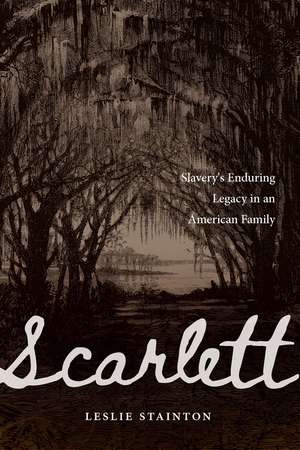

Scarlett: Slavery's Enduring Legacy in an American Family

Autor Leslie Staintonen Limba Engleză Hardback – noi 2025

At its core is the riddle of Stainton’s Georgia-born grandmother, Mary “Mamie” King Hilsman Pettigrew, who embraced the Lost Cause of the Confederacy but was tormented lifelong by her suspicion that Scarlett men had engaged in racial violence in the twentieth century. Mamie gave Stainton her copies of Gone with the Wind and Fanny Kemble’s 1863 Journal of a Resistance on a Georgia Plantation, one of the most explosive indictments of American slavery ever written. These books informed Stainton’s quest to discover the truth about her Scarlett ancestors and her grandmother’s nightmare vision of racial violence involving her family.

By threading the stories of Margaret Mitchell and Fanny Kemble through the narrative of her Scarlett forebears, Stainton raises critical questions about the choices Americans have made, then and now, that have cemented the nation’s complicity in slavery’s persistent legacy.

Preț: 186.58 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 280

Preț estimativ în valută:

33.02€ • 38.72$ • 28.100£

33.02€ • 38.72$ • 28.100£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 26 ianuarie-09 februarie

Livrare express 09-15 ianuarie pentru 93.68 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781640126756

ISBN-10: 1640126759

Pagini: 280

Ilustrații: 24 photographs, 1 genealogy, 1 map

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Editura: Potomac Books Inc

Colecția Potomac Books

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1640126759

Pagini: 280

Ilustrații: 24 photographs, 1 genealogy, 1 map

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Editura: Potomac Books Inc

Colecția Potomac Books

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Leslie Stainton has served on the board of directors of both the Slave Dwelling Project and Coming to the Table. She is a two-time Fulbright recipient and a former lecturer in creative nonfiction at the University of Michigan Residential College. Stainton is the author of Staging Ground: An American Theater and Its Ghosts and Lorca: A Dream of Life and has published essays in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the American Scholar, and other publications.

Extras

1

MIDNIGHT

Quiet at last. Just the flutter of leaves in the breeze outside and the sound

of my companions unfolding their sleeping gear. We’ve arranged our

belongings so as not to disturb the museum exhibit that occupies the

room by day. A gardening basket in one corner. A pine table set, as if for

breakfast, with two plates and a bowl. A massive brick hearth.

Except hearth isn’t quite the right word, not here at least. Not inside

this pine cabin on the Georgia coast, fifteen miles north of Brunswick.

As I unzip the sleeping bag I’ve borrowed from my stepson, it occurs to

me that nothing in this space is what it claims to be. Not the faux table

setting or the curtained windows or the wicker chair or the narrow cot

with the chenille spread and embroidered pillow in the pseudo-bedroom

to my left and not the sign outside on the path to the door: “Servants

Quarters.”

I know the kind of scene we’re meant to conjure: a plump Mammy

in a kerchief standing at the fireplace, stirring a pot of something while

children frolic on the floor behind her—the same pine floor where I’ve

laid out my make-believe bed on top of a yoga mat, which, I now realize,

does nothing to cushion my back against the hard wood planks.

It’s been decades since I’ve come this close to roughing it. I spent

the past two nights under a chintz duvet on a queen-sized canopy bed

in an air-conditioned Savannah hotel room. Before heading south on

I-95 today, I treated myself to lunch in the hotel restaurant, a restored

eighteenth-century tavern. Glass of sauvignon blanc, locally sourced

fried-green tomato sandwich with aioli, espresso.

