was a double cream glazed.”

“But you just said they—” Oh, he totally said, but my head is now a trash bin of confusion and runaround. “All I’m saying is you seem to care more about your sugar fix and something shiny going in than the cost. Or Ana. Or Echo Park history and…” I rattle my head back and forth.

“And we’re back to the start,” he says. “Surprise, surprise.”

“Hey, pequeño, phone call!” Dominic waves from the bike shop entrance. At six-one, there’s nothing pint-size about Emilio. But Dominic Trujillo’s rank as Emilio’s bestie and repair department whiz lets him get away with tons.

“So, that’s me,” Emilio says.

“Yup.”

But he doesn’t turn. We’re just standing here.

A few seconds pass before he powers back on with a twitch and struts away. The atmosphere feels lighter with him gone—even though this is hardly the first time I’ve argued with Emilio or challenged him about giving up on our shared heritage and our place here. Today, the threat is too close—only a few strides across Sunset. And coming right off Señor Montes’s death, it feels too personal.

Air leaks from my mouth; I haven’t been outside the shop for hours because of two bridal consultations and a busy delivery day. Bypassing the front door, I rest my eyes along Sunset, letting my blood cool.

With a bird as your Echo Park tour guide, you’d see Dodger Stadium looking east. Due west, Sunset Boulevard forks, leading toward Santa Monica and the beach in one direction, or on to Hollywood Boulevard in the other. The small notch on Sunset where La Rosa Blanca stands holds unique history within its two square miles. As I so pointedly reminded Emilio, my family was a part of that history. Same for the Avaloses and their bike shop.

Lately, though, Sunset Boulevard looks less cohesive than ever. There’s the odd indie store. A Starbucks across the street from an old special-occasion dress shop. Our beloved muraled walls host trash at their feet. Shiny, well-kept places gleam next to forgotten ruins.

Rusted iron bars cage in too many windows from a time, well after my bisabuelos and abuelos arrived from Cuba, when crime and rising rents forced so many out. A few have stayed. Pride that my family and our business have remained branches through my chest. If Echo Park still has one thing not rusted and boarded up, it’s legacy. Isn’t that worth more than big-business donuts?

“¡Clarita, ven!”

Abu’s voice carries through brick and glass. When I return to La Rosa Blanca, I find him in the showroom, where Vivaldi pours from the speakers and we serve bubbly drinks to clients. It makes it more bougie, no? Mamita remarked once. My abuelo rarely sits in this room. Now he perches on the edge of the settee as if he doesn’t completely trust the workings of the plush jade velvet. It’s mid-June, so his tan is in stage one.

“What’s up?” I ask, dropping into the space beside him.

He motions toward the picture windows flanking our front and side walls. “I should be asking you the same thing.”

My next breath sticks. Abu is a living floral message card. Pages of commentary and concern dropped into a single line. Apparently, he witnessed most of what went down between Emilio and me.

“Everything hit me at once,” I admit, making a detour around anything Avalos. “I got your cross frame, and the funeral became super real. And no design I’ve come up with seems good enough for el señor.”

“But you will figure it out. You have the talent and creativity. And remember, when the estate manager sent the order, Salvador specifically left a note that he wanted you to make his cross.” My abuelo pats my knee. “Use what you know and loved about him, and what you love about Echo Park, too. Because he sure loved this place.”

My eyes glaze with moisture. “So much, which is part of the problem. Just now, I went outside and saw that Ana moved out for good.”

“Claro.” Abu makes it more breath than word.

“After everything Señor Montes did for Echo Park, he couldn’t save Varadero.” He’d tried, though. Organizing fundraisers and contacting local media outlets. But it wasn’t enough. “Those boards and nails are all wrong.” Along with Hole Punch Donuts and Emilio’s questionable involvement in their Sunset takeover.

Abu hinges forward, resting chapped elbows on his thighs. His short-sleeved button-down shows off the forearm rose tattoo Mamita side-eyed for months when I was nine. “Between internet travel sites and her new lease terms, Ana couldn’t make it work anymore.”

A moment of fear grips my chest. “What about our place? Are we doing okay?”

“It’s not your job to worry—”

“It is my job.” I feel my cheeks flush with heat. “La Rosa Blanca will be mine one day, and now you’re saying that—”

“No, nena.” Abu cups my shoulder. “I am not saying that yet. We are okay for today.”

Relief comes, but only by half. “But you’re not sure about tomorrow.”

“We’re getting by,” he stresses. “All you need to worry about is enjoying your beautiful work here and your education.”

Something coloring Abu’s tone and worming through his body language makes me fear he’s leaving out key details. Either way, he’s wrong. We might be okay this second—but the future belongs to Papi and me, so I need to keep it safe. And what Abu doesn’t want to say, but what I know simply by being a part of this community, is that it’s not enough to rely on your past alone. To keep it alive, you have to be more creative than what’s new. A step ahead, an inch smarter.

But with me, there’s even more. Bigger than keeping on the lights and placing bouquets into hands. My past makes me long to do more than simply live—I want to thrive. My birth mother abandoned me and my dad ten days after I was born. All she left me was my name. I want it to mean something. It’s important for me to leave this world with something that lasts. Clary Delgado was here, and it mattered.

I just don’t know what that something looks like yet, which is annoying for someone who generally likes to know things.

On this summer day, staring out the window at Sunset Boulevard, I know one thing for sure. I promise La Rosa Blanca, and my family, and myself that our entrance will never be boarded up against our wishes. Delgados will decide when it’s time for our white rose to die.