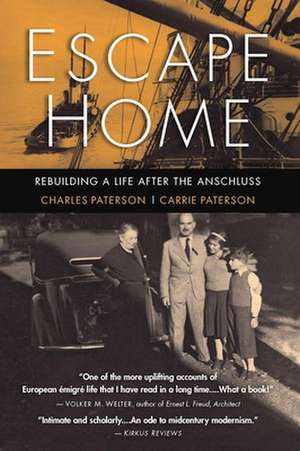

Escape Home

Autor Charles Paterson Editat de Carrie Paterson, Hensley Peterson, Paul Andersonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 21 mar 2017

“Intimate and scholarly... Patient readers will be rewarded. An encyclopedic and epistolary family history, a eulogy for pre-Reich Vienna and an ode to midcentury modernism.”

— Kirkus Reviews

“This jewel should not be called a book but a museum.”

— Will Semler, author (Melbourne, Australia)

"One of the more uplifting accounts of European émigré life that I have read in a long time.... It will touch you to tears right away, regardless of how many accounts of similar fates you believe to have studied and understood.... What a book!"

— Volker M. Welter, author and architectural historian

"An invaluable addition to the literature on the birth of modern Aspen."

—Stewart Oksenhorn, The Aspen Times

Charles Paterson (born Karl Schanzer) was only nine years old when the Nazis invaded Austria and his father, Stefan, fled with his children to avoid persecution. To assure their continued safety, the children were baptized and adopted by the Paterson family in Australia while Stefan made a harrowing escape through occupied France. It would be eight years, after much sorrow and loss, before Charles and his sister would reunite with Stefan in the United States.

After Charles and Stefan settle in Aspen, Colorado, amidst the snow-capped peaks that remind them of the Austrian Alps, Stefan becomes a high school teacher known for his humor and adventure stories while Charles teaches skiing, serves as a Frank Lloyd Wright apprentice, and then builds his thesis project, the The Boomerang ski lodge. Charles lives with Stefan at The Boomerang and, as Aspen grows into a world-class ski resort, spends fifty years welcoming thousands of people to the town with Austrian warmth and gemütlichkeit. Based on archival documents and letters, together with the authors’ personal reflections, Escape Home is a family memoir and a meditation on the domestic qualities of architecture, where the bonds of culture and family prove to be the true foundation for rebuilding meaningful lives and finding both security and freedom.

— Kirkus Reviews

“This jewel should not be called a book but a museum.”

— Will Semler, author (Melbourne, Australia)

"One of the more uplifting accounts of European émigré life that I have read in a long time.... It will touch you to tears right away, regardless of how many accounts of similar fates you believe to have studied and understood.... What a book!"

— Volker M. Welter, author and architectural historian

"An invaluable addition to the literature on the birth of modern Aspen."

—Stewart Oksenhorn, The Aspen Times

Charles Paterson (born Karl Schanzer) was only nine years old when the Nazis invaded Austria and his father, Stefan, fled with his children to avoid persecution. To assure their continued safety, the children were baptized and adopted by the Paterson family in Australia while Stefan made a harrowing escape through occupied France. It would be eight years, after much sorrow and loss, before Charles and his sister would reunite with Stefan in the United States.

After Charles and Stefan settle in Aspen, Colorado, amidst the snow-capped peaks that remind them of the Austrian Alps, Stefan becomes a high school teacher known for his humor and adventure stories while Charles teaches skiing, serves as a Frank Lloyd Wright apprentice, and then builds his thesis project, the The Boomerang ski lodge. Charles lives with Stefan at The Boomerang and, as Aspen grows into a world-class ski resort, spends fifty years welcoming thousands of people to the town with Austrian warmth and gemütlichkeit. Based on archival documents and letters, together with the authors’ personal reflections, Escape Home is a family memoir and a meditation on the domestic qualities of architecture, where the bonds of culture and family prove to be the true foundation for rebuilding meaningful lives and finding both security and freedom.

