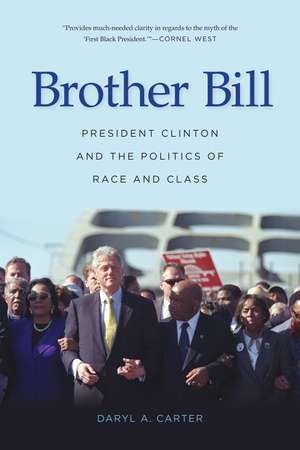

Brother Bill: President Clinton and the Politics of Race and Class

Autor Daryl A Carteren Limba Engleză Paperback – iun 2016

“This book is a fascinating analysis of race and class in the age of President Bill Clinton. It provides much-needed clarity in regards to the myth of the ‘First Black President.’ It contributes much to our understanding of the history that informs our present moment!”

—Cornel West

As President Barack Obama was sworn into office on January 20, 2009, the United States was abuzz with talk of the first African American president. At this historic moment, one man standing on the inaugural platform, seemingly a relic of the past, had actually been called by the moniker the “first black president” for years.

President William Jefferson Clinton had long enjoyed the support of African Americans during his political career, but the man from Hope also had a complex and tenuous relationship with this faction of his political base. Clinton stood at the nexus of intense political battles between conservatives’ demands for a return to the past and African Americans’ demands for change and fuller equality. He also struggled with the class dynamics dividing the American electorate, especially African Americans. Those with financial means seized newfound opportunities to go to college, enter the professions, pursue entrepreneurial ambitions, and engage in mainstream politics, while those without financial means were essentially left behind. The former became key to Clinton’s political success as he skillfully negotiated the African American class structure while at the same time maintaining the support of white Americans. The results were tremendously positive for some African Americans. For others, the Clinton presidency was devastating.

Brother Bill examines President Clinton’s political relationship with African Americans and illuminates the nuances of race and class at the end of the twentieth century, an era of technological, political, and social upheaval.

—Cornel West

As President Barack Obama was sworn into office on January 20, 2009, the United States was abuzz with talk of the first African American president. At this historic moment, one man standing on the inaugural platform, seemingly a relic of the past, had actually been called by the moniker the “first black president” for years.

President William Jefferson Clinton had long enjoyed the support of African Americans during his political career, but the man from Hope also had a complex and tenuous relationship with this faction of his political base. Clinton stood at the nexus of intense political battles between conservatives’ demands for a return to the past and African Americans’ demands for change and fuller equality. He also struggled with the class dynamics dividing the American electorate, especially African Americans. Those with financial means seized newfound opportunities to go to college, enter the professions, pursue entrepreneurial ambitions, and engage in mainstream politics, while those without financial means were essentially left behind. The former became key to Clinton’s political success as he skillfully negotiated the African American class structure while at the same time maintaining the support of white Americans. The results were tremendously positive for some African Americans. For others, the Clinton presidency was devastating.

Brother Bill examines President Clinton’s political relationship with African Americans and illuminates the nuances of race and class at the end of the twentieth century, an era of technological, political, and social upheaval.

Preț: 211.07 lei

Preț vechi: 313.56 lei

-33%

Puncte Express: 317

Preț estimativ în valută:

37.31€ • 44.35$ • 32.38£

37.31€ • 44.35$ • 32.38£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781557286994

ISBN-10: 155728699X

Pagini: 300

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.51 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Arkansas Press

Colecția University of Arkansas Press

ISBN-10: 155728699X

Pagini: 300

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.51 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Arkansas Press

Colecția University of Arkansas Press

Recenzii

“This book is a fascinating analysis of race and class in the age of President Bill Clinton. It provides much-needed clarity in regards to the myth of the ‘First Black President.’ It contributes much to our understanding of the history that informs our present moment!”