I crawl inside the flannel interior of my camping gear and try to court

sleep, but I’m distracted by my two companions. Joe’s stretched out

behind me on the floor, posting updates to his Facebook page. Prinny’s

half-asleep beside me, breathing softly. It’s her tenth or eleventh overnight

in a cabin, and she’s got the drill down. Flashlight neatly positioned

on a nearby chair, on top of her neatly folded clothes. Thick foam pad

under her back.

I close my eyes and listen to the mournful pings of Joe’s phone as he

sends the last of his missives into the world. Then silence. The room

goes dark. Just the three of us arrayed like mannequins on a moonlit

stage set on the Georgia coast. This is why I came, isn’t it? Except I can’t

get comfortable. Roll to one side, yank at my T-shirt,

imagine I’m back home in Michigan with my husband.

“I don’t know why I’m doing this,” I snarled a week ago, as I stood

over my open suitcase, fretting.

“You’ll figure it out,” he said.

But I haven’t. Lying here, feigning sleep, my mind hurtles into its

familiar spin cycle. What if I’m awake all night? What if I step on a

snake on my way to the bathroom? There are rattlers on the plantation

grounds, alligators in the marshes where they used to grow rice. Ticks.

Spiders. Joe likes to tell about the time he woke in a cabin to find spiders

crawling all over him. He’s never seen a ghost on a sleepover, but

spiders, yes. They terrify him.

“You have to visit these places to see what they endured,” he said earlier

tonight in a talk to docents inside the visitors’ center of the plantation.

He wore narrow, wire-rimmed glasses and a collarless white shirt

under the thick blue wool uniform of a Union soldier. A dozen people,

all white, mostly retirees, sat attentively in rows of plastic chairs. On the

screen above his head, he unveiled slide after slide of the kinds of places

he meant: weatherbeaten shacks in Tennessee, wooden cabins in South

Carolina, a two-story brick tenement behind an urban mansion in North

Carolina, attic rooms in New York and Pennsylvania.

“Because they hung in there,” Joe said of the people who once lived

in these spaces, “we’re here today. African Americans. They acquiesced

because of us, their descendants. Anything beyond acquiescence could

be their death.”

This morning’s Georgia Times-Union had advertised his talk and our

overnight stay, noting that, as a descendant of enslavers from the region,

I’d be joining Joe McGill, founder of the Slave Dwelling Project, and

Prinny Anderson, a white descendant of Thomas Jefferson, on the latest

of Joe’s sleepovers in a slave dwelling, this one at the Hofwyl-Broadfield

State Historical Site in Glynn County. I was startled by the front-page

coverage, the realization that, without meaning to, I had exposed my

family—the distant cousins who don’t return my texts or emails when

I visit the area, the nameless person who planted a Confederate flag

in front of the granite obelisk that marks my ancestors’ cemetery in

Brunswick. “Sleepover Puts Spotlight on Glynn’s Slave-Holding

Past,” the Times-Union headline announced.

And now here I am, rolling onto my left side, scrunching the single

pillow I’ve remembered to bring with me, wondering how long my

bladder will hold out before I have to make my way in the dark with

Prinny’s flashlight to the bathroom that’s been installed on the other

side of the wall behind the fireplace, in another tiny space originally

built to house as many as twelve people. Who knows what I’ll trip over

on my way there? I’ve learned to step gingerly in this part of the world.

My grandmother, born in Brunswick in 1898, was taught as a child to

kill any snake she found that wasn’t poisonous and to call for an uncle

with a gun whenever she spotted one that was. In her seventies, on a

visit to the family homestead in the woods outside Brunswick, she nearly

stepped on a diamondback one day as she was getting out of her car.

She loved this hardscrabble strip of Atlantic coastline, halfway between

Jacksonville and Savannah. Although she and my grandfather retired to

a small town in tidewater Virginia, she never reconciled herself to the

place. “Virginia is as far north as I will ever go,” she declared and pressed

her tiny foot into the carpet as if to mark a line.