Preț: 123.27 lei

Puncte Express: 185

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.80€ • 25.25$ • 18.93£

21.80€ • 25.25$ • 18.93£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780997003468

ISBN-10: 0997003464

Pagini: 570

Ilustrații: Two-color art; 200 B&W photographs, maps, tables

Dimensiuni: 151 x 228 x 45 mm

Greutate: 0.87 kg

Editura: DoppelHouse Press

ISBN-10: 0997003464

Pagini: 570

Ilustrații: Two-color art; 200 B&W photographs, maps, tables

Dimensiuni: 151 x 228 x 45 mm

Greutate: 0.87 kg

Editura: DoppelHouse Press

Cuprins

Prologue XI

Introduction XIII

Part One

Chapter 1 Foundations 1

Chapter 2 The Werkbundsiedlung 1932-1938 15

Chapter 3 Weaving 24

Chapter 4 Childhood 31

Chapter 5 Mutti 50

Chapter 6 A Boy of Ten Is Already Grown 56

Chapter 7 My Dear Children 76

Chapter 8 Prisoners Don’t Ride Bicycles 83

Chapter 9 Sauf Conduit 93

Chapter 10 Australia 105

Chapter 11 War Cry 116

Chapter 12 Resurfacing 128

Chapter 13 The Goldens 136

Chapter 14 When War Is Over 144

Chapter 15 To America 154

Part Two

Chapter 16 Finding Home 164

Chapter 17 Summer of ‘49 178

Chapter 18 Manna from Heaven 191

Chapter 19 Dispossession 201

Chapter 20 What Traces Are Left 213

Chapter 21 Stefan and Max 1939–1947 227

Chapter 22 Aspen, Early 1950’s 239

Chapter 23 Prisoner of Fortune, Prisoner of War 250

Chapter 24 At the End of Empire 264

Chapter 25 Money Matters 276

Chapter 26 Basic Training 288

Chapter 27 The Tachinierer 299

Part Three

Chapter 28 Breaking Ground 312

Chapter 29 Taliesin 321

Chapter 30 A Critical Mix 336

Chapter 31 A Sympathetic Chord 349

Chapter 32 Architecture in Evolution 366

Chapter 33 Building 383

Chapter 34 Pencil to Paper 398

Chapter 35 Silversmithing 414

Chapter 36 Still Escaping 428

Chapter 37 Adaptations 438

Chapter 38 A Philosophy of Life 445

Chapter 39 A Cabin Is A Castle 455

Appendix I Recipes 459

Appendix II Map of Escape from Nazi-Occupied France 467

Appendix III Family Trees 473

Endnotes 481

Selected Bibliography 517

Acknowledgments 526

Index 533

Introduction XIII

Part One

Chapter 1 Foundations 1

Chapter 2 The Werkbundsiedlung 1932-1938 15

Chapter 3 Weaving 24

Chapter 4 Childhood 31

Chapter 5 Mutti 50

Chapter 6 A Boy of Ten Is Already Grown 56

Chapter 7 My Dear Children 76

Chapter 8 Prisoners Don’t Ride Bicycles 83

Chapter 9 Sauf Conduit 93

Chapter 10 Australia 105

Chapter 11 War Cry 116

Chapter 12 Resurfacing 128

Chapter 13 The Goldens 136

Chapter 14 When War Is Over 144

Chapter 15 To America 154

Part Two

Chapter 16 Finding Home 164

Chapter 17 Summer of ‘49 178

Chapter 18 Manna from Heaven 191

Chapter 19 Dispossession 201

Chapter 20 What Traces Are Left 213

Chapter 21 Stefan and Max 1939–1947 227

Chapter 22 Aspen, Early 1950’s 239

Chapter 23 Prisoner of Fortune, Prisoner of War 250

Chapter 24 At the End of Empire 264

Chapter 25 Money Matters 276

Chapter 26 Basic Training 288

Chapter 27 The Tachinierer 299

Part Three

Chapter 28 Breaking Ground 312

Chapter 29 Taliesin 321

Chapter 30 A Critical Mix 336

Chapter 31 A Sympathetic Chord 349

Chapter 32 Architecture in Evolution 366

Chapter 33 Building 383

Chapter 34 Pencil to Paper 398

Chapter 35 Silversmithing 414

Chapter 36 Still Escaping 428

Chapter 37 Adaptations 438

Chapter 38 A Philosophy of Life 445

Chapter 39 A Cabin Is A Castle 455

Appendix I Recipes 459

Appendix II Map of Escape from Nazi-Occupied France 467

Appendix III Family Trees 473

Endnotes 481

Selected Bibliography 517

Acknowledgments 526

Index 533

Recenzii

“Intimate and scholarly... Patient readers will be rewarded. An encyclopedic and epistolary family history, a eulogy for pre-Reich Vienna and an ode to midcentury modernism.”

— Kirkus Reviews

“This jewel should not be called a book but a museum.”

