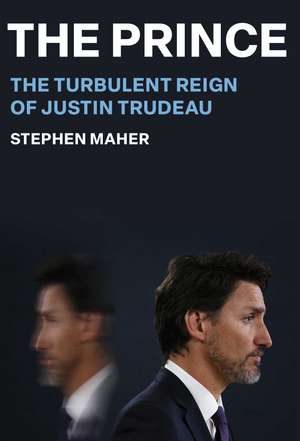

The Prince

Autor Stephen Maheren Limba Engleză Hardback – 28 mai 2024

The first comprehensive biography of Justin Trudeau as prime minister—an honest, compelling story of his government’s triumphs and failures, based on interviews with over 200 insiders and Trudeau himself.

As one of the longest-surviving prime ministers and son of the legendary Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Justin Trudeau is near royalty in Canada. But how did this former high school teacher with no noteworthy accomplishments put together a team that managed to take over the Liberal Party and bring it from third place to a majority government in 2015? The Prince shows just that. In this first comprehensive history of the Justin Trudeau government, veteran journalist Stephen Maher takes readers behind the scenes of a tumultuous decade of Canadian politics. Through hundreds of interviews with political insiders, he describes how Trudeau—a Canadian prince—had the famous name, the political instincts, the work ethic, and the confidence to overcome errors in judgment and build a global brand, winning in the boxing ring and on the debate stage. And then things changed as key people left the Trudeau team and the government lost direction.

Trudeau is an enigmatic figure—a politician who has been in the public eye since childhood and seeks attention but has always concealed his actual feelings from those around him. He has shown admirable strength and skill, deftly handling Donald Trump in trade deals and international meetings and in leading Canada through the COVID-19 pandemic. He has delivered substantial results for people within his political coalition—the most successful attack on poverty in a generation, real progress on climate change, and a sustained application of money and political capital to Indigenous reconciliation. Even as the government overcame major challenges, however, errors in judgment and personality conflicts wasted political capital. Trudeau has struggled to manage his own office, with devastating consequences, and alienated people outside his coalition, to the point where he can’t hold a public event without protesters screaming curses at him.

The Prince takes readers behind the curtain as the government goes from triumph to embarrassment and back again, revealing the people, the conflicts, and the struggles both in the government and on the opposition benches. Above all, it traces why this ambitious government led by a global media darling is now so unpopular it is in danger of imminent collapse.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 60.82 lei 23-35 zile | +34.42 lei 6-10 zile |

| Simon&Schuster – 9 oct 2025 | 60.82 lei 23-35 zile | +34.42 lei 6-10 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 107.61 lei 23-35 zile | +57.18 lei 6-10 zile |

| Simon&Schuster – 28 mai 2024 | 107.61 lei 23-35 zile | +57.18 lei 6-10 zile |

Preț: 107.61 lei

Preț vechi: 139.14 lei

-23%

Puncte Express: 161

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.02€ • 21.98$ • 16.48£

19.02€ • 21.98$ • 16.48£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 03-15 aprilie

Livrare express 17-21 martie pentru 67.17 lei

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781668024492

ISBN-10: 1668024497

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: 8-pg 4-C photo insert

Dimensiuni: 155 x 232 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.58 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

ISBN-10: 1668024497

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: 8-pg 4-C photo insert

Dimensiuni: 155 x 232 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.58 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Notă biografică

Stephen Maher has been writing about Canadian politics since 1989. As a columnist and investigative reporter for Postmedia News, iPolitics, and Maclean’s, he has often set the agenda on Parliament Hill, covering political corruption, electoral wrongdoing, misinformation, and human rights abuses. He has also won many awards, including the Nieman Fellowship at Harvard University, the Michener Award for meritorious public service journalism, the National Newspaper Award, two Canadian Association of Journalism Awards, a Canadian Hillman Prize, and has been nominated for several National Magazine Awards.

Recenzii

“Maher delivers a full-length treatment of the Prime Minister and his government that is both comprehensive and insightful. . . Stephen Maher has delivered a thoroughly researched and fair-minded accounting of Justin Trudeau’s accomplishments and failings. If journalism is the first draft of history, The Prince is a convincing second draft.”

— The Globe and Mail

“Sensational . . . It deftly captures what went on behind the scenes in Trudeau’s big successes, along with his big failures. The book’s strengths are in Maher’s interviews with top political players who speak candidly about what it’s really like in political Ottawa’s backrooms. The book is a must-read for anyone interested in politics and the prime minister.”

— The Hill Times

“An extraordinary book which traces this descent into hell is becoming a hit in English Canada. It's definitely worth reading if you want to understand how Trudeau got so low in the polls today.”

— Le Journal de Montreal

“I just finished Stephen Maher's The Prince and highly recommend it, even to those who closely follow Canadian politics. It’s the best Justin Trudeau biography I’ve read so far, and it is fair, accurate, and balanced.”

— DON MARTIN, columnist, CTVNews.ca

“[An] engaging and even-handed book on the prime minister”

— LAWRENCE MARTIN, Public Affairs Columnist, The Globe & Mail

“The Prince is a fast-paced, highly readable political narrative informed by interviews with more than 200 insiders, including Trudeau himself. . . The book carefully plots the downward trajectory of Trudeau’s time in power.”

— Zoomer.com

“This is a compelling examination of Justin’s time in office.”

— Hello! Canada

“Maher has juicy stuff from behind the scenes.”

— The Hill Times

“Compelling new book. . . as authoritative as it is newsworthy.”

— SaltWire.com

“The Prince is a valuable political recent history and overview.”

— Miramichi Reader

— The Globe and Mail

“Sensational . . . It deftly captures what went on behind the scenes in Trudeau’s big successes, along with his big failures. The book’s strengths are in Maher’s interviews with top political players who speak candidly about what it’s really like in political Ottawa’s backrooms. The book is a must-read for anyone interested in politics and the prime minister.”

— The Hill Times

“An extraordinary book which traces this descent into hell is becoming a hit in English Canada. It's definitely worth reading if you want to understand how Trudeau got so low in the polls today.”

— Le Journal de Montreal

“I just finished Stephen Maher's The Prince and highly recommend it, even to those who closely follow Canadian politics. It’s the best Justin Trudeau biography I’ve read so far, and it is fair, accurate, and balanced.”

— DON MARTIN, columnist, CTVNews.ca

“[An] engaging and even-handed book on the prime minister”

— LAWRENCE MARTIN, Public Affairs Columnist, The Globe & Mail

“The Prince is a fast-paced, highly readable political narrative informed by interviews with more than 200 insiders, including Trudeau himself. . . The book carefully plots the downward trajectory of Trudeau’s time in power.”

— Zoomer.com

“This is a compelling examination of Justin’s time in office.”

— Hello! Canada

“Maher has juicy stuff from behind the scenes.”

— The Hill Times

“Compelling new book. . . as authoritative as it is newsworthy.”

— SaltWire.com

“The Prince is a valuable political recent history and overview.”

— Miramichi Reader

Extras

Chapter 1: Fighter

I didn’t fully understand the Justin Trudeau phenomenon when I arrived in the Montreal riding of Papineau on October 2, 2012, to cover the launch of his campaign for the leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada for the National Post.

I knew Trudeau was a celebrity who attracted attention wherever he went, but I was skeptical about his political future. It was hard to take him entirely seriously in those days. He had great hair, a famous name, and a friendly, open way with people, but he had no particular accomplishments for the job. He made jokes that weren’t funny, and when he talked about policy he often seemed like a poser, with convictions based on his own inclinations rather than a deep understanding of the issues. He looked like a charismatic lightweight, one of those characters who show up on the Hill, strut and fret for a season or two, and then wander off to a less demanding career. Politics, Max Weber wrote, is the “slow boring of hard boards.” Trudeau didn’t look like a slow borer of hard boards, unlike the other men he would face in Parliament if he won the leadership.

Stephen Harper, the incumbent Conservative prime minister, was an economist who had engineered the merger of the Canadian Alliance and the Progressive Conservatives. Through patience, ruthlessness, and guile, he had won three elections in a row—two minorities, in 2006 and 2008, and finally a majority in 2011. By the autumn of 2012, his government was fading in the polls, but he was serious. So was his chief tormentor, New Democratic Party leader Thomas Mulcair, a lawyer and former Quebec Liberal Cabinet minister who had been elected leader after the death of the popular Jack Layton. The interim leader of the Liberals, lawyer Bob Rae, the former NDP premier of Ontario and a talented off-the-cuff speaker with a deep understanding of Canadian politics, was of similar stature.

