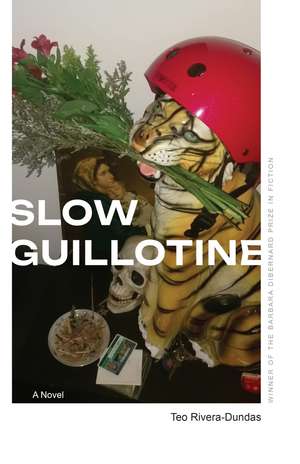

Slow Guillotine: A Novel: Zero Street Fiction

Autor Teo Rivera-Dundasen Limba Engleză Paperback – mar 2026

Slow Guillotine follows three broke weirdos whose collective desire to make and think about art is constantly interrupted by their art-industry-adjacent minimum-wage jobs. Throughout the novel, the three friends’ day jobs in a failing independent bookstore, a sterile gallery in downtown Manhattan, and miscellaneous living rooms across the Long Island birthday-party-clown circuit interweave with their attempts to come to terms with their precarity, gender-dysphoric embodiment, and the floating dream of collective liberation.

Spanning one year and told through an obsessive first-person present tense, Slow Guillotine brings the bildungsroman structure through the autofictional looking glass, questioning how “coming of age” could be feasible in a society of debtors, wage laborers, and renters.

Preț: 110.90 lei

Precomandă

Puncte Express: 166

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.60€ • 23.06$ • 17.11£

19.60€ • 23.06$ • 17.11£

Carte nepublicată încă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781496247315

ISBN-10: 1496247310

Pagini: 220

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Seria Zero Street Fiction

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1496247310

Pagini: 220

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Seria Zero Street Fiction

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Teo Rivera-Dundas is a writer in western Massachusetts. His work has received support from the Wassaic Project, Anderson Center at Tower View, California Institute of the Arts, and the University of California, San Diego. His writing has appeared in Gulf Coast, Meridian, Tupelo Quarterly, and Desperate Literature’s annual Eleven Stories anthology, among other publications.

Extras

Ten Notes about Work

before We Can Get Started

1.

Here are the types of packing material: bubble wrap, butcher paper

scraps, wiggly cardboard scraps, packing peanuts (blue polystyrene),

packing peanuts (biodegradable thermoplastic starch, a corn derivative,

edible), and weird bone-or meat-cross-section-looking

cardboard chunks. Also there’s the filler Hachette Book Group sends

with their cookbooks, a solid foam in the perfect negative space

shape of whatever was—or wasn’t, I guess—in the box. These are

uncanny, art object-type pieces, basically useless unless you’re prepared

to pack an outgoing shipment the exact size and shape of the

negative space foam. We throw this (nonbiodegradable, immortal)

foam away, and try not to think about it.

Hachette happens to be the least evil of the five big publisher-distributors,

apart from their use of hyperobject packing filler. I

learn this from Dima. HarperCollins is owned by Rupert Murdoch,

Simon and Schuster is Viacom, Penguin Random House is an endlessly

consumptive monopoly blob, and Macmillan Publishing Services

is some inscrutable British company that Dima tells me has

ties to weapons manufacturing. Is this actually true? I don’t know.

2.

I really like books. Ford hired me for the receiving room after I

told him so. I wanted to work the sales floor, as a regular bookseller,

but the back room had an opening and I needed the job. Now

I internalize corporate gossip, shipping and receiving jargon—I

guess knowing all this can become a kind of skill, or hobby, eventually,

too.

3.

Within the packing material, the book. Beyond the receiving room,

the bookstore.

4.

Today, it’s me and Arthur. Arthur is singing.

I grip the tape roller with both hands. He sings, but his voice

has nowhere to land. It rummages through the receiving room and

crashes, flailing, onto the floor. I grip the blue plastic handle of the

tape roller, which is indented at the fingers, with both hands. {~?~:

Repetition of “with both hands” intentional? Or consider cutting

the first sentence and retaining this one.}{~?~: yes, intentional! }

The in-progress box I hold between my legs. My feet I plant on the

floor, knees buckling against the standing desk.