— Will Semler, author (Melbourne, Australia)

"One of the more uplifting accounts of European émigré life that I have read in a long time.... It will touch you to tears right away, regardless of how many accounts of similar fates you believe to have studied and understood.... What a book!"

— Volker M. Welter, author and architectural historian

"An invaluable addition to the literature on the birth of modern Aspen."

—Stewart Oksenhorn, The Aspen Times

Notă biografică

Charles Paterson: Charles Paterson was born Karl Schanzer in Vienna, Austria in 1929 and now lives in Aspen, Colorado. As a Jewish child he and his sister were adopted by the Australian Paterson family. An architectural designer, Paterson was one of the last apprentices to train under Frank Lloyd Wright.

Carrie Paterson: Carrie Paterson is an artist and writer based in Los Angeles. She writes for contemporary art journals, lectures at Southern California universities and is Publisher and Editor in chief at DoppelHouse Press.

Hensley Peterson is an editor based in Aspen, Colorado.

Paul Anderson: Paul Anderson is a writer of books and essays. He is a columnist for The Aspen Times.

Carrie Paterson: Carrie Paterson is an artist and writer based in Los Angeles. She writes for contemporary art journals, lectures at Southern California universities and is Publisher and Editor in chief at DoppelHouse Press.

Hensley Peterson is an editor based in Aspen, Colorado.

Paul Anderson: Paul Anderson is a writer of books and essays. He is a columnist for The Aspen Times.

Extras

Prologue

by Carrie Paterson

In 2005, my father Charles Paterson sold The Boomerang, a ski lodge

in Aspen, Colorado that he began as a small log cabin, built into a

thirty-five unit hotel, and continually managed since he was in his mid-twenties.

Upon retirement from over fifty years in business, he began

writing a memoir on index cards, episodes he had previously recounted

for me in 2002 in a series of video interviews he titled “Short Memories

of a Long Life.” Our friend Hensley Peterson, after hearing one of his

tales around a campfire, encouraged him to expand his memoir

into a book. She also began asking questions that led us to look

more deeply into the history surrounding his life’s events.

And so it began. He started to go through old trunks, drawers, and

collections of photographs, commencing to catalog his life. One day I

found he had laid out all his hats in an arc by the piano. His efforts were

accompanied by the clarity of my mother Fonda’s bright memories and

research. Over their forty-four years of marriage she has kept her own

files filled with articles and references that give context to his stories and

those of his father, Steve Schanzer, survivor of two world wars.

Steve, my grandfather, was a legendary storyteller who inspired

great affection and was an inspiration to many. When he emigrated to

the United States in 1941, he changed the family name from Schanzer to

Shanzer. He said he wanted to drop the “c” in order to “get the German

out,” as if he could banish from sight all the sorrows in his life that had

been brought about by the Anschluss, Hitler’s annexation in 1938 of our

family’s homeland, Austria.

My father Charles and my grandfather Steve are the central characters

of this book. However, excerpts from the letters of other key figures

help to fill its pages, including those from my father’s sister, my aunt

Doris Schneider, and a few rare memories from my grandmother Eva

Beck Schanzer, who died in 1938.

Midway through writing this book, amongst my grandfather’s

records, we found one dusty red file that had remained unopened for

many years. My father knew the tattered folder contained all the correspondence

between my grandfather and members of our family who

died in Europe during World War II —my great-aunt Claire Beck Loos

and my two great-grandmothers, Olga Feigl Beck and Rosa Schanzer—

but he had never looked closely through it. My mother wanted to read

the letters. My father protested. Despite my father’s misgivings, my

mother arranged for them to be scanned and translated. The letters

were written in my father’s native tongue, German, which he no longer

speaks. Many were difficult to decipher because they were penned in

Kurrentschrift, an old script based on German cursive writing from the

late medieval period. My grandfather had kept them laid neatly together

in chronological order, like a book he had not written but was responsible

for delivering.

With so many contributors to Escape Home, this book has become

a chorus. The principal voices are a father and son separated by war

and reunited, who shared a great love and were lucky to have each other.

Some details of these stories have been challenging to write, and others

to make sense of because even language can hide what has been buried

or unspoken over the course of time.

Introduction

by Charles Paterson

At the time of the German annexation of Austria, the Anschluss, I

was nine years old. Our family lived in Vienna’s thirteenth district.

As I learn about that year and the violent manner in which the country

was transformed almost overnight, I have changed the way I think about

my childhood. I have no memory of the day the Nazis marched onto the

Ringstrasse, but it altered my family’s life forever. We were thrown to

the winds. My father Steve, my uncle Max Beck, my sister Doris, and I

survived to tell this story.

