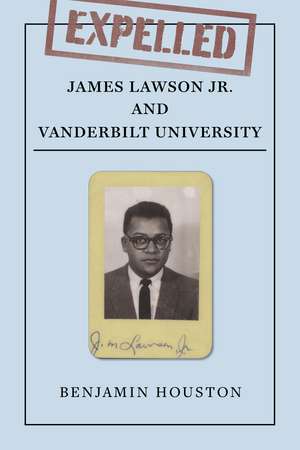

Expelled: James Lawson Jr. and Vanderbilt University

Autor Benjamin Houstonen Limba Engleză Hardback – 15 feb 2026

As demonstrations continued in Nashville and successive sit-ins saw violence erupt downtown, local Black ministers demanded an audience with Mayor Ben West. At this meeting, an exchange occurred that was misconstrued by subsequent newspaper reportage. Shortly thereafter, Lawson was summarily expelled from Vanderbilt, one semester shy of graduating.

Lawson’s ouster triggered a wave of repercussions and headlines. After extended negotiations with their superiors were rebuffed, a large contingent of Divinity School faculty resigned en masse. Simmering dissension between the university’s professors, Board of Trust, and administrators kept the crisis ongoing. Sustained criticism of Vanderbilt both within the city and nationally made for a turbulent situation as Lawson’s expulsion came to symbolize profound tensions about civil rights and racial justice.

Preț: 112.17 lei

Precomandă

Puncte Express: 168

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.85€ • 23.15$ • 17.20£

19.85€ • 23.15$ • 17.20£

Carte nepublicată încă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780826500120

ISBN-10: 0826500129

Pagini: 120

Ilustrații: 7 b&w images

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 mm

Editura: Vanderbilt University Press

Colecția Vanderbilt University Press

ISBN-10: 0826500129

Pagini: 120

Ilustrații: 7 b&w images

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 mm

Editura: Vanderbilt University Press

Colecția Vanderbilt University Press

Notă biografică

Benjamin Houston is a senior lecturer in the School of History, Classics, and Archaeology at Newcastle University in the United Kingdom. His specializations include twentieth-century US history, the Black freedom struggle, and oral history. He is the author of The Nashville Way: Racial Etiquette and the Struggle for Social Justice in a Southern City.

Extras

From the Introduction

That journey brought [James Lawson] to Nashville. It is not hackneyed to understand his time there as an instance where one man shaped a particular historical moment profoundly. Lawson played an “incomparable” role in shaping Nashville’s singular place in civil rights history. He moved there already well-established as an activist, deeply interlinked with networks of people trying to instill nonviolence more widely in Black communities across America. In doing that same work in Nashville, he cultivated a small cadre of ministers and students from the city’s Black churches and universities. Under Lawson’s tutelage, these regular people decided to do something extraordinary. They consciously chose to embrace bodily harm so as to literally step and sit outside the normal patterns of racism that intruded upon their lives.

Helped by Lawson’s preparatory work, these students were ready to act in 1960 when sit-ins shook the South in protest against the prevailing lunch-counter discrimination common to the era. Nashville’s demonstrations were distinguished for exhibiting on a substantial scale an unusually disciplined and sophisticated form of nonviolent resistance. This sustained commitment eventually made Nashville the first major Southern city to desegregate its lunch counters. Equally importantly, many of those forged with nonviolent steel by Lawson during the Nashville campaign—famed activists like John Lewis, Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, and more—played critical roles in the subsequent Black Freedom Struggle. A strong Nashville contingent remained instrumental to forming and guiding the early years of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), rescuing the Freedom Rides in 1961, and taking the Movement further into the heart of the segregationist South well into the 1960s. The story of nonviolence and lunch counters in Nashville, plus the formidable personalities who emerged from that struggle, drew a spotlight to the city even then. That vivid legacy has not dimmed today.

We amplify and enrich that legacy by pausing to examine Lawson’s stint in Nashville more closely. Indeed, the import of those years is only enhanced when we grapple with what Lawson endured and provoked at the time. His “time of testing” tells us much about the slow and uneven paths to justice for himself, and even more slowly for Nashville and the South.