Trudeau, in contrast, was a former high-school teacher. He had never served as a minister and had made little impression in his four years sitting on the backbench amid the third party in the House of Commons. But there was more to him than his weak resumé. He was famous. In a Parliament of drudges, full of former mayors, car dealers, and immigration lawyers, Trudeau stood out like a red rose on a grey suit lapel. He was young and handsome. He wore flip-flops and skateboarded to the Hill. When he entered a room, people said, “Hey! There’s Justin!”

I first met him in Darcy McGee’s, an Irish pub on the corner of Sparks and Elgin Streets, before he was elected to Parliament in 2008. I was then Ottawa bureau chief for the Halifax Chronicle Herald and often went to Darcy’s, a gathering place for political staffers, journalists, and lobbyists. Trudeau, who was known only as the flamboyant son of our former prime minister Pierre Trudeau, came in with his friend Gerry Butts, a hulking, bearded Cape Bretoner. I knew Trudeau was a quasi celebrity, and already there was speculation that he might one day run for office. A network of highly placed people associated with Trudeau père were rumoured to be waiting for the day when another Trudeau was ready to seek office.

I struck up a conversation with Justin and, at some point, mentioned his father in passing. “That’s weird,” I said. “I just realized I’m talking about your dad.”

He looked at me, squaring his shoulders. “Oh,” he said, “I never forget I’m a Trudeau.” He looked confident, poised, his eyes fixed. Huh, I thought. He’s like a prince.

Over the next couple of years, I had a few beers with him. He was friendly and chatty and, without making the slightest effort, was always the centre of attention. Almost everyone found it exciting to be around him. He has been famous since birth, the first child of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and the beautiful Margaret Sinclair. That was the X factor that made his candidacy remotely plausible, that made him a wild card entering the deck on that October day in 2012 when he took the stage in Papineau.

The speech he gave that night in Papineau did little to explain why he wanted to lead the party or why the party should lead the country. He praised Canada, the Liberal Party, progress, national unity, diversity, the environment, youth, and First Nations, and promised to work for the middle class. In the Globe and Mail, Daniel Leblanc described the speech as laying out an “ambitious but vague agenda.” The only substantial point was his personal relationship to Canadians. “Think about it for a moment: when was the last time you had a leader you actually trusted? And not just the nebulous ‘trust to govern competently’ but… the way you trust a friend to pick up your kids from school, or a neighbour to keep your extra front door key? That’s a respect that has to be earned, step by step.” Trudeau argued that Canadians knew him. “I feel so privileged to have had the relationship I’ve had, all my life, with this country, with its land, and with its people,” he said. “We’ve travelled many miles together, my friends. You have always been there for me.”

Later I spoke with Butts, expressing mild skepticism about Trudeau. He laughed and assured me Trudeau’s name recognition was likely “the highest for a leadership candidate in the history of the country.” What I didn’t know, but he did, was that Canadians wanted Trudeau to be prime minister. “The positive vibe that people have about him shows they’re not satisfied with what they have in leadership and they’re hoping for something more. In that sense, it has nothing to do with him and his personal attributes other than a kind of positive feeling they attribute to him. And our job, and his job, is to work our collective arses off to show people that he can be about something more.”

Butts had already been working his arse off on the project. “The Trudeau organization starts with one person, Gerald Butts,” says David Herle, a pollster and strategist Butts had recruited to the cause. Another insider called Butts the “mastermind” behind it all: “The thing that impressed me most about him was just his Rolodex. I’ve literally never seen anybody who was so good at accumulating friends and contacts, internationally, across the country, in this town, wherever. There’s just one guy. He’s got some kind of supernatural skill, finding powerful people and getting close with them.”

“Gerry is my best friend,” Trudeau told Leblanc in 2013. “He and I have been talking about the possibility and the potential of politics all my life.”

Butts is the son of a coal miner and a nurse from Glace Bay, a gritty working-class town near Sydney, Nova Scotia. When he was eight, the coal mine blew up, killing ten men and throwing everyone else out of work. The steel industry in nearby Sydney was slowly dying, and the moratorium on cod fishing was undercutting the fish-processing industry. There were too many people and not enough jobs. Politically, the area has always been left wing, influenced by the Antigonish Movement—a Catholic social justice movement that encouraged poor workers to organize co-operatives and credit unions. It was a place of strident unionism, patronage politics, hard drinking, Export A cigarettes, Celtic music, and working-class solidarity. Rather than following his classmates to St. Francis Xavier University, in nearby Antigonish, Butts, a promising student, went to McGill to study physics. He changed gears eventually and studied literature, doing his thesis on James Joyce’s Ulysses. In the debating club, he met Trudeau, who was then leery of introducing himself by his real name. He called himself Jason Tremblay and revealed his true identity only after he formed a favourable judgment of Butts. They bonded on the debating circuit, became fast friends.

After university, Butts cut his teeth working for Allan J. MacEachen, the Celtic Sphinx, a legendary Cape Breton political mastermind who helped engineer Pierre Trudeau’s 1980 election victory. He did research for MacEachen’s memoirs, which gave him insight into the history of the party. Angered by the Progressive Conservative government of Mike Harris in Ontario, Butts went to work for the provincial Liberals, eventually becoming principal secretary to Premier Dalton McGuinty, helping to engineer two election victories for him and developing a reputation for political acumen.

Butts and Trudeau had an unusually close relationship. “They didn’t work together,” says Herle. “They were together. They were friends, as thick as thieves, vacationed together, planned this project together.”

JUSTIN PIERRE JAMES TRUDEAU was born on Christmas Day in 1971, less than a year after his father, Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, married Margaret Sinclair, a “flower child” twenty-nine years his junior.I Although Justin grew up in the lap of luxury, with chauffeurs, servants, and global travel, his childhood was traumatic.

The Trudeaus lived at 24 Sussex Drive, the prime ministerial residence overlooking the Ottawa River. In 1973, Margaret gave birth to Alexandre “Sacha” Trudeau—another son born on Christmas Day—and in 1975 to Michel, who died tragically in an avalanche in British Columbia in 1998. The artistic and adventurous Margaret was then unaware she was suffering from bipolar disorder, a psychological condition that leads to manic episodes followed by paralyzing depression. She found life at the residence oppressive, and the marriage broke down in spectacular fashion in 1977.

On the night of her sixth wedding anniversary, Margaret showed up at the legendary Toronto rock club El Mocambo with Ron Wood and Mick Jagger, where the Rolling Stones were about to take the stage for a two-night stand. Her appearance caused a sensation. The Stones were then long-haired bad boys, famous for their dedication to sex, drugs, and rock and roll. “I wouldn’t want my wife associating with us,” drummer Charlie Watts joked at the time. Tabloids feasted on the scandal, linking Margaret romantically to both Wood and Jagger, and she followed them to New York when they left town. At home in Canada, her husband stoically declined to comment.

The marriage ended within months, and the boys continued to live with Pierre. Margaret became a regular at New York disco Studio 54, dating Hollywood actors and self-medicating with alcohol and drugs, as she later recounted in three memoirs. She and Trudeau had terrible rows, particularly over money. Once when he refused to give her enough, she confronted him at home. After she threw herself at him and tried to scratch out his eyes, he pinned her to the ground, where she screamed and struggled until their young sons broke up the fight.

This kind of thing was terrible for the boys. In his memoir, Common Ground, released in 2014, Trudeau writes that he felt “a diminished sense of self-worth” because of his parents’ split. He missed his mother terribly and would try to make special events of her visits. He prepared for one by cueing up a song his mother liked—“Open Arms” by Journey—on the tinny record player in his room. As she opened the front door, he cranked up the volume and shouted from the top of the stairs, “Listen, Mom, it’s our song!” But she couldn’t hear it, and his treat fell flat.