She had a bird’s beaked nose and mouth and wore her hair in long,

graying ropes looped around her skull. She dressed in brown or at most

a drab olive. Much of the time she terrified me: the stern reminders to

buckle my seatbelt, the drumbeat of her shoes climbing the stairs to

inform me of yet another unwitting household infraction. The stories

of ancestral hardship meant to show me how good I had it. The Scarlett

O’Hara prettiness of what life was like before the war versus the shabbiness

of what came after. Her own widowed mother, forced to open a

boardinghouse and take in strangers to make ends meet.

Mary King Hilsman Pettigrew, my maternal grandmother—whom

we called “Mamie.” She’s the reason I’m here tonight, twenty minutes

up the highway from her birthplace. She’s the one who insisted I know

the kind of people I came from: strong people—strong

women in particular. Like my grandmother herself, who knew more about roughing

it than I’d ever learn. She spent twenty years living in the Caribbean

with my Navy-officer grandfather, braving scorpions and malaria while

raising three children. At the end of it all she only wanted more—more

island sunsets and patois songs, more solitary rambles in the countryside

searching for pre-Columbian relics. My grandmother, the excavator.

Except when it came to our family. She and her sisters devoted years

to assembling the ancestral story, compiling photos, deciphering letters,

filling in cemetery maps and genealogical charts. It was no secret we

had “owned slaves,” as they put it. But it wasn’t something they dwelt

on. “There are things we don’t talk about,” Mamie said briskly and often.

Little room in this scenario for what I’m doing tonight. My grandmother

would have winced at this morning’s front-page coverage. She

and her sisters gave their share of interviews to the local press, but always

with an emphasis on the salutary: the family patriarch, Francis Muir

Scarlett, a penniless British immigrant who made his way to Georgia

as a teenager in the late eighteenth century and became one of Glynn

County’s richest planters; his eleven exemplary children; their illustrious

twentieth-century heirs.

And the story everyone liked best: the coincidence that Margaret

Mitchell chose our family name for her infamous heroine.

Born in the last years of the nineteenth century and raised on the same

postwar brew of recrimination and regret that nourished Mitchell, my

grandmother Mamie could not forget. “It still makes me angry at the

Yankees stripping the Southern families,” she said in her late seventies.

She preferred the golden age that preceded her birth, the years when the

family fields stretched to the edge of the ocean that spelled misery to

millions and wealth to us, when palmettoes shimmered in the twilight,

and blushing belles cavorted with suitors at parties like the ones Scarlett

O’Hara attended, she who carried our name.

MIDNIGHT

Quiet at last. Just the flutter of leaves in the breeze outside and the sound

of my companions unfolding their sleeping gear. We’ve arranged our

belongings so as not to disturb the museum exhibit that occupies the

room by day. A gardening basket in one corner. A pine table set, as if for

breakfast, with two plates and a bowl. A massive brick hearth.

Except hearth isn’t quite the right word, not here at least. Not inside

this pine cabin on the Georgia coast, fifteen miles north of Brunswick.

As I unzip the sleeping bag I’ve borrowed from my stepson, it occurs to

me that nothing in this space is what it claims to be. Not the faux table

setting or the curtained windows or the wicker chair or the narrow cot

with the chenille spread and embroidered pillow in the pseudo-bedroom

to my left and not the sign outside on the path to the door: “Servants

Quarters.”

I know the kind of scene we’re meant to conjure: a plump Mammy

in a kerchief standing at the fireplace, stirring a pot of something while

children frolic on the floor behind her—the same pine floor where I’ve

laid out my make-believe bed on top of a yoga mat, which, I now realize,

does nothing to cushion my back against the hard wood planks.

It’s been decades since I’ve come this close to roughing it. I spent

the past two nights under a chintz duvet on a queen-sized canopy bed

in an air-conditioned Savannah hotel room. Before heading south on

I-95 today, I treated myself to lunch in the hotel restaurant, a restored

eighteenth-century tavern. Glass of sauvignon blanc, locally sourced

fried-green tomato sandwich with aioli, espresso.