—Cornel West

—Cornel West

“Race had everything to do with the steady rise of the Republican Party after the 1964 election, and during Clinton’s remaking of the Democratic Party he often tweaked the party’s positions in a direction meant to bring white voters back into the fold. Daryl Carter’s Brother Bill is a long, patient recitation of these efforts. … Carter writes in a deliberately measured, even sweet-natured voice that puts his account at a far remove tonally from, say, Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow or Ava DuVernay’s documentary film 13th. He gives Clinton credit for saving affirmative action at a time when it was under severe attack, as it isn’t now. He reminds us that the crime and welfare bills Clinton signed had strong black support in polls at the time and that many black members of Congress voted for both; today, black voters, especially younger ones, are far more critical of these measures.”

—Nicholas Lemann, The New York Review of Books, June 2017

—Nicholas Lemann, The New York Review of Books, June 2017

“In Brother Bill, historian Daryl A. Carter digs deep into the hot-button racial issues of the 1990s to interrogate popular conceptions of Bill Clinton as the first “black” president. Not surprisingly, Carter unearths a complicated relationship between African Americans and the Clinton agenda. Class, rather than race, motivated many of the president’s actions. Eager to maintain support from white moderates, Clinton promoted policies that benefited the middle class—including the growing black middle class—while ignoring or even harming the African American underclass. … Carter demonstrates a solid grasp of his subject matter and has made good use of an array of primary and secondary sources ranging from government reports to contemporary news articles to recent historical and sociological writings. A handful of oral histories lend his discussion a personal flair. His insistence that historians of recent America must do a better job of untangling the complex interplay between class and race is a highlight of Brother Bill.”

—David Welky, H-Net FedHist, June 2017

—David Welky, H-Net FedHist, June 2017

“Daryl Carter’s Brother Bill is the place to begin if you want to understand why a president whose signature domestic reforms devastated inner-city black neighborhoods continues to be immensely popular among African Americans. His thesis—that Clinton’s popularity rests largely on his close ties to a black elite that has increasingly distanced itself from poor and working-class African Americans—is bound to be controversial, but no one interested in recent American history can ignore this important and insightful book.”

—Michael Pierce, Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Spring 2017

—Michael Pierce, Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Spring 2017

“[Carter] offers scholars of both U.S. and black politics new insights that challenge contemporary narratives about race and politics in twenty-first-century America. … this is an important book. As an opening salvo of historical analysis of the Clinton years, Carter has done an admirable job.”

—Joshua D. Farrington, The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Winter 2018

—Joshua D. Farrington, The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Winter 2018

“Overall, Brother Bill is an extremely well-written and documented book that uses a solid combination of primary and secondary sources. The book addresses Carter’s goals to dispel the myth of a monolithic black community and show the sophisticated and rapidly changing ideas in America, while making sense of the often-perplexing Clinton presidency and his most loyal constituency, the African American community.”

—Henry T. Brownlee Jr., The Journal of African American History, September 2019

Notă biografică

Daryl A. Carter is associate professor of history at East Tennessee State University. He specializes in modern American political history and African American history.

Extras

From Chapter 4

Responsibility and Accountability

The Politics of Crime

In 1981, Rickey Ray Rector, a poor black man from Conway, Arkansas, murdered a man at a dance. Following days of searching for the widely acknowledged dim-witted man, Rector’s sister called the Conway Police Department to report that her brother wanted to turn himself in. Officer Robert Martin entered the home of Rector’s mother, where he was staying, and talked casually with Mrs. Rector. Suddenly Rector walked into the room. Martin noticed him and asked him how he was doing. When Rector said, “Hi, Mr. Bob,” Martin returned to his conversation. Without warning or provocation, Rector shot the officer.