This book centers on a few months in spring 1960 when Vanderbilt University expelled James Lawson because of the local lunch-counter demonstrations. As one person, “in a soft, sad voice,” summarized it at the time, “A person and an event came to symbolize a very great set of principles—freedom of action, freedom of conscience, the nature of a university, and in this case the struggle of the Negro for rights.” Typical accounts tracing Lawson’s career or treating Nashville’s civil rights history usually contain a paragraph or page about this expulsion. Lawson emerged as a featured target for segregationist rage even as the city still reeled from the protests. His ouster occurred even as the sit-in campaign remained ongoing and during Lawson’s final semester before graduating from Vanderbilt’s Divinity School. A groundswell of outcries from white academic and religious circles as well as the wider Movement empowered some of Lawson’s professors to support him publicly, eventually by resigning from the university.

That journey brought [James Lawson] to Nashville. It is not hackneyed to understand his time there as an instance where one man shaped a particular historical moment profoundly. Lawson played an “incomparable” role in shaping Nashville’s singular place in civil rights history. He moved there already well-established as an activist, deeply interlinked with networks of people trying to instill nonviolence more widely in Black communities across America. In doing that same work in Nashville, he cultivated a small cadre of ministers and students from the city’s Black churches and universities. Under Lawson’s tutelage, these regular people decided to do something extraordinary. They consciously chose to embrace bodily harm so as to literally step and sit outside the normal patterns of racism that intruded upon their lives.

Helped by Lawson’s preparatory work, these students were ready to act in 1960 when sit-ins shook the South in protest against the prevailing lunch-counter discrimination common to the era. Nashville’s demonstrations were distinguished for exhibiting on a substantial scale an unusually disciplined and sophisticated form of nonviolent resistance. This sustained commitment eventually made Nashville the first major Southern city to desegregate its lunch counters. Equally importantly, many of those forged with nonviolent steel by Lawson during the Nashville campaign—famed activists like John Lewis, Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, and more—played critical roles in the subsequent Black Freedom Struggle. A strong Nashville contingent remained instrumental to forming and guiding the early years of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), rescuing the Freedom Rides in 1961, and taking the Movement further into the heart of the segregationist South well into the 1960s. The story of nonviolence and lunch counters in Nashville, plus the formidable personalities who emerged from that struggle, drew a spotlight to the city even then. That vivid legacy has not dimmed today.

We amplify and enrich that legacy by pausing to examine Lawson’s stint in Nashville more closely. Indeed, the import of those years is only enhanced when we grapple with what Lawson endured and provoked at the time. His “time of testing” tells us much about the slow and uneven paths to justice for himself, and even more slowly for Nashville and the South.

This book centers on a few months in spring 1960 when Vanderbilt University expelled James Lawson because of the local lunch-counter demonstrations. As one person, “in a soft, sad voice,” summarized it at the time, “A person and an event came to symbolize a very great set of principles—freedom of action, freedom of conscience, the nature of a university, and in this case the struggle of the Negro for rights.” Typical accounts tracing Lawson’s career or treating Nashville’s civil rights history usually contain a paragraph or page about this expulsion. Lawson emerged as a featured target for segregationist rage even as the city still reeled from the protests. His ouster occurred even as the sit-in campaign remained ongoing and during Lawson’s final semester before graduating from Vanderbilt’s Divinity School. A groundswell of outcries from white academic and religious circles as well as the wider Movement empowered some of Lawson’s professors to support him publicly, eventually by resigning from the university.

Cuprins

Introduction

Chapter One: The Call to Nashville

Chapter Two: Reckonings

Chapter Three: Endgames and Legacies

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Chapter One: The Call to Nashville

Chapter Two: Reckonings

Chapter Three: Endgames and Legacies

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Descriere

The widespread controversy that rocked Nashville in 1960 after a famous civil rights leader was expelled from Vanderbilt University Divinity School