In this book, we must all turn a page on tragedy, nevertheless, and

recognize that vision, intuition, and hope are guides for people in the

most terrible circumstances. I am writing our story to give insight to

what happened to people like us after our dispossession and to tell how

somehow, against all odds, we persevered and even thrived. I believe that

young people today, who see other times and their own difficulties, can

learn from our challenges, as I did from my father, that it takes courage

and tenacity to carry on, while you bring history with you.

When I was born in Vienna in 1929, I was named Karl Schanzer

after my grandfather. I am the eighth generation in my family of Viennese.

Through many twists of fate and the dramatic world influences

that caused them, I became Charles Paterson, a Viennese-Australian-

American. For the last ten years I have been rediscovering my past. As

I recover memories and letters, I have gained a new perspective on the

history I have known, and my life is changing yet again.

Since 1980, I have kept my father’s papers and many of his personal

effects in an old, wooden filing cabinet in the basement of our house in

Aspen, Colorado I designed and built in 1977 for my family. I had rarely

opened it since my father’s death in 1979.

At the onset of a winter soon after my retirement, I went rummaging

through the cabinet. The memorabilia brought back an intense feeling of

loss as I began looking through the boxes and files that tell of my father’s

life experiences first-hand. Old maps of trips spilled forth, photographs,

and my father’s Masonic vestments. One drawer contained his

favorite grey felt hat and a pair of antique Turkish wooden clogs said to

strengthen the feet. In another was a box of keys. I also found my Ski

Association pins—I was number thirty-one of the first Rocky Mountain

ski instructors to be certified—and mimeographed sheets of my father’s

self-crafted “gourmet” Austrian recipes. Another surprise was the red

silk necktie from the early 1930’s of a famous Czechoslovak-Viennese

architect, Adolf Loos, the husband of my aunt Claire Beck Loos.

Then I found a treasure trove of letters in a stack of old, well-kept

file folders. Like puzzle pieces, these letters, many written in German

and French, have provided the key to remembrances of a lost time that

remain with me still and bring this memoir alive. To my amazement, in

addition to these letters, my father also kept all the correspondence I had

ever sent to him from my first days in Aspen, Colorado starting in 1949,

and from Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, where I studied architecture

under Frank Lloyd Wright in the late 1950’s. He also diligently kept

copies of all his replies.

The adventures we told each other through the years lay before me

undiluted and unedited by memory. I had never thought of that room

as an archive for our lives and our relationship. Yet I have been living

with it right near my drafting room and my busy life all this time. The

discovery gave me great motivation.

Later my daughter and coauthor Carrie and one of our editors,

Hensley Peterson, delved a little deeper into the files. In what looked to

be a stack of old newspaper clippings, Carrie found my father’s journal

from 1914-1920 when he was made a prisoner in Siberia during the First

World War. Hensley made the important discovery of all the letters sent

by my sister and me from Australia to my father in New York when we

were separated for over eight years. My wife Fonda had always speculated

that since my father kept everything, the letters must be buried,

somewhere. That amazing day, we retrieved my entire teenage years.

Other exchanges with my father emerged, from and to our foster family,

and to advisors who enlightened my father, and now me as well, seventy

years later, about the life and trials of children who escaped Europe

during World War II .

Our stories are part of a larger history. One and a half million children

and teenagers perished in that Holocaust, but thankfully tens of

thousands were like us, sent away and rescued. Collectively we are the

last remaining witnesses of those tribulations. This book is an expression

of my gratitude and, by proxy, my father’s, to those who looked out

for us and saved our lives.

Chapter 1

Foundations [excerpt]

My father Stefan Schanzer was born in Vienna in 1889—as he used

to say, the same year as Adolf Hitler—in the last generation of

the Habsburg Empire. Vienna, a great mixing ground for ethnicities,

religions, and nationalities, was at that time one of the most culturally

diverse places in the world. As a destitute artist Hitler lived a miserable

life there for five years starting in 1908, and from that experience he

formed his political opinions that would change the face and destiny

of Europe. But my father never could nor would have blamed Vienna

for what transpired in our lives. People, yes, but not the city. It was

a singularly special place in his memories, the central jewel in all his

stories, and the heart of his identity.