The sound made by the tape roller as it peels over a cardboard

box’s two central flaps. The long pull of plastic, then a rip. Arthur

shelves the returns. Music plays over his singing. The two songs—one

from the speakers above my computer and the other issuing out

of Arthur’s mouth—have, as far as I can tell, decoupled.

I finish the last box and heave it to the top of its pile. When the

next load comes in I’ll slice each box open one at a time, keeping it

down with my legs. And if Arthur is still singing then I will hold

the boxcutter with both hands.

5.

Maybe this is the wrong way to start. I am not actually going to

freak out and attack Arthur with a boxcutter or anything. All I

mean to say is that my attention looks for something to hold onto,

moments like these. Arthur and I share the room. We perform

the same two or three tasks for eight hours at a time, unmediated

by conversation or any mutual interest in one another. I lift fifty-pound

boxes with my back. I take a fifteen-minute break on the

curb and return inside. Such conditions produce either trance or

obsession. Small things expand. It’s a phenomenon I’m tracking,

starting now.

The punch clock, the two computers at their standing desks,

the point-of-sale and inventory software. Last year’s calendar open

to next month.

A system of ropes hugs the receiving room ceiling, keeping a mass

of trash bags loaded with packing material in declining blobs above

us. Every day either I or Arthur or Dima (who’s still out) will fill a

trash bag with packing material from incoming shipments, hoist

the bag into the rope netting zone, and then take it down again a

few hours later, using its packing material to stuff outgoing shipments.

But because we end up collecting more material than we

use, the ceiling is constantly, slowly, lowering.

6.

Ford calls. He needs Arthur downstairs for shelving. “Good,” I say,

and send him down.

Dima is still out. Yesterday he called from Moscow and told me

about a pro-government demonstration that ended in a big roundup

of imported cheese being run over by a tank or a bulldozer or something.

He said this happened right in the central revolutionary

square, people throwing their Western cheese products into a grow-

ing pile, and that it was staged as a spontaneous patriotic thing but

was in fact a minor government operation meant to foment anti-nato

sentiment. I asked him why cheese, but he just described the

way the pile looked after getting steamrolled: flat brie, listen, flat

thin dirty bleu, dirty cheese, but paper cheese . . .

Dima is the one who taught me about certain packing peanuts

being edible. You can also lick them at the ends and stick them

together, and because they’re weightless you can assemble surprisingly

large packing peanut sculptures this way. It’s all cornstarch.

7.

Someone has rolled in the day’s returns using one of the red handcarts

they have out on the sales floor.

Before he left, Dima trained me to file returns. Here’s how it

works: sort every book by distributor, stacking each title on the

shelves labeled prh or ss or whatever, respectively. Vintage is Penguin,

Tor is mps, New Directions is Norton, Coffee House is Perseus,

Anchor is Penguin, Norton is Norton, fsg is mps, Archipelago

is Penguin, Melville House is Penguin, tiny presses are usually spd,

Chicago is Chicago, Columbia is Wiley, Scholastic is Scholastic,

Vintage is Penguin again, Graywolf is mps, Scribner is Simon, Ecco

is Harper, Harper is Harper, Knopf is Penguin, Puffin is Penguin,

Random House is Penguin, Penguin is Penguin.

These, and a few dozen adult coloring books at the bottom of my

handcart. That has to be a mistake—Ford recently implemented a

“buy a coloring book get My Brilliant Friend half off” special that

became so popular he had to discontinue it. People started returning

My Brilliant Friend for full store credit just to turn around and

buy another coloring book, essentially for free.

I draw a question mark on a pink Post-it, slap this to the topmost

coloring book, and stack.

8.

Ford is about to walk into the room and say something. I can feel

it. He’s about to stride his seven-foot-tall leatherette mass in here

and say listen we need to think about how we proceed with X or Y

folks it’s important. He’ll say folks even though he’s talking just to

me. Ford’s green voice and boat shoes. In his office there are two

books about how to build a yacht, up on a shelf twelve feet off the

ground. Do you build them from scratch or what?

Here he comes. The year is 2014, or it’s 2015—it doesn’t matter,

either works. Ford crams his massive face into the room. “Milton is

on his way,” he says. Then he eyes the coloring books on the return

stack and stoops over, rapping them with his enormous knuckles.

“You are not just blithely returning adult coloring books right

now, folks,” he says. “We need to think about how we work. These

should’ve been at the registers yesterday.”