I crawl inside the flannel interior of my camping gear and try to court

sleep, but I’m distracted by my two companions. Joe’s stretched out

behind me on the floor, posting updates to his Facebook page. Prinny’s

half-asleep beside me, breathing softly. It’s her tenth or eleventh overnight

in a cabin, and she’s got the drill down. Flashlight neatly positioned

on a nearby chair, on top of her neatly folded clothes. Thick foam pad

under her back.

I close my eyes and listen to the mournful pings of Joe’s phone as he

sends the last of his missives into the world. Then silence. The room

goes dark. Just the three of us arrayed like mannequins on a moonlit

stage set on the Georgia coast. This is why I came, isn’t it? Except I can’t

get comfortable. Roll to one side, yank at my T-shirt,

imagine I’m back home in Michigan with my husband.

“I don’t know why I’m doing this,” I snarled a week ago, as I stood

over my open suitcase, fretting.

“You’ll figure it out,” he said.

But I haven’t. Lying here, feigning sleep, my mind hurtles into its

familiar spin cycle. What if I’m awake all night? What if I step on a

snake on my way to the bathroom? There are rattlers on the plantation

grounds, alligators in the marshes where they used to grow rice. Ticks.

Spiders. Joe likes to tell about the time he woke in a cabin to find spiders

crawling all over him. He’s never seen a ghost on a sleepover, but

spiders, yes. They terrify him.

“You have to visit these places to see what they endured,” he said earlier

tonight in a talk to docents inside the visitors’ center of the plantation.

He wore narrow, wire-rimmed glasses and a collarless white shirt

under the thick blue wool uniform of a Union soldier. A dozen people,

all white, mostly retirees, sat attentively in rows of plastic chairs. On the

screen above his head, he unveiled slide after slide of the kinds of places

he meant: weatherbeaten shacks in Tennessee, wooden cabins in South

Carolina, a two-story brick tenement behind an urban mansion in North

Carolina, attic rooms in New York and Pennsylvania.

“Because they hung in there,” Joe said of the people who once lived

in these spaces, “we’re here today. African Americans. They acquiesced

because of us, their descendants. Anything beyond acquiescence could

be their death.”

This morning’s Georgia Times-Union had advertised his talk and our

overnight stay, noting that, as a descendant of enslavers from the region,

I’d be joining Joe McGill, founder of the Slave Dwelling Project, and

Prinny Anderson, a white descendant of Thomas Jefferson, on the latest

of Joe’s sleepovers in a slave dwelling, this one at the Hofwyl-Broadfield

State Historical Site in Glynn County. I was startled by the front-page

coverage, the realization that, without meaning to, I had exposed my

family—the distant cousins who don’t return my texts or emails when

I visit the area, the nameless person who planted a Confederate flag

in front of the granite obelisk that marks my ancestors’ cemetery in

Brunswick. “Sleepover Puts Spotlight on Glynn’s Slave-Holding

Past,” the Times-Union headline announced.

And now here I am, rolling onto my left side, scrunching the single

pillow I’ve remembered to bring with me, wondering how long my

bladder will hold out before I have to make my way in the dark with

Prinny’s flashlight to the bathroom that’s been installed on the other

side of the wall behind the fireplace, in another tiny space originally

built to house as many as twelve people. Who knows what I’ll trip over

on my way there? I’ve learned to step gingerly in this part of the world.

My grandmother, born in Brunswick in 1898, was taught as a child to

kill any snake she found that wasn’t poisonous and to call for an uncle

with a gun whenever she spotted one that was. In her seventies, on a

visit to the family homestead in the woods outside Brunswick, she nearly

stepped on a diamondback one day as she was getting out of her car.

She loved this hardscrabble strip of Atlantic coastline, halfway between

Jacksonville and Savannah. Although she and my grandfather retired to

a small town in tidewater Virginia, she never reconciled herself to the

place. “Virginia is as far north as I will ever go,” she declared and pressed

her tiny foot into the carpet as if to mark a line.