This sad anecdote is what sticks with the ghostwriter who put the story on paper, Toronto journalist Jonathan Kay. In the Walrus years later, Kay wrote that he was struck by Trudeau’s childhood suffering, the extremity of which was still palpable years later as he interviewed him for the book. Trudeau is defined by “a need to deal with maternal rejection,” which colours the views of those around him, who are aware of his traumatic childhood. “What good is the glitz of being a prime minister’s son when you’re living a childhood parched of mother’s milk?”

Along with the trauma of his difficult childhood, his intimates think his role as a big brother is also significant. He was a leader in the family, trying to look after his younger brothers—and several stepsiblings—amid a complicated family life.

“Justin, 6, is a prince—a very good little boy,” his mother said in an interview in 1977. “Sasha, born Christmas Day, 1973, is a bit of a revolutionary, very determined and strong-willed. Miche is a happy, well-adjusted child, who combined the best traits of both brothers.”

In an interview in early 2024, Trudeau told me that his role within the family led him, ultimately, to politics. “When I was busy being big brother, eldest of a composite family, it was much more around making sure everyone played well or everyone had fun. That was my focus, and it was very much in the moment.” He believes this focus helped him develop skills “around responsibility, conflict resolution, reading people, figuring out what they need as opposed to what they want.” And in turn, those skills took him into the classroom. “Being the eldest led me to becoming a teacher, and that was the path I was on. This, for me, feels like a detour from teaching or a continuation of teaching… I’ll always be a teacher. I just happen to be, like so many teachers, doing something different right now, but I’m still a teacher.”

After Pierre left office in 1984, he moved with his sons to Montreal, to the stunning art deco Cormier House on Mont Royal. He enrolled Justin in Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf, the elite Jesuit school he himself had attended—as have most men who later became prominent Quebec politicians. Justin quickly developed a network of friends, mostly anglos, but he was tested by other students. In his memoir, he writes about one incident when a boy confronted him with an upskirt photograph of his mother, taken at Studio 54 and printed by an American pornographic magazine. He kept his cool, refusing the bully any satisfaction. “I learned at Brébeuf not to give people the emotional response they are looking for when they attack me personally. Needless to say, that skill has served me well over the years.”

Justin fit in socially but did not excel academically. When he flunked a psychology class, his father showed him his own report cards from Brébeuf in the 1930s—“a straight line of As stretching from top to bottom.” The exchange convinced Justin that he should follow his own path. If he worked hard, he decided, it would be for something important to him, not just a grade on a report card. He doesn’t mention it in the book, but in a speech he once admitted to what he called a “slight learning disability”—dyscalculia, an inability to do mathematics in his head. Whatever the reason for his academic struggles, Justin did not do well. Everyone who has spent time with him remarks on his keen intelligence, although not everyone agrees that he has a focused, disciplined mind.

After Brébeuf, Justin graduated from McGill with a bachelor’s degree in literature and from the University of British Columbia with a degree in education. Then he went backpacking in Africa and Asia, worked as a snowboard instructor and a bouncer, and eventually became a high-school teacher at a private school in Vancouver. He must have been seeking a different career path, however, because he started and abandoned two advanced degrees in the early 2000s.

Until he entered politics, Justin Trudeau had not distinguished himself except in ways connected to his family’s celebrity. In 2000, when his father died, he delivered a nationally televised eulogy at the funeral, concluding in tears with the line “Je t’aime, Papa.” Canadians found the eulogy touching, although critics in the media called it overwrought and sentimental—a pattern that has continued with Trudeau—with pundits sniffing at his emotional tone even as many voters find it sincere and affecting. In 2003, he was invited to be chair of the board of Katimavik, a national youth program started by his father. He promoted avalanche safety as a way of honouring the memory of his brother, acted in the TV movie The Great War, did some radio commentary, and drew big crowds on the speaking circuit. All along, he seems to have known he might end up in politics. “When it happens it will be in my own time,” he informed Jonathon Gatehouse of Maclean’s in 2002.

Years later, he told David Herle that politics was like an open door, waiting for him. “He said, so matter of factly… ‘David, I’ve always known my whole life that this would be available to me if I want.’?”

The remark is typical of Trudeau. He is aware of his privilege and open to discussing himself frankly. His father always presented a carefully composed mask to the world, maintaining an artful mystique that served him well in politics, never giving the public access to his inner life. Justin is better-looking than his father was but does not have his reserve. He also wears a mask, but it is simpler, projecting affability, empathy. Those emotions may be real, but his persona is a construction, something he has worked hard to develop. Early in life, he was forced to become hardened to the public gaze and has developed skin like a crocodile. He doesn’t let haters get to him. He can guard his private feelings from the world, presenting a cheerful public face without revealing his inner life.

“I think Justin Trudeau is deeply unknowable,” says one person who knows him and has studied him for years. “I think from a very early age he kind of sensed that anybody who wanted to get close to him was wanting to use him because of his name, and therefore he wears a mask. I think his affability is a mask. I think that he is a deeply guarded person who opens himself up to nobody. And I think that’s why he likes to keep the same people around him.”

People who socialized with Trudeau in his youth remember him as a playboy, a moderate drinker, a celebrity who was popular with women and caused scenes whenever he entered night clubs on boulevard Saint-Laurent in Montreal or Queen Street West in Toronto. He seems to have changed after he fell in love with the glamorous society reporter and personal shopper Sophie Grégoire, a vivacious and gracious person with a spiritual side. Grégoire had been one of Michel’s childhood friends, with happy memories of pool parties at Trudeau’s Montreal home. She charmed Trudeau when they co-hosted the 2003 Mercedes-Benz Grand Prix ball in Montreal, but when she emailed later to say hello, he didn’t reply because he was in a “very socially active phase,” he later told Maclean’s Lianne George. At the end of that active summer, he ran into her on the street. He chased her down and asked her out. Their first date, at Khyber Pass, on Avenue Duluth, ended with an intensely emotional exchange of devotion. As Grégoire told Vogue later: “At the end of dinner he said, ‘I’m 31 years old, and I’ve been waiting for you for 31 years.’ And we both cried like babies.” “I call him my prince,” she told Maclean’s, “because he treats me like a princess.” They married in 2005. Several men who would later play an important role in his government served as groomsmen: Gerry Butts, Tom Pitfield, Marc Miller, and Seamus O’Regan.

In 2006, Tom Axworthy, who had been a key advisor to Trudeau’s father, asked him to serve on a party renewal committee, which led him to mix for the first time with Liberals across the country. At the leadership convention that year to replace Paul Martin, Trudeau showed up in the entourage of Gerard Kennedy, a young and dashing former Ontario education minister. Trudeau gave the speech nominating him and thoroughly enjoyed himself. Butts had “never heard him this jazzed at anything” before, and he got the feeling “this guy’s going to run for office.” At the convention, however, Kennedy eventually threw his support behind Stéphane Dion, the donnish professor Jean Chrétien had raised to prominence in the aftermath of the 1995 Quebec referendum. With Chrétien’s support, Dion pushed through the Clarity Act to establish rules for a sovereigntist referendum. Dion was a strong minister, but he had poor political instincts, as the party would learn before long.

Trudeau, raised at the heart of Canadian politics, knowledgeable about the country, desirous of public attention, with a hide as thick as a rhinoceros’s, and no other appealing career prospects, was ready to enter the fray. He started by calling Dion to ask if he could run in the coming by-election in Outremont, one of the most desirable seats in Montreal for a star candidate. Dion hesitated, knowing that Trudeau was unpopular with Quebec Liberals. Among francophone nationalists, Pierre Trudeau is remembered as a despised centralizer, the icy figure who thwarted the ambitions of René Lévesque. “The entire Quebec wing of the party was against him,” a senior Quebec Liberal told me later. “Nobody wanted the Trudeau name.”

Instead of giving the opportunity to former astronaut Marc Garneau, a high-profile Liberal who had run unsuccessfully in Montreal in 2006, Dion gave the nomination to his friend Jocelyn Coulon, a University of Montreal professor without political experience. NDP leader Jack Layton, seeing an opportunity, sweet-talked Tom Mulcair, who had recently left Liberal premier Jean Charest’s Cabinet in a snit, to stand. Mulcair agreed to become a New Democrat and won the by-election, giving the NDP its first real foothold in Quebec—and Dion an enormous black eye.