He looks at the return pile, looks at me looking at him, then

looks at the drooping penis statue Dima made out of licked-together

packing peanuts just before he left. “For God’s sake,” Ford says.

9.

An hour or so later the intrastore phone rings: Milton’s here. I tell

Ford to give me Arthur back, and then I pull the convertible hand

truck from under my standing desk and roll it to the elevator. At the

curb, there’s Milton, perched against his double-parked

minivan, smoking. He hands me a cigarette, and a minute later we’re hauling

boxes from his minivan onto the hand truck.

When I first started, Dima explained the Milton situation. Let’s

say you knew a guy, call him Philton, who works at one of the major

book distribution warehouses. Alright. Say every now and again,

maybe every three weeks, a pallet of boxes of books fell off this guy’s

truck. Well, the distributor who owns the warehouse—especially

a distributor major enough to have multiple warehouses, shipping,

say, global quantities of science fiction trade paperbacks—well,

they barely notice when stock goes missing, or so says Milton, or so says

Ford, according to Dima. And if a couple hundred sci-fi

paperbacks with titles like Perihelion Uprising and Ninth Fae: A Gereon Ëxter

Novel end up in our return pool, then, well, such an enormous distributor

would happily pay us to have these back, this kind of thing

happens all the time, and if we make a few thousand dollars on the

side returning inventory we never had to buy in the first place, great.

By we, of course, I mean the store. Milton gets his cut.

It’s the least he can do to share his shitty Camels with me as we

lift fifty-pound boxes, one after the other, onto a small mountain

on the hand truck.

When we finish, Milton asks if I’ve met any special ladies in the

Big Apple. I tell him I have, and that I am in love. Then Milton

does a thing where he looks at me, adjusts his crotch, says alright

then boss, and drives away.

10.

By the time I’ve wheeled the boxes past the front registers—past

New Releases and milling customers side-eyeing tote bags, into a

three-point reversal to fit diagonally in the elevator, up the elevator,

past the second floor information desk and buyback booth, past

Middle Readers and Young Adult, and into the receiving room—by

the time this is done, Arthur has cleared an area for me by the

standing desks and waits with his arms out for the boxes. I heave

them at him, lifting with my back. He catches and stacks.

I plant my feet on the floor and flick open a boxcutter, keeping

the first box in place with my legs as I slice it open. The bubble wrap

I tear from the box and stuff into an in-progress trash bag, which

quickly fills. I toss the bag to Arthur, who hoists it into the netting

zone above us. The ceiling lowers. Each book has to be individually

scanned into the point-of-sale and inventory software, which,

because these are Milton-ass sci-fi trade paperbacks, the majority

of them don’t show up in the store’s system and we have to do data

input manually. The process takes forever and is why, before he

left to visit his dad in Moscow, Dima changed the receiving room

computers’ passwords to fuckmilton. I boot mine up and put on

the song of the summer, which is twenty minutes long and will

forever represent my moving to the Big Apple and falling in love.

Arthur, who has never heard this song in his life, begins to sing.

Alright then boss. We scan. With everything scanned in, we start

the return, which is going to Macmillan Publishing Services. We

launder the stolen sci-fi with actual stock from the return shelves.

Minotaur is mps, Forge is mps, Picador is mps, Starscape is mps,

Graywolf is mps, Tor is mps. Arthur, neck jutting back and forth

with the music, pulls a trash bag down from the ceiling and tears

out a long bunch of butcher paper. I fill a box, holding it in place

with my legs, and Arthur stuffs its negative space with paper. A

good box you should be able to stand on no problem, no bowing

with your weight or anything like that. I tape the box shut using

the tape roller, which is blue plastic, indented at the fingers, a perfect

negative space shape for the thin layer of skin holding back my

blood, and which I hold with both hands.

before We Can Get Started

1.

Here are the types of packing material: bubble wrap, butcher paper

scraps, wiggly cardboard scraps, packing peanuts (blue polystyrene),

packing peanuts (biodegradable thermoplastic starch, a corn derivative,

edible), and weird bone-or meat-cross-section-looking

cardboard chunks. Also there’s the filler Hachette Book Group sends

with their cookbooks, a solid foam in the perfect negative space

shape of whatever was—or wasn’t, I guess—in the box. These are

uncanny, art object-type pieces, basically useless unless you’re prepared

to pack an outgoing shipment the exact size and shape of the

negative space foam. We throw this (nonbiodegradable, immortal)

foam away, and try not to think about it.

