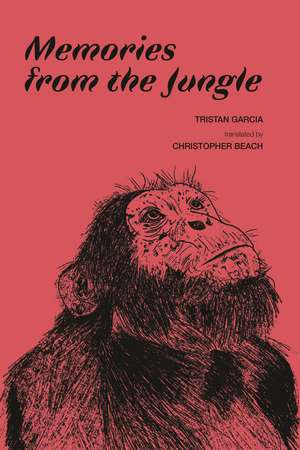

Memories from the Jungle

Autor Tristan Garcia Traducere de Christopher Beachen Limba Engleză Paperback – mai 2025

Doogie is no ordinary chimpanzee: gifted with an exceptional intelligence (perhaps the result of a scientific experiment), he has been taught a fairly sophisticated version of the human language, is capable of human emotions such as love and jealousy, and has a highly developed understanding of human behavior. After an accident to the spacecraft that was bringing him back to Earth from an orbital station, Doogie finds himself alone in the jungle. In order to survive, he must rediscover the very animal nature he has been trained to reject.

Preț: 129.56 lei

Puncte Express: 194

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.91€ • 26.54$ • 19.90£

22.91€ • 26.54$ • 19.90£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Livrare express 17-21 martie pentru 30.89 lei

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781496238535

ISBN-10: 1496238532

Pagini: 268

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1496238532

Pagini: 268

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Tristan Garcia is a rising star of the French intellectual and literary world, having published several books of philosophy—including the influential Form and Object—as well as eight works of fiction. His first novel won the Prix de Flore and was translated into English as Hate: A Romance. Garcia is on the philosophy faculty at the Jean Moulin University, Lyon 3. Christopher Beach is the co-translator of Annie Ernaux’s Do What They Say or Else (Nebraska, 2022). He is an independent scholar, editor, and translator.

Extras

A Human Being Speaks . . .

Sadly, it’s my nature. No matter what happens, I still think about myself and

others from the point of view of an ethologist.

That’s why I think I can understand my behavior, even though it’s why I

also know the degree to which that understanding seldom affects my behavior

and rarely changes it. But what this ape was for me, and what I was

for him, I can’t explain to myself. I was the last inheritor of a meandering

movement through which we, as humans, placed ourselves in opposition

to other animals, only to arrive at the paradoxical point where we realized

why and how we nonetheless belonged to them. It was only very belatedly

that it became permissible for us to understand ourselves as animals among

other animals, and to understand the animality within us. At the twilight of

our history, we discovered that we were also a species and that they were

also individuals, even if they did not always become persons. Animals . . .

We have detested them, and we have loved them; we have domesticated,

tortured, and caressed them; we have given them Latin names; we have

described and thoroughly explained their behavior, without any hope that

they would ever show us what we are, and without any hope that they would

one day forgive us. Too late, we grasped the differences that exist within a

single species, the correct or incorrect way of approaching each one of them,

the culture that a group of them could produce, and the singular genius of

a few among them.

And at times we felt, too strongly, the desire to make them evolve, the

desire to finally hear them speak to us. Because we are all alone, we big

talkers of Creation.

Who knows why we wanted to make them into our children.

In part, it was because in modeling them in our image we wished to

become the gods that we imagined they thought of as theirs. But it was

also because we dreamed that, by understanding them, we would be able

to rediscover to what degree and in what way we, like them, were animals.

We are something in between.

I suppose that in the past it was between God and animal, and today it

is between animal and machine . . . I think that in his own eyes the human

being is never anything other than something in between, and that he will

always remain in that situation.

Inhabited as I was by the floating consciousness—which had now come

to the surface—of our amphibious status of being plunged into the foul

water of what we are while breathing the gamey air of what we do, what was

it that motivated me to take care of this creature from a species other than

my own, as if I had the opportunity to hoist him up toward me? And as if

he had the same opportunity to pull me out from my mildewed humanity

to show me what we humans, seen from the outside, really are.