So, instead of being handed an easy seat, Trudeau had to fight to win Papineau, a densely populated and diverse working-class riding in the heart of the city. It was then held by Bloc Québécois MP Vivian Barbot, a well-regarded women’s activist. Born in Haiti, Barbot fled that country with her family to escape political violence. The first woman from a visible minority to serve as president of the Quebec Women’s Federation and a former vice-president of the Bloc Québécois, she was a formidable opponent, but the riding was winnable for the right Liberal. Barbot had managed to squeak past Liberal incumbent Pierre Pettigrew by only 990 votes in 2006 at the height of the Liberal sponsorship scandal.

Before Trudeau could run against her, he had to win the nomination, and two local figures—municipal councillor Mary Deros and Italian newspaper publisher Basilio Giordano—stood in his way. Veteran Liberal organizer Reine Hébert, who knew Trudeau père and had run Chrétien’s Quebec Liberal leadership campaign, offered to help Trudeau. With his future on the line, he threw himself into the work. Even Sophie joined in, selling Liberal memberships in a grocery store parking lot. Italians, Greeks, Haitians, and South Asians in the riding—who credit his father with opening immigration to their families—were receptive to his pitch, and he won on the first ballot on the night of April 29, 2007. That was the easy part. To beat Barbot and win the seat, he would have to do a lot more.

FOR THE ELECTION AHEAD, Trudeau was advised to ask for help from Louis-Alexandre Lanthier, a seasoned political professional with good judgment and experience working for Ken Dryden and other Liberal politicians. He invited Lanthier for lunch in Ottawa, but their initial conversation was difficult. Lanthier wasn’t sure he wanted the job. In previous encounters, he had found Trudeau standoffish and aloof. He told him candidly: “I met you twice before and I was not impressed.” They sorted out their differences and started talking about how they could run a campaign. “If you want somebody to be getting you interviews with La Presse and the Toronto Star and whatever, I’m not your guy. If you want somebody to make you go door to door, bring you to clean parks… I can do that.” Trudeau replied that he intended to work at ground level, and he wanted Lanthier to help him.

He could not have had a better assistant. Lanthier grew up in the party. His mother, Jacline, had worked for Pierre Laporte, the Liberal deputy premier of Quebec, who was kidnapped and murdered by the Front de libération du Québec in 1970 during what came to be known as the October Crisis. Then just twenty-two, she had been with his family while they waited for news and learned of his murder. Raised in a household where the struggle with sovereigntists was an existential matter, Lanthier was a seasoned professional, with experience, patience, and judgment. He first campaigned for a Liberal candidate at the age of seven, delivering pamphlets on his bike.

Lanthier soon found he had a raw but hard-working candidate on his hands. Trudeau was willing to do the tough street-level tasks that candidates often try to avoid—participating in park cleanups, knocking on doors, handing out literature in malls and the metro. Lanthier trained Trudeau in the ways of politicking, teaching the tricks that veteran politicians learn along the way—how to greet people on the street and engage with them on their doorsteps.

Papineau is a dense, urban riding divided, like the rest of the city, by boulevard Saint-Laurent. On the west side is Parc Extension, an immigrant neighbourhood once dominated by Italians and Greeks and now, increasingly, by immigrants from the Middle East, South Asia, and the Caribbean—a quartier of shawarma shops, curry houses, mosques, and temples. It is a natural constituency for the Liberals, whom many immigrant voters favour. On the east side is Villeray, an old working-class francophone neighbourhood, where the Bloc Québécois is strong.

“People, at the first few times we went door knocking, they would yell at us,” Lanthier recalls. “They would slam the door. They would say he was the son of the devil.” Trudeau engaged cheerfully with them all, pointing to areas where they agreed. Lanthier has a picture of him sitting in the living room of one home and drinking beer with a group of young francophone sovereigntists who began as personally hostile.

Trudeau took Lanthier’s lead on how to sell himself to voters but not on policy. During a visit to one important mosque in the riding, for instance, Lanthier cautioned him to avoid discussing same-sex marriage. “I said, ‘Maybe we don’t raise this issue today when we meet with this group.’ And the first thing he does is he talks about gay marriage and the liberty of women.” When Lanthier chided him later, Trudeau replied: “No. You said it, but I thought it was important that they knew where I came from.”

TRUDEAU WON THE RIDING in the election of October 2008, besting Barbot by just 1,189 votes. It was an impressive victory because, under Dion’s leadership, the Liberals had lost eighteen seats. Dion had proposed a complicated environmental proposal—the Green Shift—that would have imposed a carbon tax to reduce emissions and distributed the money through progressive tax rebates. It was a thoughtful policy, but voters found it confusing. The Conservatives portrayed it as a zany Liberal cash grab promoted by a wacky professor. Before the election, an abortive coalition attempt—featuring Dion, Layton, and Bloc Québécois leader Gilles Duceppe—helped Stephen Harper portray his opponents as reckless. Dion, whose English was shaky, never connected on the campaign trail.

Trudeau got himself an apartment in Ottawa and set about learning the ropes, bringing his natural exuberance to the staid parliamentary precinct. There was a significant amount of eye-rolling in his early days on the Hill. It started during his Papineau campaign when he posted a treacly, overly earnest video on his campaign website in which he alternated rapidly from French to English, overacted, and seemed extremely pleased with himself. “You have no doubt noticed que ce video est un mélange of English and français. Although everything written on this site est disponible en anglais and in French, my personal videos seront bilingues.” A Quebec comedy troupe quickly produced a spoof video of a deranged-looking Trudeau switching back and forth between languages. That spelled the end of Trudeau’s mixed-language videos.

Pierre Trudeau had insisted that his children grow up at ease in both languages. The effortlessly bilingual Justin had a hard time accepting that not everyone is so lucky. In 2007, during a speech to elementary school teachers in Saint John, New Brunswick, he said it might be better to do away with French-language schools in the province. “The segregation of French and English in schools is something to be looked at seriously,” he suggested. “It is dividing people and affixing labels to people.” His comments reflected a surprising naïveté about New Brunswick language politics. The province’s Acadians, long treated as second-class citizens, had pushed hard to establish French-language schools and saw a separate system as the only way to prevent assimilation. They were willing to go into the streets when necessary to protect their language. In 1997, RCMP used tear gas and police dogs to attack Acadian parents protesting school closures. As an anglophone from neighbouring Nova Scotia, I found Trudeau’s gaffe astonishing. If I was aware of the long and difficult Acadian struggle for linguistic equality in New Brunswick, how could he not be?

The Société des Acadiens et Acadiennes du Nouveau-Brunswick issued a statement asking him to “mind his own business.” Trudeau apologized, and Dion asked voters to be indulgent. “He is new. He will likely have to explain his thoughts further.”

Trudeau’s exuberance and confidence, his princely certainty in the importance of his ideas, have often led him to make comments he has later had to disavow. It is part and parcel of the certainty that led him to speak forcefully about his support for gay marriage in a mosque—an admirable belief in presenting his views forthrightly and bravely. The problem is that he had a similar certainty about matters where he didn’t know what he was talking about. It reflected the immaturity of an academic dilettante, someone whose opinions were always greeted with interest because of his charisma and family name but who lacked the intellectual discipline for which his father was famous.

Once in Ottawa, Trudeau proved to be a loner rather than a team player. Liberal MPs found him a bit much, as he continued to arrive on the Hill riding a skateboard. They resented the way reporters sought him out, ignoring his more experienced, harder-working colleagues, and found him uninterested in policy work. “When he showed up, I mean he used to sit in the corner of the caucus room, when Bob Rae was leading caucus, on his iPad—iPads were brand new then—and then he’d get up an hour early and leave,” one MP told me. His caucus colleagues may have been irked by his gaffes and flamboyance, but they were also keen to have him headline fundraisers in their ridings, where he was guaranteed to pack a hall. Some MPs complained, though, that he insisted on taking a cut, having them pay his riding association for the honour of his presence, which was not the way other MPs operated. He was eventually called on the carpet by the party and told he could not bill them so much for his appearances.

Trudeau’s legislative track record was unimpressive. He sat in the back-bench and served as his party’s associate critic for human resources and skills development (youth). In his first session, miraculously, he won the lottery that MPs hold to determine who gets to table a private member’s bill. Instead of finding an issue around which he could build support across party lines—the only way to advance a private member’s bill—he wasted the opportunity by presenting a bill to promote youth volunteer service, which the other parties swiftly killed.