Among my father’s collection of items he felt were important to

take with us when we abandoned the city after the Nazi occupation,

the 1936 phone book demonstrates this fact. An imposing volume with

“Habsburg” in white lettering on its red spine, it is testament to the

smallness of that area of Europe and to its nostalgia, almost part of

the grammar of a city with such historic culture and splendor. After

World War II , when my father would meet people from Vienna, he

would look them up—much could still be told about someone living in

the new world if they used to call his great city home. With such a book

published before tragedies and disasters, Vienna—for him a lost love—

could be frozen in time.

A point of pride for my father was that our relatives were among a

small number of Jewish families, a few hundred people, granted special

permission by the Habsburg Monarchy to live in the city during the

eighteenth century. We trace our ancestry back through one of the

oldest recorded families, the Sinzheims. My third great-grandfather,

Abraham Löwy, who married Regina Sinzheim, was born in Vienna

circa 1749 and went by the name of Goldstein, as he was a jeweler.

This profession would have uniquely enabled him and his large family

to live year-round in Vienna because jewelers were court-appointed to

evaluate the worth of items being presented as collateral by citizens

who sought loans from the Emperor. This job provided an avenue for

a kind of assimilation, possible in the Empire but eventually exposed

as a lie only decades after the fabric of the monarchy unraveled in the

First World War. When power shifted again in the mid-1930’s, people

like us, who never considered we could be vulnerable to such charges,

were labeled “outsiders.”

Even before then, my father’s family must have felt our origins

were our vulnerability. He never actually mentioned that our direct

Schanzer line originated along the western border of Galicia, now

Poland. Immigrants from that area came to Vienna in waves, along with

the Ostjuden—many desperately poor—who were looking for work and

fleeing pogroms in the Russian Pale. The Schanzers, I was told by my

father, were frequent guarantors for Galician immigrants to Vienna.

That Galicians could have been relatives was unknown to me. But in

2011 we found that in Galicia, hundreds of Schanzers populate the birth

and death records from the turn of the last century.

When our family recently discovered a gravestone in the Vienna

Central Cemetery we learned that my great-grandfather, Bernhard

Baruch Schanzer, was born in Lipnik, Galicia in 1833. I like to entertain

the thought that our family could have also been skiers from that picturesque

region of the Carpathian Mountains; other Schanzers related to us

are from the nearby ski town of Zywiec. My father may not have known—

he never mentioned it—but I think he would have enjoyed the coincidence;

skiing has been a favorite pastime for generations in our family.

A Schanz is a “ski jump,” oddly enough.

Bernhard’s birthplace of Lipnik was famous for its textiles and dye

works in the nineteenth century. Connected by railway to Krakow and

Vienna, it became a major center for the trade. Bernhard started a shipping

company, Schanzer Forwarding Co., which he later sold to Schenker

& Co., now DB Schenker, still one of the largest in the world. This was

an irony for my father, as he liked to point out—a shipping company, and

there we were, having been sent by boat, on trains, and under the cover

of night in cars, like packages, to fates around the globe.

....

by Carrie Paterson

In 2005, my father Charles Paterson sold The Boomerang, a ski lodge

in Aspen, Colorado that he began as a small log cabin, built into a

thirty-five unit hotel, and continually managed since he was in his mid-twenties.

Upon retirement from over fifty years in business, he began

writing a memoir on index cards, episodes he had previously recounted

for me in 2002 in a series of video interviews he titled “Short Memories

of a Long Life.” Our friend Hensley Peterson, after hearing one of his

tales around a campfire, encouraged him to expand his memoir

into a book. She also began asking questions that led us to look

more deeply into the history surrounding his life’s events.

And so it began. He started to go through old trunks, drawers, and

collections of photographs, commencing to catalog his life. One day I

found he had laid out all his hats in an arc by the piano. His efforts were

accompanied by the clarity of my mother Fonda’s bright memories and

research. Over their forty-four years of marriage she has kept her own

files filled with articles and references that give context to his stories and

those of his father, Steve Schanzer, survivor of two world wars.

Steve, my grandfather, was a legendary storyteller who inspired

great affection and was an inspiration to many. When he emigrated to

the United States in 1941, he changed the family name from Schanzer to

Shanzer. He said he wanted to drop the “c” in order to “get the German

out,” as if he could banish from sight all the sorrows in his life that had

been brought about by the Anschluss, Hitler’s annexation in 1938 of our

family’s homeland, Austria.

My father Charles and my grandfather Steve are the central characters

of this book. However, excerpts from the letters of other key figures

help to fill its pages, including those from my father’s sister, my aunt

Doris Schneider, and a few rare memories from my grandmother Eva

Beck Schanzer, who died in 1938.