Hachette happens to be the least evil of the five big publisher-distributors,

apart from their use of hyperobject packing filler. I

learn this from Dima. HarperCollins is owned by Rupert Murdoch,

Simon and Schuster is Viacom, Penguin Random House is an endlessly

consumptive monopoly blob, and Macmillan Publishing Services

is some inscrutable British company that Dima tells me has

ties to weapons manufacturing. Is this actually true? I don’t know.

2.

I really like books. Ford hired me for the receiving room after I

told him so. I wanted to work the sales floor, as a regular bookseller,

but the back room had an opening and I needed the job. Now

I internalize corporate gossip, shipping and receiving jargon—I

guess knowing all this can become a kind of skill, or hobby, eventually,

too.

3.

Within the packing material, the book. Beyond the receiving room,

the bookstore.

4.

Today, it’s me and Arthur. Arthur is singing.

I grip the tape roller with both hands. He sings, but his voice

has nowhere to land. It rummages through the receiving room and

crashes, flailing, onto the floor. I grip the blue plastic handle of the

tape roller, which is indented at the fingers, with both hands. {~?~:

Repetition of “with both hands” intentional? Or consider cutting

the first sentence and retaining this one.}{~?~: yes, intentional! }

The in-progress box I hold between my legs. My feet I plant on the

floor, knees buckling against the standing desk.

The sound made by the tape roller as it peels over a cardboard

box’s two central flaps. The long pull of plastic, then a rip. Arthur

shelves the returns. Music plays over his singing. The two songs—one

from the speakers above my computer and the other issuing out

of Arthur’s mouth—have, as far as I can tell, decoupled.

I finish the last box and heave it to the top of its pile. When the

next load comes in I’ll slice each box open one at a time, keeping it

down with my legs. And if Arthur is still singing then I will hold

the boxcutter with both hands.

5.

Maybe this is the wrong way to start. I am not actually going to

freak out and attack Arthur with a boxcutter or anything. All I

mean to say is that my attention looks for something to hold onto,

moments like these. Arthur and I share the room. We perform

the same two or three tasks for eight hours at a time, unmediated

by conversation or any mutual interest in one another. I lift fifty-pound

boxes with my back. I take a fifteen-minute break on the

curb and return inside. Such conditions produce either trance or

obsession. Small things expand. It’s a phenomenon I’m tracking,

starting now.

The punch clock, the two computers at their standing desks,

the point-of-sale and inventory software. Last year’s calendar open

to next month.

A system of ropes hugs the receiving room ceiling, keeping a mass

of trash bags loaded with packing material in declining blobs above

us. Every day either I or Arthur or Dima (who’s still out) will fill a

trash bag with packing material from incoming shipments, hoist

the bag into the rope netting zone, and then take it down again a

few hours later, using its packing material to stuff outgoing shipments.

But because we end up collecting more material than we

use, the ceiling is constantly, slowly, lowering.

6.

Ford calls. He needs Arthur downstairs for shelving. “Good,” I say,

and send him down.

Dima is still out. Yesterday he called from Moscow and told me

about a pro-government demonstration that ended in a big roundup

of imported cheese being run over by a tank or a bulldozer or something.

He said this happened right in the central revolutionary

square, people throwing their Western cheese products into a grow-

ing pile, and that it was staged as a spontaneous patriotic thing but

was in fact a minor government operation meant to foment anti-nato

sentiment. I asked him why cheese, but he just described the

way the pile looked after getting steamrolled: flat brie, listen, flat

thin dirty bleu, dirty cheese, but paper cheese . . .

Dima is the one who taught me about certain packing peanuts

being edible. You can also lick them at the ends and stick them

together, and because they’re weightless you can assemble surprisingly

large packing peanut sculptures this way. It’s all cornstarch.

7.

Someone has rolled in the day’s returns using one of the red handcarts

they have out on the sales floor.