None of it mattered, though, because Canadians remained fixated on him. He was interesting. There were admiring profiles in magazines, invitations to high-profile events. Strangers regularly stopped him on the street to wish him well. He split his time between Ottawa and Montreal, where he spent weekends with Sophie and Xavier, their son, who was born four days after the election. There was already speculation he might take over from Dion, but he shrugged it off.

Others were thinking about it though. In 2009, during a fact-finding trip to Israel sponsored by the Canada-Israel Committee, Trudeau got to know Bruce Young, a Vancouver Liberal who had been involved in politics since he volunteered for John Turner in 1984. Young had met Trudeau in 2006 when they were both involved with Gerard Kennedy’s campaign, but they really bonded as they toured around Israel.

After dinner one night, they ended up drinking scotch with kibbutzniks until the small hours in a Jerusalem pub. Young woke up the next morning in his hotel room with a dry mouth, a terrible headache, and a ringing phone. Trudeau was calling from the lobby. “Hey dude, we leave in five minutes and everyone’s here and you’re not.” Young splashed water on his face and rushed downstairs to join the tour. The first stop was a meeting with an Israeli foreign affairs official, who briefed the Canadians on the assassination of a Hamas leader in Syria the night before. Trudeau quizzed the official at length, showing a detailed knowledge of Iranian, Israeli, and Syrian politics. “Meanwhile, all I’m trying to do is, you know, keep down the five aspirin I’ve had for breakfast,” Young recalls. He was so impressed by Trudeau’s stamina that he called his wife later and told her: “He’s going to be the prime minister of Canada, and I’m going to help him.”

ON THE NIGHT OF May 2, 2011, Trudeau again won his riding of Papineau, this time by a margin of 4,327 votes. Barbot ran against him, but this time she came in third, behind a New Democrat. The NDP won fifty-nine of Quebec’s seventy-five seats in a historic shift that nobody saw coming until it happened. The party, never previously a force in Quebec politics, took off under the leadership of Jack Layton, who grew up in the Montreal suburb of Hudson but represented a Toronto riding. Beginning at a policy convention in Quebec in 2006, Layton had succeeded in changing NDP policies to appeal to left-wing nationalists who typically voted for the Bloc. A key piece of the puzzle was the Sherbrooke Declaration, which sought to nullify Dion’s Clarity Act, asserting that an NDP government would recognize a sovereignty referendum if the sovereigntists won 50 percent of the vote. For “soft nationalists,” it was a crucial policy, recognizing Quebec’s right to self-determination.

Many Quebecers wanted to get rid of Stephen Harper, who by that point had been governing the country for five years. They knew the Bloc could not replace the Conservatives and had not warmed to Liberal leader Michael Ignatieff. When Layton went on the popular Quebec Sunday night talk show Tout le monde en parle, he charmed the host, Guy Lepage, who called him a “bon jack,” a good guy. Quebecers agreed, and they elected dozens of previously unknown candidates, nicknamed poteaux orange—traffic cones—because they were orange and stationary. The most celebrated was Ruth Ellen Brosseau, an Ottawa barmaid who was elected in rural Berthier–Maskinongé even after it was revealed she took a mid-election vacation to Las Vegas.

In the rest of the country, the NDP did better, but not well enough to stop Harper from winning a majority. Ontarians, with painful memories of Bob Rae’s NDP government, did not follow Quebec’s lead, and at the last minute a small but decisive group of voters switched from the Liberals to the Tories to prevent an NDP government, delivering vote splits in close ridings that devastated the Liberals. Harper had focused on a powerful economic message while his party pummelled Ignatieff with attack ads. A Harvard professor with a celebrated career as a global intellectual, Ignatieff, who entered politics at sixty, never learned the political discipline necessary in modern politics and often seemed to be lecturing voters rather than listening to them. The Conservatives framed him effectively in a wave of TV ads that declared, “He didn’t come back for you.”

Layton helped deliver the coup de grâce in a debate when he attacked Ignatieff for missing votes in the House. An indignant Ignatieff sputtered that he wouldn’t take lessons from Layton. “Most Canadians, if they don’t show up for work, they don’t get a promotion,” Layton replied, delivering the most effective knockout blow in a Canadian election debate since Mulroney mauled Turner in the 1984 election over patronage appointments to Pierre Trudeau loyalists. When the dust settled, Ignatieff and Bloc leader Gilles Duceppe were gone, the NDP was in opposition, and the Liberals were in third place with just thirty-four seats—a record low.

It was a wrenching loss. The party that thought of itself as the natural governing party had overnight lost its dominant position. The Liberal Party of Canada was one of the most successful political parties in the world, governing Canada for seventy years in the twentieth century. Now it had been brought low, a victim, largely, of infighting. The internal battles between Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin were so toxic, so personal and virulent that many senior figures were pleased to see their opponents, rather than internal rivals, succeed. Liberals were out of touch and complacent, with aging MPs in (supposedly) safe ridings focused on their own careers, not the hard work of knocking on doors, raising money, and attending events.

At the time, it looked like a structural change—a permanent realignment along more ideological lines. The Liberal Party was a brokerage party, dispensing patronage and influence, managing regional, linguistic, and religious electoral blocs, moving forward with progressive policies when possible, insofar as it didn’t disrupt the delicate business of managing a fractious, regionally disparate country. The party more closely resembled Japan’s LDP, India’s Congress, or Mexico’s PRI than Labour in the United Kingdom or the Democrats in the United States, governing by straddling the middle, veering back and forth, assembling coalitions across ideological lines. As politics globally became more polarized in the twenty-first century, the big brokerage parties everywhere were losing their grip. Why should Canada be any different? It was the long-held ambition of some less progressive Conservatives—including Ernest (Preston’s father) Manning and Harper—to reorder the system so that the Conservatives and the NDP would take turns in governing. They wanted to break the cycle where they were too often on the outside looking in while a massive, unmovable Liberal blob ran the country, rewarding their friends in the Laurentian Elite and appointing one another to the Order of Canada. After the electoral wipeout of 2011, it looked as though they might finally get their wish.

We will never know what would have happened if Layton had not succumbed to cancer in August 2011, four months after he led his party to the opposition benches. He was an unusually good politician, a hard-working glad-hander with the common touch, a disciplined communicator who refused to be knocked off his talking points, and a patient and calculating strategist. If he had survived and faced Harper in the House, opposition to the Conservatives might have coalesced around him, giving the NDP the opportunity to behave like a government in waiting. And Trudeau might have found a different line of work.

In the aftermath of the Harper majority, Trudeau had been thinking about giving up politics, maybe leaving the country. “He thought he was going to leave politics in the summer of 2011, and he went out to Ucluelet and had a surfing holiday,” recalls Butts. “And Jack Layton died when he was out there.” That changed everything.

Trudeau says he was struggling with his role after Harper’s victory. “There was a moment in there where I was wondering if the drive to have an impact and change things and make a difference was not mistimed.” And yet, he was under pressure to run for the leadership. “Everyone said, ‘Okay, we tried two smart intellectuals in Stéphane [Dion] and Michael [Ignatieff], let’s go with the kid with the big name who we don’t know how smart he is. Maybe that’s the Hail Mary we need.’?”

Trudeau was afraid of being seen that way because he “knew how much work there was to do.” It wasn’t that with Layton gone the path was clear for a Liberal victory. “I really thought about family and the country and what I could contribute to it. A good man like that giving his everything to his last days in service to country—it just inspired me.”

WHEN HARPER WON A majority in 2011, he took a more combative tone than in his minority years. Progressives were shocked and dismayed to find supposedly liberal Canada led by an Albertan intent on shrinking government and creating the kind of country where pipelines could get built without much red tape. Dismayed and freaked out by Harper, lefty Canadians were casting about for champions. Trudeau answered the call.

In December, Conservative environment minister Peter Kent, a normally gentlemanly and thoughtful former CTV reporter, took a low blow at NDP MP Megan Leslie while she was questioning him about the government’s decision to withdraw from the Kyoto climate accord in a meeting in Durban, South Africa. The Conservatives had gone to Durban determined to undercut the climate deal and had declined to provide accreditation to opposition critics, like Leslie, presumably to prevent them from providing negative commentary to the journalists covering the event. Under pressure from Leslie, instead of defending his government’s position, Kent attacked her for not going to Durban.