Midway through writing this book, amongst my grandfather’s

records, we found one dusty red file that had remained unopened for

many years. My father knew the tattered folder contained all the correspondence

between my grandfather and members of our family who

died in Europe during World War II —my great-aunt Claire Beck Loos

and my two great-grandmothers, Olga Feigl Beck and Rosa Schanzer—

but he had never looked closely through it. My mother wanted to read

the letters. My father protested. Despite my father’s misgivings, my

mother arranged for them to be scanned and translated. The letters

were written in my father’s native tongue, German, which he no longer

speaks. Many were difficult to decipher because they were penned in

Kurrentschrift, an old script based on German cursive writing from the

late medieval period. My grandfather had kept them laid neatly together

in chronological order, like a book he had not written but was responsible

for delivering.

With so many contributors to Escape Home, this book has become

a chorus. The principal voices are a father and son separated by war

and reunited, who shared a great love and were lucky to have each other.

Some details of these stories have been challenging to write, and others

to make sense of because even language can hide what has been buried

or unspoken over the course of time.

Introduction

by Charles Paterson

At the time of the German annexation of Austria, the Anschluss, I

was nine years old. Our family lived in Vienna’s thirteenth district.

As I learn about that year and the violent manner in which the country

was transformed almost overnight, I have changed the way I think about

my childhood. I have no memory of the day the Nazis marched onto the

Ringstrasse, but it altered my family’s life forever. We were thrown to

the winds. My father Steve, my uncle Max Beck, my sister Doris, and I

survived to tell this story.

In this book, we must all turn a page on tragedy, nevertheless, and

recognize that vision, intuition, and hope are guides for people in the

most terrible circumstances. I am writing our story to give insight to

what happened to people like us after our dispossession and to tell how

somehow, against all odds, we persevered and even thrived. I believe that

young people today, who see other times and their own difficulties, can

learn from our challenges, as I did from my father, that it takes courage

and tenacity to carry on, while you bring history with you.

When I was born in Vienna in 1929, I was named Karl Schanzer

after my grandfather. I am the eighth generation in my family of Viennese.

Through many twists of fate and the dramatic world influences

that caused them, I became Charles Paterson, a Viennese-Australian-

American. For the last ten years I have been rediscovering my past. As

I recover memories and letters, I have gained a new perspective on the

history I have known, and my life is changing yet again.

Since 1980, I have kept my father’s papers and many of his personal

effects in an old, wooden filing cabinet in the basement of our house in

Aspen, Colorado I designed and built in 1977 for my family. I had rarely

opened it since my father’s death in 1979.

At the onset of a winter soon after my retirement, I went rummaging

through the cabinet. The memorabilia brought back an intense feeling of

loss as I began looking through the boxes and files that tell of my father’s

life experiences first-hand. Old maps of trips spilled forth, photographs,

and my father’s Masonic vestments. One drawer contained his

favorite grey felt hat and a pair of antique Turkish wooden clogs said to

strengthen the feet. In another was a box of keys. I also found my Ski

Association pins—I was number thirty-one of the first Rocky Mountain

ski instructors to be certified—and mimeographed sheets of my father’s

self-crafted “gourmet” Austrian recipes. Another surprise was the red

silk necktie from the early 1930’s of a famous Czechoslovak-Viennese

architect, Adolf Loos, the husband of my aunt Claire Beck Loos.

Then I found a treasure trove of letters in a stack of old, well-kept

file folders. Like puzzle pieces, these letters, many written in German

and French, have provided the key to remembrances of a lost time that

remain with me still and bring this memoir alive. To my amazement, in

addition to these letters, my father also kept all the correspondence I had

ever sent to him from my first days in Aspen, Colorado starting in 1949,

and from Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, where I studied architecture

under Frank Lloyd Wright in the late 1950’s. He also diligently kept

copies of all his replies.

The adventures we told each other through the years lay before me

undiluted and unedited by memory. I had never thought of that room

as an archive for our lives and our relationship. Yet I have been living

with it right near my drafting room and my busy life all this time. The

discovery gave me great motivation.

Later my daughter and coauthor Carrie and one of our editors,

Hensley Peterson, delved a little deeper into the files. In what looked to

be a stack of old newspaper clippings, Carrie found my father’s journal

from 1914-1920 when he was made a prisoner in Siberia during the First

World War. Hensley made the important discovery of all the letters sent

by my sister and me from Australia to my father in New York when we

were separated for over eight years. My wife Fonda had always speculated

that since my father kept everything, the letters must be buried,

somewhere. That amazing day, we retrieved my entire teenage years.