She had a bird’s beaked nose and mouth and wore her hair in long,

graying ropes looped around her skull. She dressed in brown or at most

a drab olive. Much of the time she terrified me: the stern reminders to

buckle my seatbelt, the drumbeat of her shoes climbing the stairs to

inform me of yet another unwitting household infraction. The stories

of ancestral hardship meant to show me how good I had it. The Scarlett

O’Hara prettiness of what life was like before the war versus the shabbiness

of what came after. Her own widowed mother, forced to open a

boardinghouse and take in strangers to make ends meet.

Mary King Hilsman Pettigrew, my maternal grandmother—whom

we called “Mamie.” She’s the reason I’m here tonight, twenty minutes

up the highway from her birthplace. She’s the one who insisted I know

the kind of people I came from: strong people—strong

women in particular. Like my grandmother herself, who knew more about roughing

it than I’d ever learn. She spent twenty years living in the Caribbean

with my Navy-officer grandfather, braving scorpions and malaria while

raising three children. At the end of it all she only wanted more—more

island sunsets and patois songs, more solitary rambles in the countryside

searching for pre-Columbian relics. My grandmother, the excavator.

Except when it came to our family. She and her sisters devoted years

to assembling the ancestral story, compiling photos, deciphering letters,

filling in cemetery maps and genealogical charts. It was no secret we

had “owned slaves,” as they put it. But it wasn’t something they dwelt

on. “There are things we don’t talk about,” Mamie said briskly and often.

Little room in this scenario for what I’m doing tonight. My grandmother

would have winced at this morning’s front-page coverage. She

and her sisters gave their share of interviews to the local press, but always

with an emphasis on the salutary: the family patriarch, Francis Muir

Scarlett, a penniless British immigrant who made his way to Georgia

as a teenager in the late eighteenth century and became one of Glynn

County’s richest planters; his eleven exemplary children; their illustrious

twentieth-century heirs.

And the story everyone liked best: the coincidence that Margaret

Mitchell chose our family name for her infamous heroine.

Born in the last years of the nineteenth century and raised on the same

postwar brew of recrimination and regret that nourished Mitchell, my

grandmother Mamie could not forget. “It still makes me angry at the

Yankees stripping the Southern families,” she said in her late seventies.

She preferred the golden age that preceded her birth, the years when the

family fields stretched to the edge of the ocean that spelled misery to

millions and wealth to us, when palmettoes shimmered in the twilight,

and blushing belles cavorted with suitors at parties like the ones Scarlett

O’Hara attended, she who carried our name.

Cuprins

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

List of Abbreviations

Note on Language

Before

Part 1. Myth

1. Midnight

2. The Family Album

3. Fanny Kemble

Part 2. Excavation

4. Letters

5. Property

6. Daughters’ Work

7. Secrets

8. Lost

Part 3. Betrayals

9. Trouble

10. Revolt

11. Let Them Flow

12. New Order

Part 4. Inheritance

13. Industry

14. Matilda

15. Songs

16. Justice

Part 5. A Grandmother’s Nightmare

17. State v. Fricie Griffin

18. Mr. Scarlett

After

Notes on Sources

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

List of Abbreviations

Note on Language

Before

Part 1. Myth

1. Midnight

2. The Family Album

3. Fanny Kemble

Part 2. Excavation

4. Letters

5. Property

6. Daughters’ Work

7. Secrets

8. Lost

Part 3. Betrayals

9. Trouble

10. Revolt

11. Let Them Flow

12. New Order

Part 4. Inheritance

13. Industry

14. Matilda

15. Songs

16. Justice

Part 5. A Grandmother’s Nightmare

17. State v. Fricie Griffin

18. Mr. Scarlett

After

Notes on Sources

Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

“Scarlett is both a deeply intimate family history as well as a candid consideration of the history of slavery and racism in the United States. Perhaps more importantly, Scarlett demonstrates the ways that these two histories are inextricably bound for American families on all sides of the color line. Much in the tradition of Edward Ball’s Slaves in the Family, Scarlett faces a difficult history head-on, showing how slavery continues to reverberate in the lives of all Americans.”—Jason R. Young, author of Rituals of Resistance: African Atlantic Religion in Kongo and the Lowcountry South in the Era of Slavery