“Mr. Speaker, if my honourable colleague had been in Durban, she would have seen that Canada was among the leaders in the…”

Before he could finish, he was shouted down by enraged opposition MPs, including Trudeau, who was then sporting long hair, a moustache, and a d’Artagnan soul patch. His words were rendered decorously in Hansard as “Some hon. members: Oh, oh!” But he didn’t say “Oh, oh.” He yelled at Kent, “Oh, you piece of shit,” which led to mayhem in the House. Kent insisted on an apology, which Trudeau delivered. Much ink was spilled.

Early in the new year, he was again making headlines. In a French-language Radio-Canada interview, he mused that if Harper kept running the country, “maybe I would consider wanting to make Quebec a separate country,” an awkward way of trying to undercut the sovereigntist argument. When he took heat on February 14, he went to the lobby of the House to respond, against the advice of party communications staffers Kevin Bosch and Daniel Lauzon, who thought it might go badly.

“The question is not why does Justin Trudeau suddenly not love his country, because the question is ridiculous,” Trudeau said emphatically, as if his patriotism should be beyond question. “I feel this country in my bones with every breath I take, and I’m not going to stand here and defend that I actually do love Canada, because we know I love Canada. The question is, What’s happening to our country?”

Trudeau’s performance was so over the top that the reporters standing around him were fighting not to giggle. He knew it had gone badly. “That didn’t go very well, did it?” he said to Bosch and Lauzon when he returned to the lobby. “You used to be a drama teacher,” Bosch said. “Not a very good one,” Trudeau replied.

Politicians don’t typically speak of themselves in the third person, and they don’t declare that they feel the country in their bones with every breath they take. But this kind of thing may not bother voters as much as it does jaded reporters. And perhaps Trudeau does feel Canada in his bones, or believes he does. When Jonathan Kay spent time with him researching Common Ground, he was struck by Trudeau’s knowledge of the country, which he has been travelling since he was a child.

Kay watched Trudeau do a speaking event at Algonquin College in Ottawa. “He was talking to a bunch of like, seventeen- and eighteen-year-olds, people barely out of high school. And somebody said, ‘Hey, what’s your favourite Canadian band?’ And honestly, if you’re like me, I’d say, um, Loverboy, Arcade Fire. And then the list runs out, right? He listed like ten bands in French, ten bands in English, named some of his favourite songs. And the whole room was just eating out of his hands. But I talked to him after, and he knew these bands. It wasn’t just like someone gave him a cue card, like names of Canadian bands.”

During this period, Trudeau decided he did want to lead the Liberal Party, beat Harper, and become prime minister. “He said, ‘I think I really want to do this,’?” Butts recalls. “?‘And I think if I don’t do it now, it’s never going to happen.’?”

A MONTH BEFORE TRUDEAU’S theatrical interview, Prime Minister Stephen Harper appointed thirty-four-year-old Patrick Brazeau to the Senate, the youngest senator in the chamber. An Algonquin from the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation, up the Gatineau River from Ottawa, Brazeau was national chief of the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, a group representing Indigenous people who lived off-reserve and tended to be more open to Harper’s pitches than those influenced by the Assembly of First Nations chiefs. Brazeau’s appointment angered many Indigenous people because they saw him as a suck-up to a government hostile to their interests. He also had a reputation as a hothead, with a record of behaving in a non-senatorial manner.

In 2012, Trudeau, with his eye on the leadership of his party, decided to fight in a charity boxing match. He had been training for years in a Montreal gym, and he and his trainer thought he was good enough. He first challenged Conservative MPs Peter MacKay and Rob Anders, but they wisely declined. Brazeau, who had a black belt in karate, jumped at the chance. Trudeau was delighted. He later told Rolling Stone: “I wanted someone who would be a good foil, and we stumbled upon the scrappy tough-guy senator from an Indigenous community. He fit the bill and it was a very nice counterpoint. I saw it as the right kind of narrative, the right story to tell.”II

Before the fight, Trudeau and Butts decided that Katie Telford, who had worked with Trudeau on the Kennedy campaign, was the organizer they needed to build a team. Telford grew up in Toronto, the daughter of public servants. As a young woman, she went to work for Gerard Kennedy when he was minister of education in Ontario and ended up, at twenty-five, as his chief of staff. She impressed many Liberals when she ran his vigorous though ultimately unsuccessful campaign for the Liberal leadership before moving to Ottawa to work for Dion.

She didn’t think the fight was a good idea. When she went out to dinner with Butts and Trudeau to talk about playing a role on his campaign, she tried to talk him out of it. She imagined him getting bloodied, which would look bad. “You let me worry about that,” Trudeau said. “You guys start thinking about the leadership.”

Ahead of the fight, the smart money was on the heavily muscled Brazeau, who looks like a tougher guy than Trudeau. Trudeau, who had been boxing regularly for twenty-five years, says he knew he could beat him, showing the profound confidence that is part of his character. “He’s got a black belt in karate, but we’re not doing a karate fight,” Trudeau told me. He was so sure he would win that he let his stepfather wager on him. “I ran into him at one point, [and he said], ‘You sure about this?’ ‘Yeah. I got this.’ He’s like, ‘Okay.’ And he turned around and made a handful of bets with his buddies at some great odds and made a lot of money off them because he knew that when I think I’ve got something, it’s because I’ve thought it through.”

Brazeau came out strong in the first round and hit Trudeau harder than he’d ever been hit before. But Trudeau was able to wait until Brazeau was out of wind and, by the third round, he was mauling him at will. He bloodied the senator’s nose.

The match was broadcast live on Sun TV, a short-lived right-wing network, with ringside commentary from Ezra Levant, who kept calling Trudeau “Shiny Pony.” Levant was forced to keep up his comments as Trudeau slowly beat the stuffing out of Brazeau. Tories, expecting that Trudeau would take a shellacking, were there in large numbers and quickly vacated after he triumphed.

The match was crucial to reframing Trudeau’s image, says Nik Nanos, CTV’s pollster of record. “The boxing match refuted every single claim that the Conservatives made. It refuted the fact that he was weak. It refuted the fact that he was not tough. One of the traps that the Conservatives fell into is that they created expectations for Trudeau that were so low that he realistically just stepped over that.”

The ink-stained wretches of the press gallery had a primal spectacle to write about and, tired of being kicked around by the Harper government, leapt at the chance to celebrate the new progressive champion. “Should Justin Trudeau stop playing coy, put family life on hold and leap into the Liberal leadership race, thereby saving the party of Laurier and Pearson, and perhaps the country, from certain doom?” wrote Michael Den Tandt in the Postmedia papers. “Since the big fight at the end of March—let’s face it, that was the turning point—disparaging references to Trudeau as ‘the Dauphin’ have been rare indeed.”

Teresa-Elise Maiolino, a Toronto sociologist, wrote in a 2017 paper that “media coverage of the boxing match provided Trudeau with the opportunity to transition from precariously masculine to sufficiently masculine.”

AFTER HIS PUGILISTIC TRIUMPH, Trudeau started to build a leadership team. Telford brought on Michael McNair. He had done the heavy policy lifting on Dion’s ill-fated Green Shift and stayed on to work for the even less successful Ignatieff. McNair, a wonk with master’s degrees from Columbia University and the London School of Economics, had left for a job on Bay Street. He agreed to come back as policy advisor, and, in the early days, was a jack of all trades, carrying Trudeau’s bags when necessary.

The first step, the team decided, was to gather a group of supporters to kick around ideas. They invited about thirty people, a mix of Trudeau’s friends and hard-nosed political operatives, for a weekend of discussion sessions at Mont-Tremblant, the most beautiful resort in Quebec—a village built in the style of Old Quebec at the base of a world-class ski hill. Tom Pitfield, whose father had been clerk of the Privy Council under Pierre Trudeau, handled the logistics, renting a chalet.