Other exchanges with my father emerged, from and to our foster family,

and to advisors who enlightened my father, and now me as well, seventy

years later, about the life and trials of children who escaped Europe

during World War II .

Our stories are part of a larger history. One and a half million children

and teenagers perished in that Holocaust, but thankfully tens of

thousands were like us, sent away and rescued. Collectively we are the

last remaining witnesses of those tribulations. This book is an expression

of my gratitude and, by proxy, my father’s, to those who looked out

for us and saved our lives.

Chapter 1

Foundations [excerpt]

My father Stefan Schanzer was born in Vienna in 1889—as he used

to say, the same year as Adolf Hitler—in the last generation of

the Habsburg Empire. Vienna, a great mixing ground for ethnicities,

religions, and nationalities, was at that time one of the most culturally

diverse places in the world. As a destitute artist Hitler lived a miserable

life there for five years starting in 1908, and from that experience he

formed his political opinions that would change the face and destiny

of Europe. But my father never could nor would have blamed Vienna

for what transpired in our lives. People, yes, but not the city. It was

a singularly special place in his memories, the central jewel in all his

stories, and the heart of his identity.

Among my father’s collection of items he felt were important to

take with us when we abandoned the city after the Nazi occupation,

the 1936 phone book demonstrates this fact. An imposing volume with

“Habsburg” in white lettering on its red spine, it is testament to the

smallness of that area of Europe and to its nostalgia, almost part of

the grammar of a city with such historic culture and splendor. After

World War II , when my father would meet people from Vienna, he

would look them up—much could still be told about someone living in

the new world if they used to call his great city home. With such a book

published before tragedies and disasters, Vienna—for him a lost love—

could be frozen in time.

A point of pride for my father was that our relatives were among a

small number of Jewish families, a few hundred people, granted special

permission by the Habsburg Monarchy to live in the city during the

eighteenth century. We trace our ancestry back through one of the

oldest recorded families, the Sinzheims. My third great-grandfather,

Abraham Löwy, who married Regina Sinzheim, was born in Vienna

circa 1749 and went by the name of Goldstein, as he was a jeweler.

This profession would have uniquely enabled him and his large family

to live year-round in Vienna because jewelers were court-appointed to

evaluate the worth of items being presented as collateral by citizens

who sought loans from the Emperor. This job provided an avenue for

a kind of assimilation, possible in the Empire but eventually exposed

as a lie only decades after the fabric of the monarchy unraveled in the

First World War. When power shifted again in the mid-1930’s, people

like us, who never considered we could be vulnerable to such charges,

were labeled “outsiders.”

Even before then, my father’s family must have felt our origins

were our vulnerability. He never actually mentioned that our direct

Schanzer line originated along the western border of Galicia, now

Poland. Immigrants from that area came to Vienna in waves, along with

the Ostjuden—many desperately poor—who were looking for work and

fleeing pogroms in the Russian Pale. The Schanzers, I was told by my

father, were frequent guarantors for Galician immigrants to Vienna.

That Galicians could have been relatives was unknown to me. But in

2011 we found that in Galicia, hundreds of Schanzers populate the birth

and death records from the turn of the last century.

When our family recently discovered a gravestone in the Vienna

Central Cemetery we learned that my great-grandfather, Bernhard

Baruch Schanzer, was born in Lipnik, Galicia in 1833. I like to entertain

the thought that our family could have also been skiers from that picturesque

region of the Carpathian Mountains; other Schanzers related to us

are from the nearby ski town of Zywiec. My father may not have known—

he never mentioned it—but I think he would have enjoyed the coincidence;

skiing has been a favorite pastime for generations in our family.

A Schanz is a “ski jump,” oddly enough.

Bernhard’s birthplace of Lipnik was famous for its textiles and dye

works in the nineteenth century. Connected by railway to Krakow and

Vienna, it became a major center for the trade. Bernhard started a shipping

company, Schanzer Forwarding Co., which he later sold to Schenker

& Co., now DB Schenker, still one of the largest in the world. This was

an irony for my father, as he liked to point out—a shipping company, and

there we were, having been sent by boat, on trains, and under the cover

of night in cars, like packages, to fates around the globe.

....