Was it a debt contracted at the point in our evolution when we had to

deny them, to oppose our nature to theirs? Will we, sooner or later, repay the

debt that exists only in the accounts that we keep, since it certainly doesn’t

exist in accounts kept between animals? How would we even do this? By

guiding them toward us? By going back toward them? By leaving them

without us so that they can be themselves? By giving them rights that they

will not take and to which they are indifferent? By assuming all obligations,

ours as well as theirs? I don’t know what animality will be for my children,

or for the children to come. Will it be a vague memory from a museum, or

will it once again be something alive?

I’m getting lost in all this.

The more I study and spend time with the animal, the less I think that I

know what it is, where it came from, and where it is going.

These are nothing more than confused notes jotted down on paper, on

the last page of my last notebook, before this little book goes back into the

old wooden chest in the museum where I keep my unfinished work, no

longer believing that it will ever interest my daughters or the children of my

daughters. Because it’s too late for that.

Now, like an image or a mirage, the animal is disappearing, and what he

is, what he was, I don’t think I know anymore. Everything is evaporating.

In my role as an ethologist, I have failed.

It seems to me that I will never again see my humanity from the exterior,

through the eyes of another, a chimpanzee. That is finished.

I still think about it today, but I no longer reflect on it.

It is only his baroque chimpanzee language, so close to ours and yet so

distant from it, a bit more or a bit less than human language, that regularly

comes back to me. It was a primitive or, who knows, perhaps a futuristic language.

It was conveyed through cries, through hand signs, and through the

tactile screen of the computer he had at the time. It was jumbled sentences,

with an idiomatic mix of his rudimentary language, enlivened by the pretentious

turns of phrase that he so often attempted and sometimes combined

with a makeshift pidgin. It was the unhoped-for fruit of fanatic learning.

Because we took him for a genius, the poor thing. It was the language of

an entirely other species, perhaps our last chance to hear strangeness in its

complete form. That is what I believed at the time. We are much too familiar

to ourselves. Look at how stiff, heavy, and conventional my own language is.

Forgive me, and take all of this as an experiment that a short while ago gave

meaning to the monochordal voice of our tired human existence, a voice

that had nothing new to offer my blasé ears. Perhaps this experiment, my

experiment, will in time also become yours. To perceive our words, almost

identical but in a mouth that is so different from the one that constantly

houses our ridiculous human chatter. I would so much like for his bric-a-brac

dialect to resonate once again between the bulging folds of my civilized,

polite, evolved, tired, and obsolete human brain.

And even if he is mute today, I can still hear and will always hear him grunt,

laugh, and reason. If I could enter his little head one last time, oh, if only . . .

Sadly, it’s my nature. No matter what happens, I still think about myself and

others from the point of view of an ethologist.

That’s why I think I can understand my behavior, even though it’s why I

also know the degree to which that understanding seldom affects my behavior

and rarely changes it. But what this ape was for me, and what I was

for him, I can’t explain to myself. I was the last inheritor of a meandering

movement through which we, as humans, placed ourselves in opposition

to other animals, only to arrive at the paradoxical point where we realized

why and how we nonetheless belonged to them. It was only very belatedly

that it became permissible for us to understand ourselves as animals among

other animals, and to understand the animality within us. At the twilight of

our history, we discovered that we were also a species and that they were

also individuals, even if they did not always become persons. Animals . . .

We have detested them, and we have loved them; we have domesticated,

tortured, and caressed them; we have given them Latin names; we have

described and thoroughly explained their behavior, without any hope that

they would ever show us what we are, and without any hope that they would

one day forgive us. Too late, we grasped the differences that exist within a

single species, the correct or incorrect way of approaching each one of them,

the culture that a group of them could produce, and the singular genius of

a few among them.

And at times we felt, too strongly, the desire to make them evolve, the

desire to finally hear them speak to us. Because we are all alone, we big

talkers of Creation.

Who knows why we wanted to make them into our children.

In part, it was because in modeling them in our image we wished to

become the gods that we imagined they thought of as theirs. But it was

also because we dreamed that, by understanding them, we would be able

to rediscover to what degree and in what way we, like them, were animals.

We are something in between.

I suppose that in the past it was between God and animal, and today it

is between animal and machine . . . I think that in his own eyes the human

being is never anything other than something in between, and that he will

always remain in that situation.