Pitfield, who is six years younger than Trudeau, was close to Michel Trudeau as a child. When his mother, Nancy, and Justin’s father died in the same year, the two young men were drawn together in their grief. They have remained close ever since, with Pitfield offering advice from outside the Ottawa bubble about politics and personal matters. His wife, Anna Gainey, was a former Liberal political staffer, and would eventually become party president. But back then, Pitfield, who has a master’s degree in political philosophy from the London School of Economics, was handling logistics. He was interested in policy, but Trudeau suggested he focus instead on digital strategy for the leadership campaign, and Butts convinced him to do it. At the time of the Tremblant meeting, he was already building the digital operation that would be at the heart of the Trudeau political machine for the next decade.

As the weekend started, Butts drove Telford to the Trudeaus’ chalet in the hills nearby to meet and have lunch with Margaret. Alexandre, known widely as Sacha, was there too—and he joined them as part of the team when the sessions began.

The participants gathered in a chalet, where Trudeau, Telford, and Butts led most of the discussions. Lanthier, now Trudeau’s executive assistant, was there, part of a significant Quebec contingent, as was Bruce Young from British Columbia, and former Mississauga MPs Navdeep Bains and Omar Alghabra, who would later serve as ministers. Many, including western organizer Richard Maksymetz, were veterans of the Kennedy campaign.

As they sat around a fire pit, participants discussed the way forward. Should they start a new party? Should the Liberals merge with the NDP? The idea was then being promoted by Chrétien and former NDP leader Ed Broadbent, who reasoned that vote-splitting on the left was allowing the Conservatives to divide and conquer progressive voters. The Quebecers were interested because the fundamental cleavage in that province was typically around the national question, whether Quebec should secede or not, so it seemed counterproductive for the federalist vote to be divided between two parties. But Liberals from English Canada were vehemently opposed. Maksymetz, Butts, and Telford were certain that whatever votes they might win on the left they would lose on the right. Advocates for a merger were convinced to give up the idea.

Butts had convinced David Herle to sign up, despite his misgivings about Trudeau, whom Herle thought of as a lightweight. Herle agreed to help, but he was occupied with the Kathleen Wynne government in Ontario at the time and suggested that Butts hire Frank Graves, president of EKOS Research Associates, to do the polling. Though non-partisan, Graves felt, with some evidence, that he had been persecuted by Harper’s people and wanted to see a change in Ottawa. He gave a presentation to the group at Mont-Tremblant, first running through slides that showed the country might be ready to switch governments. He found a mood of discontent in the land, the feeling that the country was going the wrong way. Three-quarters of the population, for example, said that the Canadian dream was getting out of reach. The numbers were not great for the Liberals either. The Conservatives and NDP were tied for first place with a percentage in the mid-30s, with the Liberals a distant third, below 20 percent. But there was reason to think the Liberals had room to grow: 45 percent of Canadians considered themselves “small-l liberals.” And Trudeau’s numbers were good: 38 percent of Canadians had a favourable view of him, compared with just 27 percent who were unfavourable. Thomas Mulcair’s numbers were better—42 percent to 26—but he was Opposition leader. Harper’s numbers were bleak: only 32 percent approved of him, and 56 percent disapproved.

As to the leadership race, which had yet to be called, Trudeau could expect to enter with a commanding lead, with the support of 26 percent. Former astronaut Marc Garneau, former finance minister Ralph Goodale, Quebec MP Denis Coderre, Nova Scotia MP Scott Brison, New Brunswick MP Dominic LeBlanc, and former MP Martha Hall Findlay were all basically tied for a distant second. Trudeau scored badly with Conservative supporters but performed well with Liberals, New Democrats, and Greens. Compared with Harper, he was seen as weak on the economy but had a strong advantage on social issues and the environment.

Graves told the group that Trudeau would probably have an “insurmountable lead” in the race. He was “a strongly recognized national figure who is seen in much more favourable terms than [Harper], or any of the plausible contenders for Liberal Party leadership.” But beating Harper in a general election would be a “much more elusive and uncertain goal.” Although Trudeau was viewed as having charisma, empathy, and love of country, Harper was seen as tougher. Mulcair, who was strong in Quebec, was regarded as the “most plausible option to depose the Harper government.” Yet Mulcair was anything but a sure thing: while the top-line numbers showed NDP strength, centre-left voters were persuadable: “There is a lot of churning and shifting and low levels of emotional engagement,” said Graves, who advised Trudeau to be “positive and future-oriented, decisive about real dominant progressive values,” and to emphasize “jobs and growth, economic progress and fairness.”

McNair, who had been researching the messages that were succeeding for Democrats in the United States, gave a presentation on the “economic context of Trudeau as a politician.” “It was at Tremblant where we settled on our economic stories that we’re here to help strengthen and grow the middle class,” he says. In retrospect, that message seems obvious, but at the time it was anything but. “That’s language that Liberals had often been uncomfortable with because just the language of class is not something that people were used to, even though most Canadians do self-identify as middle class.”

Butts left Tremblant convinced that the Liberals needed to be liberal again. From his perch in Queen’s Park, home to Ontario’s Legislative Assembly, he had observed a federal party that seemed to have lost its way, offering timid, neo-conservative economic policies. And after Dion’s defeat in 2008, the party concluded it was a mistake to offer ambitious environmental policies. “The takeaway from the weekend was that the problem with the Liberal Party was that it wasn’t very liberal, and it had obvious screaming telltale signs to voters who were liberal that it wasn’t liberal,” he says. From this conviction would follow—eventually—decisively progressive policies, on abortion, same-sex marriage, marijuana legalization, and the economy, but all of that would wait. Trudeau, the clear frontrunner of a race that hadn’t yet started, had no reason to roll out policies that his opponents could use to pin him down.

Before the coalescing Trudeau team could get to work, though, they had to sort out the Sacha factor. Trudeau’s younger brother was a key part of Team Justin at the time of the Mont-Tremblant meeting. People who attended expected him to keep on being part of the team, but it was not to be. While Justin resembles his mother, in his openness and creativity, Sacha is more like his father, more private. He is as guarded as Justin is open. “I was very close to my father and remain very close,” Sacha told Shannon Proudfoot in Maclean’s in 2016. “I live in his home, I’m the guardian of his private spirit.” He is a documentarian and has travelled to war zones around the world, including Liberia, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Darfur. When Liberals gathered at Mont-Tremblant, some thought he would be Bobby Kennedy to Justin’s JFK, seek a seat, and become foreign minister. People who were present, however, came away with different views of how realistic that idea was in practice.

Sacha had close connections to older Liberals across the country. He also had strong opinions about foreign affairs and had been critical of Israel’s human rights record, which, the professionals feared, would open a political vulnerability on an issue they didn’t need. But he was politically astute, with sharp observations, for instance, about Chrétien’s political machine in Quebec.

“The thing I remember most was how impressive Sacha was,” says Herle. “He seemed like a very sharp, practical tactician, hardball political operator. He was astute.” But the campaign already had a chief strategist, and it wasn’t Sacha. As such, “he didn’t look like a guy to me who was going to fall in line with whatever Gerry’s view were.”

The unstable dynamic continued until after Justin declared his candidacy for the Liberal leadership. Sacha was there to film the announcement, but his working relationship with Justin was becoming increasingly strained. They argued repeatedly over the French in his launch speech, having “epic dust-ups” past the point, professionals thought, that it made sense to be discussing it.

Soon afterward, Sacha was in Ottawa for a dinner with senior Liberals at Mamma Teresa, the old-fashioned Italian restaurant where for decades the people who run the country have been conspiring over linguine alle vongole. Dominic LeBlanc, whose father, Roméo, had been Pierre Trudeau’s governor general and who had babysat both boys, was telling people that Liberals were about to pick “the wrong Trudeau,” pointing out that Pierre had made Sacha, not Justin, executor of his estate. Word of LeBlanc’s warning got back to Butts, who called him to ask him to stop saying that, which he did.

The two Trudeaus could not get along, and, in the end, Justin had to proceed without Sacha. “I think it put a substantial amount of strain on the brothers, as you would expect, and I think they agreed it wasn’t worth it,” says a friend. “Justin needed a brother more than he needed another advisor.”

Sacha was grumpy about the split. He mostly stays out of the news but is reputed to be critical of the government in private conversations. In his 2016 interview with Proudfoot, he said he couldn’t do what his brother is doing. “To a certain extent, I was ashamed of being a prince, and he’s embraced it, used it. The person I chose to be is the one who’s hitchhiking in the rain in January in Israel, trying to get work on a farm. It’s so much realer to me.” He offered a surprisingly grim take on his brother’s political success: “I’m not sure I agree with this turn in politics, but it certainly is the mainstay one—the movie-star politician is a formidable force in this kind of world. Maybe a dangerous one, in the long run.”