Textul de pe ultima copertă

"A compelling story of one family's escape from Austria and Czechoslovakia at the beginning of World War II. With grace and courage, Charles Paterson, his father Steve, and his sister Doris, coped with the hardship that transformed their lives."

—William J. Cabaniss

United States Ambassador to the Czech Republic, 2004-2006

"This historical memoir is an engrossing saga, profusely illustrated and fully documented, the stuff that makes an intriguing feature film. I heartedly endorse it."

—Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer

Former Director of The Frank Lloyd Wright Archives

March 12, 1938—The Anschluss. Hitler annexes Austria into the Third Reich. For Karl Schanzer, a nine-year-old Viennese boy of Jewish heritage, life is irrevocably altered.

Fleeing Austria and then Czechoslovakia as the countries fall to the Nazis, and then France only steps ahead of the German invasion, a father makes the heart-rending decision to send his children to safety under the guise of adoption by the Paterson family in Australia. There, Karl becomes Charles Paterson and with his new name reinvents his identity in a foreign land. Based on memories of events as well as newly uncovered documents and accounts found in letters between family members, Escape Home is a riveting story of discovery and coming to terms with a past that casts a long shadow.

Refugees and immigrants, the small surviving Schanzer-Paterson family who reunite in the United States only after many years, together tell a story that reaches beyond specific events. Escape Home also speaks to concerns of our present times, where war, economic hardship, and disaster make forced migration increasingly common.

The emergence of modern architecture plays an important role in this story, from pre-war innovations in Central Europe that were part of the family’s heritage and surroundings, to the late 1950’s, when as a young man Paterson came to formulate his own philosophy of life and design as an apprentice under Frank Lloyd Wright.

Escape Home is at once an engaging tale of a young refugee from Hitler’s Europe making a new and fascinating life for himself in post-war America and a reverential homage to his Viennese father’s survival after living through not one, but two, world wars. This is a memoir of family love, personal adventure, and discovery as both father and son put the tragedy of their European past behind them to build a fresh and promising future in their new world of America."

—Loren Jenkins

Pulitzer Prize winning foreign correspondent

Escape Home is a hope-filled meditation on the way people adapt the past to present conditions, learn to see the world with clarity even through tribulations, use humor as a tool for stability, and integrate their heritage into utterly new circumstances.

—William J. Cabaniss

United States Ambassador to the Czech Republic, 2004-2006

"This historical memoir is an engrossing saga, profusely illustrated and fully documented, the stuff that makes an intriguing feature film. I heartedly endorse it."

—Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer

Former Director of The Frank Lloyd Wright Archives

March 12, 1938—The Anschluss. Hitler annexes Austria into the Third Reich. For Karl Schanzer, a nine-year-old Viennese boy of Jewish heritage, life is irrevocably altered.

Fleeing Austria and then Czechoslovakia as the countries fall to the Nazis, and then France only steps ahead of the German invasion, a father makes the heart-rending decision to send his children to safety under the guise of adoption by the Paterson family in Australia. There, Karl becomes Charles Paterson and with his new name reinvents his identity in a foreign land. Based on memories of events as well as newly uncovered documents and accounts found in letters between family members, Escape Home is a riveting story of discovery and coming to terms with a past that casts a long shadow.

Refugees and immigrants, the small surviving Schanzer-Paterson family who reunite in the United States only after many years, together tell a story that reaches beyond specific events. Escape Home also speaks to concerns of our present times, where war, economic hardship, and disaster make forced migration increasingly common.

The emergence of modern architecture plays an important role in this story, from pre-war innovations in Central Europe that were part of the family’s heritage and surroundings, to the late 1950’s, when as a young man Paterson came to formulate his own philosophy of life and design as an apprentice under Frank Lloyd Wright.

Escape Home is at once an engaging tale of a young refugee from Hitler’s Europe making a new and fascinating life for himself in post-war America and a reverential homage to his Viennese father’s survival after living through not one, but two, world wars. This is a memoir of family love, personal adventure, and discovery as both father and son put the tragedy of their European past behind them to build a fresh and promising future in their new world of America."

—Loren Jenkins

Pulitzer Prize winning foreign correspondent

Escape Home is a hope-filled meditation on the way people adapt the past to present conditions, learn to see the world with clarity even through tribulations, use humor as a tool for stability, and integrate their heritage into utterly new circumstances.

Descriere

The riveting family memoir of a Frank Lloyd Wright apprentice begins in Nazi-occupied Europe and journeys "home" to American modernism.