Before he left, Dima trained me to file returns. Here’s how it

works: sort every book by distributor, stacking each title on the

shelves labeled prh or ss or whatever, respectively. Vintage is Penguin,

Tor is mps, New Directions is Norton, Coffee House is Perseus,

Anchor is Penguin, Norton is Norton, fsg is mps, Archipelago

is Penguin, Melville House is Penguin, tiny presses are usually spd,

Chicago is Chicago, Columbia is Wiley, Scholastic is Scholastic,

Vintage is Penguin again, Graywolf is mps, Scribner is Simon, Ecco

is Harper, Harper is Harper, Knopf is Penguin, Puffin is Penguin,

Random House is Penguin, Penguin is Penguin.

These, and a few dozen adult coloring books at the bottom of my

handcart. That has to be a mistake—Ford recently implemented a

“buy a coloring book get My Brilliant Friend half off” special that

became so popular he had to discontinue it. People started returning

My Brilliant Friend for full store credit just to turn around and

buy another coloring book, essentially for free.

I draw a question mark on a pink Post-it, slap this to the topmost

coloring book, and stack.

8.

Ford is about to walk into the room and say something. I can feel

it. He’s about to stride his seven-foot-tall leatherette mass in here

and say listen we need to think about how we proceed with X or Y

folks it’s important. He’ll say folks even though he’s talking just to

me. Ford’s green voice and boat shoes. In his office there are two

books about how to build a yacht, up on a shelf twelve feet off the

ground. Do you build them from scratch or what?

Here he comes. The year is 2014, or it’s 2015—it doesn’t matter,

either works. Ford crams his massive face into the room. “Milton is

on his way,” he says. Then he eyes the coloring books on the return

stack and stoops over, rapping them with his enormous knuckles.

“You are not just blithely returning adult coloring books right

now, folks,” he says. “We need to think about how we work. These

should’ve been at the registers yesterday.”

He looks at the return pile, looks at me looking at him, then

looks at the drooping penis statue Dima made out of licked-together

packing peanuts just before he left. “For God’s sake,” Ford says.

9.

An hour or so later the intrastore phone rings: Milton’s here. I tell

Ford to give me Arthur back, and then I pull the convertible hand

truck from under my standing desk and roll it to the elevator. At the

curb, there’s Milton, perched against his double-parked

minivan, smoking. He hands me a cigarette, and a minute later we’re hauling

boxes from his minivan onto the hand truck.

When I first started, Dima explained the Milton situation. Let’s

say you knew a guy, call him Philton, who works at one of the major

book distribution warehouses. Alright. Say every now and again,

maybe every three weeks, a pallet of boxes of books fell off this guy’s

truck. Well, the distributor who owns the warehouse—especially

a distributor major enough to have multiple warehouses, shipping,

say, global quantities of science fiction trade paperbacks—well,

they barely notice when stock goes missing, or so says Milton, or so says

Ford, according to Dima. And if a couple hundred sci-fi

paperbacks with titles like Perihelion Uprising and Ninth Fae: A Gereon Ëxter

Novel end up in our return pool, then, well, such an enormous distributor

would happily pay us to have these back, this kind of thing

happens all the time, and if we make a few thousand dollars on the

side returning inventory we never had to buy in the first place, great.

By we, of course, I mean the store. Milton gets his cut.

It’s the least he can do to share his shitty Camels with me as we

lift fifty-pound boxes, one after the other, onto a small mountain

on the hand truck.

When we finish, Milton asks if I’ve met any special ladies in the

Big Apple. I tell him I have, and that I am in love. Then Milton

does a thing where he looks at me, adjusts his crotch, says alright

then boss, and drives away.

10.

By the time I’ve wheeled the boxes past the front registers—past

New Releases and milling customers side-eyeing tote bags, into a

three-point reversal to fit diagonally in the elevator, up the elevator,

past the second floor information desk and buyback booth, past

Middle Readers and Young Adult, and into the receiving room—by

the time this is done, Arthur has cleared an area for me by the

standing desks and waits with his arms out for the boxes. I heave

them at him, lifting with my back. He catches and stacks.