Justin never speaks about what must have been a painful family episode. He had found the ruthlessness necessary to proceed toward his goal. He was going to run for the leadership, and Sacha was not going to be part of the team.

1 FIGHTER

I didn’t fully understand the Justin Trudeau phenomenon when I arrived in the Montreal riding of Papineau on October 2, 2012, to cover the launch of his campaign for the leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada for the National Post.

I knew Trudeau was a celebrity who attracted attention wherever he went, but I was skeptical about his political future. It was hard to take him entirely seriously in those days. He had great hair, a famous name, and a friendly, open way with people, but he had no particular accomplishments for the job. He made jokes that weren’t funny, and when he talked about policy he often seemed like a poser, with convictions based on his own inclinations rather than a deep understanding of the issues. He looked like a charismatic lightweight, one of those characters who show up on the Hill, strut and fret for a season or two, and then wander off to a less demanding career. Politics, Max Weber wrote, is the “slow boring of hard boards.” Trudeau didn’t look like a slow borer of hard boards, unlike the other men he would face in Parliament if he won the leadership.

Stephen Harper, the incumbent Conservative prime minister, was an economist who had engineered the merger of the Canadian Alliance and the Progressive Conservatives. Through patience, ruthlessness, and guile, he had won three elections in a row—two minorities, in 2006 and 2008, and finally a majority in 2011. By the autumn of 2012, his government was fading in the polls, but he was serious. So was his chief tormentor, New Democratic Party leader Thomas Mulcair, a lawyer and former Quebec Liberal Cabinet minister who had been elected leader after the death of the popular Jack Layton. The interim leader of the Liberals, lawyer Bob Rae, the former NDP premier of Ontario and a talented off-the-cuff speaker with a deep understanding of Canadian politics, was of similar stature.

Trudeau, in contrast, was a former high-school teacher. He had never served as a minister and had made little impression in his four years sitting on the backbench amid the third party in the House of Commons. But there was more to him than his weak resumé. He was famous. In a Parliament of drudges, full of former mayors, car dealers, and immigration lawyers, Trudeau stood out like a red rose on a grey suit lapel. He was young and handsome. He wore flip-flops and skateboarded to the Hill. When he entered a room, people said, “Hey! There’s Justin!”

I first met him in Darcy McGee’s, an Irish pub on the corner of Sparks and Elgin Streets, before he was elected to Parliament in 2008. I was then Ottawa bureau chief for the Halifax Chronicle Herald and often went to Darcy’s, a gathering place for political staffers, journalists, and lobbyists. Trudeau, who was known only as the flamboyant son of our former prime minister Pierre Trudeau, came in with his friend Gerry Butts, a hulking, bearded Cape Bretoner. I knew Trudeau was a quasi celebrity, and already there was speculation that he might one day run for office. A network of highly placed people associated with Trudeau père were rumoured to be waiting for the day when another Trudeau was ready to seek office.

I struck up a conversation with Justin and, at some point, mentioned his father in passing. “That’s weird,” I said. “I just realized I’m talking about your dad.”

He looked at me, squaring his shoulders. “Oh,” he said, “I never forget I’m a Trudeau.” He looked confident, poised, his eyes fixed. Huh, I thought. He’s like a prince.

Over the next couple of years, I had a few beers with him. He was friendly and chatty and, without making the slightest effort, was always the centre of attention. Almost everyone found it exciting to be around him. He has been famous since birth, the first child of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and the beautiful Margaret Sinclair. That was the X factor that made his candidacy remotely plausible, that made him a wild card entering the deck on that October day in 2012 when he took the stage in Papineau.

The speech he gave that night in Papineau did little to explain why he wanted to lead the party or why the party should lead the country. He praised Canada, the Liberal Party, progress, national unity, diversity, the environment, youth, and First Nations, and promised to work for the middle class. In the Globe and Mail, Daniel Leblanc described the speech as laying out an “ambitious but vague agenda.” The only substantial point was his personal relationship to Canadians. “Think about it for a moment: when was the last time you had a leader you actually trusted? And not just the nebulous ‘trust to govern competently’ but… the way you trust a friend to pick up your kids from school, or a neighbour to keep your extra front door key? That’s a respect that has to be earned, step by step.” Trudeau argued that Canadians knew him. “I feel so privileged to have had the relationship I’ve had, all my life, with this country, with its land, and with its people,” he said. “We’ve travelled many miles together, my friends. You have always been there for me.”

Later I spoke with Butts, expressing mild skepticism about Trudeau. He laughed and assured me Trudeau’s name recognition was likely “the highest for a leadership candidate in the history of the country.” What I didn’t know, but he did, was that Canadians wanted Trudeau to be prime minister. “The positive vibe that people have about him shows they’re not satisfied with what they have in leadership and they’re hoping for something more. In that sense, it has nothing to do with him and his personal attributes other than a kind of positive feeling they attribute to him. And our job, and his job, is to work our collective arses off to show people that he can be about something more.”

Butts had already been working his arse off on the project. “The Trudeau organization starts with one person, Gerald Butts,” says David Herle, a pollster and strategist Butts had recruited to the cause. Another insider called Butts the “mastermind” behind it all: “The thing that impressed me most about him was just his Rolodex. I’ve literally never seen anybody who was so good at accumulating friends and contacts, internationally, across the country, in this town, wherever. There’s just one guy. He’s got some kind of supernatural skill, finding powerful people and getting close with them.”

“Gerry is my best friend,” Trudeau told Leblanc in 2013. “He and I have been talking about the possibility and the potential of politics all my life.”

Butts is the son of a coal miner and a nurse from Glace Bay, a gritty working-class town near Sydney, Nova Scotia. When he was eight, the coal mine blew up, killing ten men and throwing everyone else out of work. The steel industry in nearby Sydney was slowly dying, and the moratorium on cod fishing was undercutting the fish-processing industry. There were too many people and not enough jobs. Politically, the area has always been left wing, influenced by the Antigonish Movement—a Catholic social justice movement that encouraged poor workers to organize co-operatives and credit unions. It was a place of strident unionism, patronage politics, hard drinking, Export A cigarettes, Celtic music, and working-class solidarity. Rather than following his classmates to St. Francis Xavier University, in nearby Antigonish, Butts, a promising student, went to McGill to study physics. He changed gears eventually and studied literature, doing his thesis on James Joyce’s Ulysses. In the debating club, he met Trudeau, who was then leery of introducing himself by his real name. He called himself Jason Tremblay and revealed his true identity only after he formed a favourable judgment of Butts. They bonded on the debating circuit, became fast friends.

After university, Butts cut his teeth working for Allan J. MacEachen, the Celtic Sphinx, a legendary Cape Breton political mastermind who helped engineer Pierre Trudeau’s 1980 election victory. He did research for MacEachen’s memoirs, which gave him insight into the history of the party. Angered by the Progressive Conservative government of Mike Harris in Ontario, Butts went to work for the provincial Liberals, eventually becoming principal secretary to Premier Dalton McGuinty, helping to engineer two election victories for him and developing a reputation for political acumen.

Butts and Trudeau had an unusually close relationship. “They didn’t work together,” says Herle. “They were together. They were friends, as thick as thieves, vacationed together, planned this project together.”

JUSTIN PIERRE JAMES TRUDEAU was born on Christmas Day in 1971, less than a year after his father, Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, married Margaret Sinclair, a “flower child” twenty-nine years his junior.I Although Justin grew up in the lap of luxury, with chauffeurs, servants, and global travel, his childhood was traumatic.

The Trudeaus lived at 24 Sussex Drive, the prime ministerial residence overlooking the Ottawa River. In 1973, Margaret gave birth to Alexandre “Sacha” Trudeau—another son born on Christmas Day—and in 1975 to Michel, who died tragically in an avalanche in British Columbia in 1998. The artistic and adventurous Margaret was then unaware she was suffering from bipolar disorder, a psychological condition that leads to manic episodes followed by paralyzing depression. She found life at the residence oppressive, and the marriage broke down in spectacular fashion in 1977.