Officer Martin was mortally wounded. Rector ran out of the back of the house into the yard. Perhaps realizing for the first time what he had done, or resigned that he might be murdered himself, or perhaps fearful of returning to prison, Rector took the loaded firearm, pointed it to his head, and fired. The resulting wound was nearly fatal. Emergency room physicians and nurses in Little Rock worked to save the cop killer. They were successful. But in order to save his life the doctors had to remove three inches of brain tissue, from the forehead to nearly the middle of his head. Effectively, Rector had given himself a crude frontal lobotomy. What Rector did not take care of, the doctors did. He was left with the capacity of a five- to seven-year-old. Subsequently, Rector was declared competent to stand trial by a white Arkansas judge and convicted by an all-white jury. The sentence: death.

For years, Rector went through the long, winding road of appeals with no results. But in 1992, Governor Bill Clinton needed to demonstrate his toughness on crime. Despite the pleas from doctors, civil rights groups, and Rector’s attorneys, Clinton refused to budge. Clinton even flew back to Little Rock from New Hampshire to oversee the last few days of Rector’s life. It is also noteworthy that this occurred at the same time that Clinton’s longtime paramour, Gennifer Flowers, was revealing their affair and the Clinton campaign was reeling. On January 24, 1992, Rector was put to death by lethal injection in Cummins, Arkansas. Many argued, then and later, that it was clear, given the circumstances, that Rector should have been given a stay of execution and his punishment reduced to life imprisonment. Even those who had examined Rector admitted to one degree or another that Rector was childlike and of questionable competence. Years later Clinton continued to maintain that the execution was legitimate. In an interview on National Public Radio with Amy Goodman on Election Day 2000, Clinton argued that Rector “was not mentally impaired when he committed the crime. He became mentally impaired because he was wounded after he murdered somebody. . . . Had he been mentally impaired when he committed, I would never have carried out the death penalty, because he was not in a position to know what he was doing. That is not what the facts were.”1 For Clinton this was a “value” issue: Rector murdered someone, a cop no less. The fact that Rector gravely injured himself after the fact did not absolve him from the crime of murdering a police office.

Clinton’s actions followed the New Democrat philosophy on crime: compassion for victims, tough on criminals. Rector’s alleged incompetence was not a factor in Clinton’s decision, since he was fully competent when the crime took place. That Clinton was willing to allow this execution to proceed, despite the widespread pleas coming in from across the nation, was a notice about the direction in which he would take the Democratic Party and the nation in the years to come.

The Rector case is a window through which Clinton can be understood. Older notions that argued environmental concerns helped dictate behavior—somewhat an article of faith among liberals—divided America between criminals and victims, thus tearing at the fabric of society and destroying the vision of community, opportunity, and responsibility that Clinton was advocating.

In 1994, Congress passed and President Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. The law implemented federal restrictions on assault weapons, increased penalties for domestic violence, and provided funding for crime prevention. The legislation also put more than a hundred thousand police officers on the streets, provided billions for new prisons, and expanded the federal death penalty. The tougher approach to the issue of crime resonated with white, middle-class Americans who were central to Clinton’s electoral coalition and his fight against stiff Republican opposition to his legislative agenda.

Many in the African American community, especially clergy and the middle and upper classes, were receptive to the new law and supported its passage. Blacks, statistically, were far more likely to be victims of crime, especially violent crime. Their support was illustrative of the class divisions within the African American community. The effects of the law continue to be felt a decade and a half after it was signed into law. President Clinton’s political skill in manipulating black class divisions through values-oriented rhetoric helped lead to the passage of this controversial piece of crime legislation. It had a disproportionate impact on the poor African Americans who were further stigmatized, harassed, and imprisoned by the new law and those chosen to enforce it.

Responsibility and Accountability

The Politics of Crime

In 1981, Rickey Ray Rector, a poor black man from Conway, Arkansas, murdered a man at a dance. Following days of searching for the widely acknowledged dim-witted man, Rector’s sister called the Conway Police Department to report that her brother wanted to turn himself in. Officer Robert Martin entered the home of Rector’s mother, where he was staying, and talked casually with Mrs. Rector. Suddenly Rector walked into the room. Martin noticed him and asked him how he was doing. When Rector said, “Hi, Mr. Bob,” Martin returned to his conversation. Without warning or provocation, Rector shot the officer.