“Many of us who came of age in the bruising, suffocating silence of an enslaver family are awakening to how this silence cripples us all and deeply endangers our nation. . . . Leslie Stainton’s Scarlett awakens us as it issues its summons, both elegant and heartbreaking. While refusing to look away from her Georgia cotton-empire family’s many racist sins and their effects on the present, Stainton’s exquisite writing and personal transformation shines a sure and steady light for others who would, like her, answer those summonses that our long-stifled grandmothers issued to us in childhood.”—Karen Branan, author of The Family Tree: A Lynching in Georgia, a Legacy of Secrets, and My Search for the Truth

“Leslie Stainton ‘gets it.’ This modern-day Fanny Kemble didn’t marry into the slavocracy of coastal Georgia; she inherited its wealth, its mythology, and its ‘Scarlett’ letters. Her lyrical and rewarding book, rich in historical detail, recounts with candor a brave journey of self-discovery. Stainton’s deeply personal odyssey links present to past and dares other privileged Americans with troubling family roots to do the hard emotional and archival work of confronting their real ancestral story. This way lies healing, for self and society.”—Peter H. Wood, author of Black Majority: Race, Rice, and Rebellion in South Carolina, 1670–1740

“With history again being weaponized, it makes perfect timing for the release of Leslie Stainton’s vital story.”—Joseph McGill Jr., founder of the Slave Dwelling Project and coauthor, with Herb Frazer, of Sleeping with the Ancestors: How I Followed the Footprints of Slavery

“Beautiful, elegiac, and urgent, Scarlett resonates with tidal force. Leslie Stainton takes us on a search for the truth about her enslaving Georgia ancestors, the Scarletts, and through a reckoning with the myths and distortions of their painful history, from Gone with the Wind to today. In her family as in the American nation, the truth about slavery and segregation lay buried under denial, delusion, and pride. Pulling us all into its depths, this is a memoir that manages to be both bracingly honest and profoundly hopeful.”—William G. Thomas III, author of A Question Of Freedom: The Families Who Challenged Slavery from the Nation’s Founding to the Civil War

“This timely and powerful book . . . sheds important new light on the evils of historic slavery and its persistent and profound present-day impacts on all Americans. With searing detail, Leslie Stainton traces her ancestors’ complicity in the barbarous practices of buying, selling, hunting, and violating enslaved men, women, and children. Scarlett exemplifies the kind of candor and courage we so urgently need if we are ever to undo the cruelties and lies of racism and heal as a nation.”—Thomas Norman DeWolf, author of Inheriting the Trade and coauthor of Gather at the Table

“An unflinching look at one Southern family’s ties to slavery, Scarlett is a richly wrought portrait of how the complex legacy of enslavement echoes down to today. Leslie Stainton has given us a remarkable, brave, and beautifully written book.”—Scott Ellsworth, author of Midnight on the Potomac: The Last Year of the Civil War, the Lincoln Assassination, and the Rebirth of America

“Leslie Stainton’s beautifully written and heartfelt personal memoir about her own family’s history, so intertwined with American slavery, should be read by all those interested in the complicated nature of America’s racial past. As William Faulkner wrote, the past is neither dead nor truly past.”—Jonathan Daniel Wells, author of The Kidnapping Club: Wall Street, Slavery, and Resistance on the Eve of the Civil War

“Leslie Stainton is a talented storyteller, gradually revealing how this white Georgia family’s history is interwoven with stories of enslaving and what the lives of those enslaved persons were like.”—Phoebe Kilby, coauthor with Betty Kilby Baldwin of Cousins: Connected through Slavery, a Black Woman and a White Woman Discover Their Past—and Each Other

Descriere

From a sixth-generation descendant of the enslaving Scarletts of Georgia, this searing account of one family’s complicity in slavery and its violent aftermath unravels the lies of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind and shows how slavery’s legacy persists today.