I plant my feet on the floor and flick open a boxcutter, keeping

the first box in place with my legs as I slice it open. The bubble wrap

I tear from the box and stuff into an in-progress trash bag, which

quickly fills. I toss the bag to Arthur, who hoists it into the netting

zone above us. The ceiling lowers. Each book has to be individually

scanned into the point-of-sale and inventory software, which,

because these are Milton-ass sci-fi trade paperbacks, the majority

of them don’t show up in the store’s system and we have to do data

input manually. The process takes forever and is why, before he

left to visit his dad in Moscow, Dima changed the receiving room

computers’ passwords to fuckmilton. I boot mine up and put on

the song of the summer, which is twenty minutes long and will

forever represent my moving to the Big Apple and falling in love.

Arthur, who has never heard this song in his life, begins to sing.

Alright then boss. We scan. With everything scanned in, we start

the return, which is going to Macmillan Publishing Services. We

launder the stolen sci-fi with actual stock from the return shelves.

Minotaur is mps, Forge is mps, Picador is mps, Starscape is mps,

Graywolf is mps, Tor is mps. Arthur, neck jutting back and forth

with the music, pulls a trash bag down from the ceiling and tears

out a long bunch of butcher paper. I fill a box, holding it in place

with my legs, and Arthur stuffs its negative space with paper. A

good box you should be able to stand on no problem, no bowing

with your weight or anything like that. I tape the box shut using

the tape roller, which is blue plastic, indented at the fingers, a perfect

negative space shape for the thin layer of skin holding back my

blood, and which I hold with both hands.

Cuprins

Ten Notes About Work Before We Can Get Started

Another Note (To the Reader)

In the Summer We Are Inside Preparing Food

A Snake Appearing in Dreams

I Have Yet to Develop a Skincare Routine

Ten More Notes About Work

Still Winter

Look How Badly It Wants to Live

Weeks Not Months

Final Ten Notes About Work

Acknowledgments

Another Note (To the Reader)

In the Summer We Are Inside Preparing Food

A Snake Appearing in Dreams

I Have Yet to Develop a Skincare Routine

Ten More Notes About Work

Still Winter

Look How Badly It Wants to Live

Weeks Not Months

Final Ten Notes About Work

Acknowledgments

Recenzii

“Slow Guillotine’s subversive, heat-seeking pulse is defiantly pro-ennui, embracing projectile vomit and the thing we want most besides love, that is—language at the very edge, and the shedding of our perpetually too-snug skins.”—Jess Arndt, author of Large Animals: Stories

“An incisive, fluid, and absurdly funny portrait of both the bookselling industry and of what it’s like to try to piece a life together in Manhattan while young(ish) and poor. Whether talking about book-return scams, clowns, social media, cooking, the awfulness of searching for an apartment, tattooing, or pop-ups, Slow Guillotine is sharply observant as it eviscerates the movie myth of New York and replaces it with something less romantic but much more real, current, and painfully hilarious.”—Brian Evenson, author of Song for the Unraveling of the World

“Teo Rivera-Dundas makes the banal shine brilliantly—because when you’re young and in New York, geared with friendship, queerness, and art, even the most mundane trivialities can turn into bold misadventures. Slow Guillotine is a tender, slithering threat: hope hovering, ready to strike.”—Lily Hoang, author of A Bestiary

“An incisive, fluid, and absurdly funny portrait of both the bookselling industry and of what it’s like to try to piece a life together in Manhattan while young(ish) and poor. Whether talking about book-return scams, clowns, social media, cooking, the awfulness of searching for an apartment, tattooing, or pop-ups, Slow Guillotine is sharply observant as it eviscerates the movie myth of New York and replaces it with something less romantic but much more real, current, and painfully hilarious.”—Brian Evenson, author of Song for the Unraveling of the World

“Teo Rivera-Dundas makes the banal shine brilliantly—because when you’re young and in New York, geared with friendship, queerness, and art, even the most mundane trivialities can turn into bold misadventures. Slow Guillotine is a tender, slithering threat: hope hovering, ready to strike.”—Lily Hoang, author of A Bestiary

Descriere

Using humor and thoughtful poetics to examine the impact structural violence takes on the body, Slow Guillotine follows three broke weirdos whose collective desire to make and think about art is constantly interrupted by their art-industry-adjacent minimum-wage jobs.