Officer Martin was mortally wounded. Rector ran out of the back of the house into the yard. Perhaps realizing for the first time what he had done, or resigned that he might be murdered himself, or perhaps fearful of returning to prison, Rector took the loaded firearm, pointed it to his head, and fired. The resulting wound was nearly fatal. Emergency room physicians and nurses in Little Rock worked to save the cop killer. They were successful. But in order to save his life the doctors had to remove three inches of brain tissue, from the forehead to nearly the middle of his head. Effectively, Rector had given himself a crude frontal lobotomy. What Rector did not take care of, the doctors did. He was left with the capacity of a five- to seven-year-old. Subsequently, Rector was declared competent to stand trial by a white Arkansas judge and convicted by an all-white jury. The sentence: death.

For years, Rector went through the long, winding road of appeals with no results. But in 1992, Governor Bill Clinton needed to demonstrate his toughness on crime. Despite the pleas from doctors, civil rights groups, and Rector’s attorneys, Clinton refused to budge. Clinton even flew back to Little Rock from New Hampshire to oversee the last few days of Rector’s life. It is also noteworthy that this occurred at the same time that Clinton’s longtime paramour, Gennifer Flowers, was revealing their affair and the Clinton campaign was reeling. On January 24, 1992, Rector was put to death by lethal injection in Cummins, Arkansas. Many argued, then and later, that it was clear, given the circumstances, that Rector should have been given a stay of execution and his punishment reduced to life imprisonment. Even those who had examined Rector admitted to one degree or another that Rector was childlike and of questionable competence. Years later Clinton continued to maintain that the execution was legitimate. In an interview on National Public Radio with Amy Goodman on Election Day 2000, Clinton argued that Rector “was not mentally impaired when he committed the crime. He became mentally impaired because he was wounded after he murdered somebody. . . . Had he been mentally impaired when he committed, I would never have carried out the death penalty, because he was not in a position to know what he was doing. That is not what the facts were.”1 For Clinton this was a “value” issue: Rector murdered someone, a cop no less. The fact that Rector gravely injured himself after the fact did not absolve him from the crime of murdering a police office.

Clinton’s actions followed the New Democrat philosophy on crime: compassion for victims, tough on criminals. Rector’s alleged incompetence was not a factor in Clinton’s decision, since he was fully competent when the crime took place. That Clinton was willing to allow this execution to proceed, despite the widespread pleas coming in from across the nation, was a notice about the direction in which he would take the Democratic Party and the nation in the years to come.

The Rector case is a window through which Clinton can be understood. Older notions that argued environmental concerns helped dictate behavior—somewhat an article of faith among liberals—divided America between criminals and victims, thus tearing at the fabric of society and destroying the vision of community, opportunity, and responsibility that Clinton was advocating.

In 1994, Congress passed and President Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. The law implemented federal restrictions on assault weapons, increased penalties for domestic violence, and provided funding for crime prevention. The legislation also put more than a hundred thousand police officers on the streets, provided billions for new prisons, and expanded the federal death penalty. The tougher approach to the issue of crime resonated with white, middle-class Americans who were central to Clinton’s electoral coalition and his fight against stiff Republican opposition to his legislative agenda.

Many in the African American community, especially clergy and the middle and upper classes, were receptive to the new law and supported its passage. Blacks, statistically, were far more likely to be victims of crime, especially violent crime. Their support was illustrative of the class divisions within the African American community. The effects of the law continue to be felt a decade and a half after it was signed into law. President Clinton’s political skill in manipulating black class divisions through values-oriented rhetoric helped lead to the passage of this controversial piece of crime legislation. It had a disproportionate impact on the poor African Americans who were further stigmatized, harassed, and imprisoned by the new law and those chosen to enforce it.