Inhabited as I was by the floating consciousness—which had now come

to the surface—of our amphibious status of being plunged into the foul

water of what we are while breathing the gamey air of what we do, what was

it that motivated me to take care of this creature from a species other than

my own, as if I had the opportunity to hoist him up toward me? And as if

he had the same opportunity to pull me out from my mildewed humanity

to show me what we humans, seen from the outside, really are.

Was it a debt contracted at the point in our evolution when we had to

deny them, to oppose our nature to theirs? Will we, sooner or later, repay the

debt that exists only in the accounts that we keep, since it certainly doesn’t

exist in accounts kept between animals? How would we even do this? By

guiding them toward us? By going back toward them? By leaving them

without us so that they can be themselves? By giving them rights that they

will not take and to which they are indifferent? By assuming all obligations,

ours as well as theirs? I don’t know what animality will be for my children,

or for the children to come. Will it be a vague memory from a museum, or

will it once again be something alive?

I’m getting lost in all this.

The more I study and spend time with the animal, the less I think that I

know what it is, where it came from, and where it is going.

These are nothing more than confused notes jotted down on paper, on

the last page of my last notebook, before this little book goes back into the

old wooden chest in the museum where I keep my unfinished work, no

longer believing that it will ever interest my daughters or the children of my

daughters. Because it’s too late for that.

Now, like an image or a mirage, the animal is disappearing, and what he

is, what he was, I don’t think I know anymore. Everything is evaporating.

In my role as an ethologist, I have failed.

It seems to me that I will never again see my humanity from the exterior,

through the eyes of another, a chimpanzee. That is finished.

I still think about it today, but I no longer reflect on it.

It is only his baroque chimpanzee language, so close to ours and yet so

distant from it, a bit more or a bit less than human language, that regularly

comes back to me. It was a primitive or, who knows, perhaps a futuristic language.

It was conveyed through cries, through hand signs, and through the

tactile screen of the computer he had at the time. It was jumbled sentences,

with an idiomatic mix of his rudimentary language, enlivened by the pretentious

turns of phrase that he so often attempted and sometimes combined

with a makeshift pidgin. It was the unhoped-for fruit of fanatic learning.

Because we took him for a genius, the poor thing. It was the language of

an entirely other species, perhaps our last chance to hear strangeness in its

complete form. That is what I believed at the time. We are much too familiar

to ourselves. Look at how stiff, heavy, and conventional my own language is.

Forgive me, and take all of this as an experiment that a short while ago gave

meaning to the monochordal voice of our tired human existence, a voice

that had nothing new to offer my blasé ears. Perhaps this experiment, my

experiment, will in time also become yours. To perceive our words, almost

identical but in a mouth that is so different from the one that constantly

houses our ridiculous human chatter. I would so much like for his bric-a-brac

dialect to resonate once again between the bulging folds of my civilized,

polite, evolved, tired, and obsolete human brain.

And even if he is mute today, I can still hear and will always hear him grunt,

laugh, and reason. If I could enter his little head one last time, oh, if only . . .

Recenzii

“Embedded within this whimsical wild ride to a speculative future is a send-up of B. F. Skinner’s theory of behaviorism. In Christopher Beach’s adept translation, Tristan Garcia’s language play brings across the sympathetic and humanlike chimpanzee Doogie and his quest for a middle ground between nature and nurture.”—Elizabeth Kadetsky, author of On the Island at the Center of the Center of the World

“Writing in a style that is both precise and colorful, Tristan Garcia pursues his argument without falling into pontificating jargon, renewing in a playful mode a problem that goes back to Aristotle. It is well known: man is an ape to man, and vice versa.”—Emilie Colombani, Technikart

“An intelligent, original, and bold novel . . . and, ultimately, a very moving one, about the foundations of civilization, language, knowledge, and animality.”—Baptiste Liger, L’Express

“A kind of Jungle Book, but in reverse. It’s the comic version of the world of men, as seen by the animals of tomorrow. It’s daring, it’s thoughtful, it’s incisive.”—Hubert Artus, Rolling Stone

Descriere

In French author Tristan Garcia’s Memories from the Jungle chimpanzee Doogie is marooned in the jungle after being raised by human beings. With his exceptional intelligence, Doogie must confront not only the dangers of the natural world but also his place in human and nonhuman society.